The pictures mentioned in Hearing Secret Harmonies bring motifs from the preceding volumes full circle. Jenkins revisits Barnaby, Isbister, and the Duport Seascapes. Widmerpool gets his due with The Omnipresent and the Modigliani. The novel ends where it starts, with Poussin.

Isbister Paints St John Clarke

A television program celebrating the life of St. John Clarke starts and ends with “St. John Clarke’s portrait (butterfly collar, floppy bow tie) painted by his old friend, Horace Isbister, R.A.” [HSH 39/40 ].

Isbister, whom Powell introduced in QU, has a number of appearances in Dance [The Walpole-Wilson Portraits (BM), Isbister, The British Frans Hals (AW), At the Isbister Memorial Exhibition (AW), Isbister According to St. John Clarke (CCR), and Outside the Army Council Room (MP)] prior to HSH. Later in HSH, Jenkins mentions a final Isbister portrait, that of Sir Horrocks Rusby in wig and gown, presumably similar to the portrait of Lord Aberavon [HSH 62-3/65]

John Galsworthy

Rudolf Helmut Sauter, 1923

oil on canvas

University of Birmingham;

© the copyright holder. Photo credit: University of Birmingham

from ArtUK.org

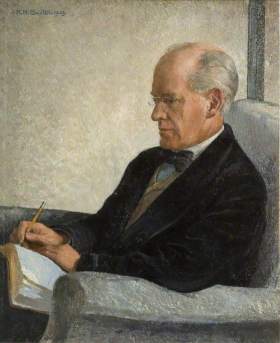

John Galsworthy is often mentioned as a model for Clarke, so we offer a portrait of Galsworthy, collar, bowtie , and all. Rudolf Sauter’s (1895-1977) biography does not match Isbister’s: Sauter showed at the Royal Academy but was never elected to membership; he was Galsworthy’s nephew and illustrated the definitive edition of his works. The portrait is worthy of Isbister, competently flattering the sitter, but leaving the viewer minimally informed and unexcited. Other portraits of Galsworthy with collar and bowtie, including those by William Strang R.A. (1859-1921) (lithograph), the caricaturist Sir David Low (1891-1963) (pencil), and various photographers shown at the National Portrait Gallery, do not provide other clues to models for Isbister.

After Jenkins and his friends watched the program, “Members then let off a mild bombshell. He suggested that the friendship with Isbister had been a homosexual one. The contention of Members was that the central figure in an early genre pictures of Isbister’s — Clergyman eating an Apple — was not at all unlike Clarke as a young man, Members advancing the theory that Isbister could have possessed a fetishist taste for male lovers dressed in ecclesiastical costume.” [HSH 40/]

Even with this new clue, we have not been able to find a facsimile of the Clergyman. Like Jenkins and his friends, we will leave Horace Isbister, R.A. still a subject for amused speculation.

Wyndham Lewis’ drawing of Sir Magnus Donners

Matilda kept a drawing of Sir Magnus Donners by Wyndham Lewis “resurrected in her sitting-room.” [HSH 49/50]

We already know that Sir Magnus collected works by British artists who were his contemporaries, like Sickert, Condor, John, and Steer. Percy Wyndham Lewis (1881-1957) was born in Canada but spent much of his artistic life in Britain. Like Sickert and John, he was an early member of the Camden Town Group (1911). Powell and Lewis had friends in common, like Constant Lambert, and Powell particularly admired some of Lewis’ novels, such as Tara (1918); however, they did not meet until the early 1950s. Powell described Lewis from that meeting:

“Big, toothy, awkward in manner, Lewis behaved with an uneasy mixture of nervousness and hauteur. In his white shirt and dark suit he looked like a caricature of an American senator or businessman,…” [TKBR 198]

Workshop

Wyndham Lewis, ~1914-15

oil on canvas, 31 x 24 in

The Tate Britain, London

from Tate Online via Wikimedia Commons

©The estate of Wyndham Lewis and the Estate of Mrs G Wyndham Lewis and the Estate of Mrs G A Wyndham Lewis

T. S. Eliot

Wyndham Lewis, 1938

Durban Municipal Art Gallery, South Africa

photo from National Portrait Gallery © The Estate of Mrs G.A. Wyndham Lewis: The Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust,

Lewis founded a style of geometrical abstraction, dubbed Vorticism, a descendant of Cubism and of Futurism, exemplified by Workshop (shown left.) After the First War, his work became more representational, and his portraiture, especially after 1930, gained renown. In 1932, Sickert called him “the greatest portraitist of this or any other time.” This view, however, was hardly universal. In 1938, the Royal Academy, still in the thrall of the likes of Isbister, rejected Lewis’ portrait of T.S. Eliot for an exhibition; Augustus John resigned from the R.A. in protest.

Recalling the similarities between Sir Magnus and Lord Beaverbrook, we have looked for a Lewis portrait of Beaverbrook and not found one; Beaverbook was, however, influential in Lewis’ appointment as a Canadian war artist, Lewis’ work hangs in the Beaverbrook Art Gallery.

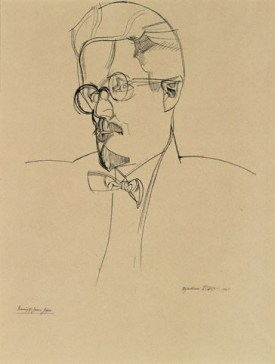

James Joyce

Wyndham Lewis, 1921

National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

photo from National Portrait Gallery

© The Estate of Mrs G.A. Wyndham Lewis: The Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust

Constant Lambert

after (Percy) Wyndham Lewis, 1932

Lithograph, 15 x 11 inches

National Portrait Gallery, London

© Wyndham Lewis and the estate of the late Mrs G A Wyndham Lewis; The Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust

Matilda owned a drawing rather than a painting, so perhaps a better approximation of her the portrait of Sir Magnus would be Lewis’ drawing of James Joyce. We also show a lithograph by Lewis of Constant Lambert to emphasize the relationships linking Powell and Lewis.

Aubrey Beardsley

“’I never pay my insurance policy, ‘ Moreland said, ‘without envisaging the documents going through the hands of Aubrey Beardsley and Kafka, before being laid on the desk of Wallace Stevens.’” [HSH 53 /54]

On June 24, 2015, Bonhams auctioneers sold a first edition of Lysistrata, illustrated by Aubrey Beardsley, from Anthony Powell’s library. They also auctioned an assorted set of other Beardsley pieces from Powell’s collection. Powell had inherited the Beardsley works from his father, who had “certain fin-de-siècle leanings. In one form, these were expressed by delight in the drawings of Aubrey Beardsley, though this attraction for the Décadence was balanced by disapproval of much that it stood for. [TKBR 15]” (For other items auctioned from Powell’s collection, see the Bonhams’ catalog, items 299-342.)

In his youth, Powell would study the drawings in his father’s books. When he was 17, his own black and white drawing, Caesar Cannonbrains of the Black Hussars, appeared in the Eton Candle; In TKBR (p. 55, drawing on p.56), Powell says the drawing shows unconcealed influences of Beardsley and Lovat Fraser. Later, Powell wrote four essays about Beardsley, anthologized in Under Review: Further Writing on Writers, 1946-1990 [pp 44-52].

Aubrey Vincent Beardsley (1872-1898) began work as a clerk for the Guardian Life and Fire Insurance Office at age 17. In 1891 he and his sister went to the studio of Edward Burne-Jones under the mistaken impression that it was open to visitors; Burne-Jones invited them in, some say because of Mabel Beardsley’s striking red hair, examined Beardsley sketches, and arranged for him to attend art classes at night, resulting in a few months at the Westminster School of Art, which were his only formal artistic training. The Beardsleys left Burne-Jones’ studio with Oscar Wilde, beginning an association that linked Beardsey with Wilde in the forefront of Aestheticism.

The Dancer’s Reward

Aubrey Beardsley, 1894

plate from Oscar Wilde’s Salome

photo from The Victorian Web

Wilde and Beardsley had a fraught relationship. For example, Wilde invited Beardsley to illustrate the English edition of his Salome. (Powell owned a first edition (1894).) Wilde, however, was unhappy with the illustrations, believing that they misrepresented and distracted from his writing.

Beardsley worked in black and white, using block prints. His sensual style, often highlighting the erotic, influenced Art Nouveau and the Arts and Crafts movement. Critics sometimes classed Beardsley as a Decadent; he dressed foppishly, enforcing this reputation, and delighted in the grotesque aspects of his image. Like a character from La Boheme (Puccini, 1896), he died young of tuberculosis.

We regret that our brief does not allow us to digress further to review the geniuses of Kafka and Stevens.

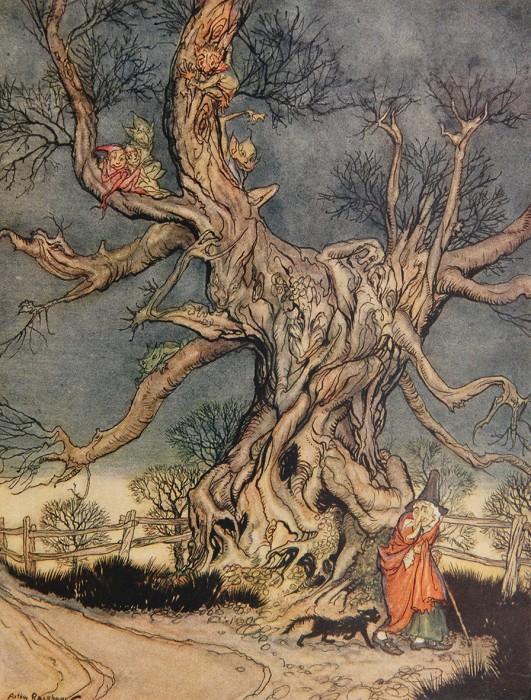

Tree Trunks from an Arthur Rackham Illustration

Near the Devil’s Fingers, Jenkins sees;

“The elder thicket was flowering, blossom like hoar frost, a faint sprinkling of browonish red, powdered over the green and white ivy-strangled tree-trunks, gnarled and twisted, as in an Arthur Rackham goblin-haunted illustration.” [HSH 150/ 161]

Colored plate from

Washington Irving The Legend of Sleepy Hollow

Arthur Rackham, illustrator, 1928

Geroge G. Harrap, publisher, London

photo from Laura Massey The Golden Age of Illustration: Arthur Rackham

Arthur Rackham (1867- 1939) was the preeminent children’s book illustrator of the early twentieth century. Like Beardsley, he began his career as an insurance clerk. One of the first books he illustrated was The Ingoldsby Legends (1898). He was a master of gnarled tree trunks, often inhabited by little people; we show just a couple of many possible examples.

Illustration from Midsummer Night’s Dream

Arthur Rackham, 1908

photo from Laura Massey The Golden Age of Illustration: Arthur Rackham

The list of classic works that Rackham illustrated is long, including Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm, Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, Wind in the Willows, and Alice in Wonderland, among many others.

The Whispering Knights

Talking about the Devil’s Fingers, Mr. Goldney, of the archeological society, says, “It’s an interesting little site. Not up to the The Whispering Knights, where I was last month. That’s an altogether grander affair. Still, we have to be grateful for what we have in our neighborhood.’

Jenkins asks, ” Why is it called The Whispering Knights? I’ve heard the name, but never been there.”

“During a battle some knights were standing apart, plotting against their king. A witch passed, and turned them into stone for their treachery.” [HSH 160/172]

The Whispering Knights

Neolithic portal dolmen

Great and Little Rollright, Oxfordshire

photo by Midnightblueowl by Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license via Wikimedia.org

The Devil’s Fingers is supposed to be one of the many stone monuments found throughout Britain. One example is The Whispering Knights, four upright stones and a fallen capstone, that mark a burial site in Oxfordshire. The Knights grave site is thought to have been placed five to six thousand years ago. Nearby are slightly newer Neolithic monuments, The King Stone and a circle of 77 stones known as The King’s Men.

Jenkins is visiting the Devil’s Fingers on the morning after Midsummer’s Eve, which was the classic time for pagan celebrations at sites like The Whispering Nights (Jacobs et al., “Devil’s Stones and Midnight Rites: Megaliths, Folklore, and Contemporary Pagan Witchcraft” Folklore 2014; 125:60-71) In the mid-twentieth century, Wiccan cults would meet at these stones for naked rituals to the Horned God, perhaps similar to the horned stag-mask dance that Gwinett saw Scorp Murtlock and his followers perform. [HSH 152-157/164-169].

A Portrait of Queen Elizabeth II

When Jenkins first visited Stourwater in the late 1920s, a portrait by Hans Holbein, famous for his portrait of King Henry VIII, hung in the long gallery. Now, when Jenkins returns to Stourwater for his nephew’s wedding in early 1971, he leaves the reception for a nostalgic wander around the castle. The tapestries of the seven deadly sins are gone and over the “fine chimneypiece, decorated with nymphs and satyrs – no doubt installed by Sir Magnus to harmonize with the tapestries” (HSH 191 [206]) is a copy of a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II by Annigoni.

Queen Elizabeth II, Queen Regent

Pietro Annigoni, 1955

Tempera, oil and ink on paper

The Fishmongers’ Hall. London

Copyright The Fishmonger’s Co.

photo from Wikipedia.org

Her Majesty in Robes of the British Empire

Pietro Annigoni, 1969

Tempera grassa on paper on panel. 79 x 71 in.

National Portrait Gallery, London.

Copyright The National Portrait Gallery

photo from Wikipedia.org

Pietro Annigoni (Italian,1910-1988) already had a successful career when he was commissioned by the Worshipful Company of Fishmongers to paint the Queen’s portrait in 1955. The idealized portrait of the young monarch was immensely popular. When it was displayed at the National Portrait Gallery in London the crowds were ten deep. The National Portrait Gallery commissioned Annigoni to do another portrait of the Queen Elizabeth in 1969.

After his 1955 portrait of Elizabeth, Annigoni was much in demand as a painter of the powerful — the Shah of Iran, Pope John XXIII, Presidents John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson; however, Annigoni was not always in agreement with the establishment. In 1970 he turned to graffiti, writings MURDERERS on the front of the National Gallery, to protest practices of painting restoration that he viewed as desecration.

We have not been able to find a facsimile of the chimneypiece, even though an apparently similar one was sold at auction by Christies in 1905. There are many portraits of Elizabeth that the new owners of Stourwater might have chosen to display over that mantel. We do not know if they chose the 1955 Annigoni, a thoughtful young monarch in a sylvan setting, or the 1969 version, gloomier and less popular. We would have preferred the lively Elizabeth of Gerhard Richter (1969). (The intense Elizabeth of Lucien Freud (2001) had not yet been painted.) In 1971, the satyrs and nymphs were still by the fireplace, but the sexual energy that Sir Magnus had brought to Stourwater was gone; the extravagant art was replaced with a reproduction, bland and official.

Barnaby Remembered

Barnby died, at age 39, in 1941 when his plane was shot down [SA 231/228], but Jenkins reminisces about him in HSH [ 191/206, 229 /247]. Wandering the passages of Stourwater, Jenkins passes through the room where Barnby’s portrait of the waitress from Casanova’s Chinese Restaurant had hung. One of the pictures in another room was also a Barnby, “an oil sketch of the model Conchita, described by Moreland as ‘antithesis of the pavement artist’s traditional representation of a loaf of bread, captioned Easy to Draw but Hard to Get.'” [HSH 191/206]

Reclining Female Nude

Adrian Daintrey

oil on canvas, 36 x 17 in.

listed at Invaluable.com

probably © the artist’s estate

Jenkins has told us of Barnby’s tastes but has given us few clues to the actual appearance of his pieces. Here with the mention of Conchita, we have another opportunity to make some guesses. Adrian Daintrey, oft cited as the model for Barnby, painted landscapes, cityscapes, still lives, and portraits. Despite the reputation as a womanizer that he shared with Barnby, he displayed few nudes; however, by diligent searching, we have discovered one (shown left). It shows his flair for bold swaths of color and prominent brush work. Her dark complexion and the exotic flower in her hair make her a plausible stand-in for La Conchita. Augustus John had also used Conchita as a model, but after reviewing a number of his nudes, we have not had the satisfaction of identifying Daintrey’s model among them.

Both Barnby and Daintrey were war artists during the Second War. Barnby’s painterly skills were soon applied to camouflage work, “disguising aerodromes as Tudor cottages,” [VB /18 ], which undoubtedly limited his palette of colors. Some of Daintrey’s war works, like French Soldiers at Sidon, 1944 and Egyptian Solders on a Truck, are now in the Imperial War Museum (digital images not available on the museum web site – accessed Dec. 4, 2016). Daintrey died in 1988.

The Omnipresent Recalled: On the Precipice

Jenkins encounters Widmerpool “more or less entangled” with Murtlock’s cult. “The spectacle of him wearing a blue robe was nevertheless a startling one. … The image immediately brought to mind was one not thought of for years; the picture, reproduced in colour, that used to hang in the flat Widmerpool shared with his mother in his early London days. It had been called The Omnipresent. Three blue robed figures respectively knelt, stood with bowed head, gazed heavenward with extended hands, all poised on the brink of a precipice. “ [HSH 197/213]

“It was a long time ago. I may have remembered it incorrectly. Nevertheless, it was these figures Widmerpool conjured up, as he advanced towards me.”

The Omnipresent

Baron Arild Rosencrantz

print, 25 x 18 in

offered on Denver Craig’s list, January, 2017

Of course, Jenkins describes the picture correctly, even though he had but glanced at the reproduction in the late 1920s. (Baron Arild Rosenkrantz had exhibited the original at the Royal Academy in 1907. The coloring of the reproduction that we show above suggests that it may have been from a run of half-tone prints made in 1932.)

The key words here are ‘conjured’ and ‘precipice.’ ‘Conjured’ because Murtlock’s cult is the culmination of magical, religious, and spiritual themes that haunt Dance from early in AW, first when Mrs. Erdleigh tells fortunes for Nick and his Uncle Giles, and subsequently in Dr. Trewalney’s and Mrs Erdleigh’s recurrent appearances. Powell recounts this spiritualism with barely suppressed amusement and shows that during the decades of the Dance, many cultured Britons dabbled in esotoric philosophies like Theosophy. For example, General Conyers, well connected to the Establishment, had interests ranging from psychoanalysis to the occult ideas of Dr. Trewalney. Rosenkrantz was a devotee of Rudolf Steiner, who developed Anthrosophy as an alternative to Theosophy.

The only previous mention of this picture is at the end of BM, when Nick glances it briefly in Widmerpool’s flat. Now, in retrospect, that glance could be read as foreshadowing the importance of the occult in the novel, just as the ‘precipice’ now foreshadows Widmerpool’s dramatic final scenes.

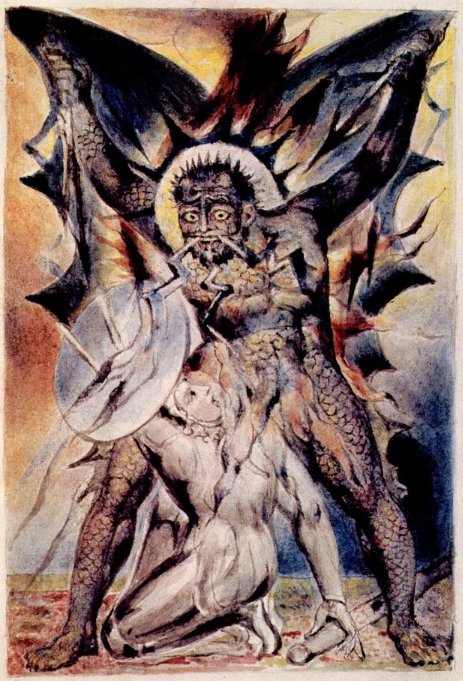

Apollyon, The Fiend Illustrated

Watching Murtlock approach alone, Jenkins recalls a childhood memory that he shared with Moreland, a fear that a lone approaching figure was Apollyon, the fiend from The Pilgrim’s Progress; “a lively portrayal of the fiend in an illustration, realistically depicting his goat’s horns, bat’s wings, lion’s claws, lizard’s legs — the terror of that image, bursting out from an otherwise at moments prosy narrative, had imbedded itself for all time in the [Moreland’s] imagination. ” [HSH 216/233 ]

John Bunyan published the allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress in 1677. It has remained in print since then, appearing in multiple editions with many different illustrators, and is still widely read as a Christian lesson. Apollyon, the Destroyer, is the rebel angel who battles the hero Christian. Our narrator is a bit unreliable; Jenkins and Mortland’s memory does not quite match Bunyan’s description:

The Christian Fights Apollyon

The Pilgrim’s Progress, Plate 20

William Blake, 1824-1827

Watercolor

The Frick Collection

from Dark Figures in the Desired Country: Blake’s Illustrations to The Pilgrim’s … By Gerda S. Norvig, The Google Book project via Wikimedia Commons

We are not sure which illustration Jenkins and Moreland remembered from their childhoods. The illustration by William Blake (1824-1827) shows the terrifying Apollyon in frightening detail, with the scales worthy of pride, but Blake’s originals were watercolors and were not published with a text of the Pilgrim’s progress at the time (Norvig, 1993). The are currently in the Frick Collection, which exhibits them intermittently.

A number of Victorian illustrators took on the subject. H.C. Selous and M. Paolo Priolo’s version won a prize competition from the London Art Union but does not quite convey the full force of the terror that would stay in boys’ memories for the rest of their lives (for contemporary reaction, see The Spectator, 13 January 1844 ).

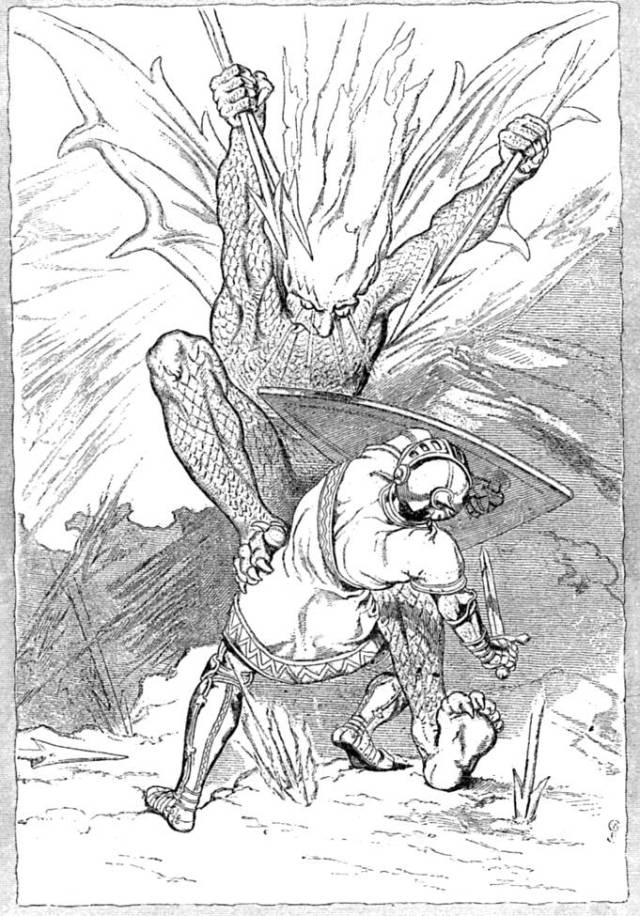

The Fight with Apollyon

Bunyan, John. The Pilgrim’s Progress . London, Edinburgh, and New York: Thomas Nelson and sons, 1887.

William Bell Scott

Wood block, 4 3/4 x 3 3/16 inches

image from the Victorian Web, scanned by George P. Landow

The illustration by William Bell Scott , published in 1887, catches Apollyon’s dynamic force, with plenty of claw and wing, but where are the horns?

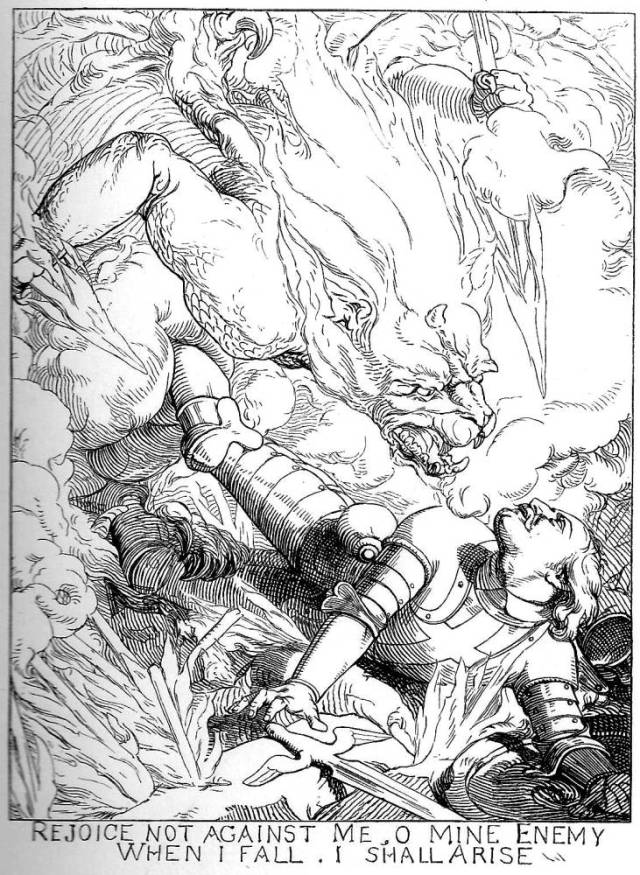

Christian Cast Down by Apollyon

from Illustrations to Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. London: Simpkin Marshall, 1864

Frederick Shields, 1864

Wood engraving, unsigned but probably by Joseph Swain,

4¾ x 4½ inches

from The Victorian Web, image scanned by Simon Cooke

The version by Frederick Shields shows Apollyon’s frightening fanged face but just a bit of claw and no wing to match Jenkins’ remembrance. There are many other Apollyons to consider, and new ones continue to appear, like an Apollyon in digital stained glass (Howard, 2014-2015). Perhaps imperfect memory, whether Powell’s, Jenkins’, or Mortland’s, inevitably prevents us from finding the exact fiend illustration that the boys recall; we suspect that like so many of Powell’s verbal images, the artwork that he describes is an olio of many works, mixed by his imagination.

Edgar Bosworth Deacon: Edwardian Symbolist

In a pile of old newspapers, about to be burned, Jenkins spies a review of the Bosworth Deacon Centenary Exhibition being mounted at the Barnabas Henderson Gallery.

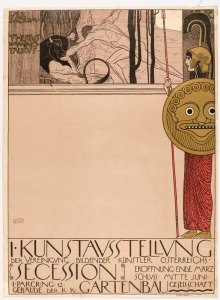

‘… albeit his roots lie in Continental Symbolism, Deacon’s art remains unique in itself. In certain moods he can recall Fernand Khnopff or Max Klinger, the Belgian’s near photographic technique observable in Deacon’s semi-naturalistic treatment of more than one of his favourite renderings of Greek and Roman legend. In his genre pictures, the academic compliances of the Secession School of Vienna are given strong homosexual bias…’ [HSH 226/247]

Poster for Secession I

Gustav Klimt, 1898

color lithograph, 39 x 28 in

Museum of Modern Art, NY

photo from nyarc.org

The Secession School of Vienna was a group of some 20 artists who seceded from the establishment Vienna Künstlerhaus in 1897. Their president and now best known member was Gustav Klimt (Austrian, 1862-1918). The Secessionists worked in multiple media and produced exhibitions, catalogues, and a magazine showing their views on the how art should respond to the new century. In the poster (at left) for their first exhibition, Athena, in red, symbolizes wisdom, and Theseus on the frieze above is batttling against philistinism. The poster was initially censored until Klimt added the tree to hide Theseus’ genitalia.

Fernand Khnopff (Belgian, 1858-1921) was an honorary member of the Secession. He displayed 21 works at the first Secession Exhibition in 1898.

I Lock My Door Upon Myself

Fernand Khnopff, 1891

oil on canvas

Neue Pinakothek, Munich

photo by Yelkrokoyade via Wikimedia Commons

We show I Lock My Door Upon Myself, which shows Khnopff’s debt to the Pre- Raphaelites. He made frequent trips to Britain and was friendly with artists like Hunt, Watts, Burne-Jones, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The painting is based on a poem by Christina Rossetti, sister of Dante Gabriel. The third stanza of the poem is

I lock the door upon myself,

And bar them out; but who shall wall

Self from myself, most loathed of all.

Khnopff was a Symbolist, who expected us to see the painting not as simple representation but as a narrative pieced together from its icons, like the dried red lilies. The white bust, which might have appealed to Mr. Deacon’s classical leanings, is of Hypnos, the god of sleep. For more on this painting and its iconography, watch the Khan Academy video on it.

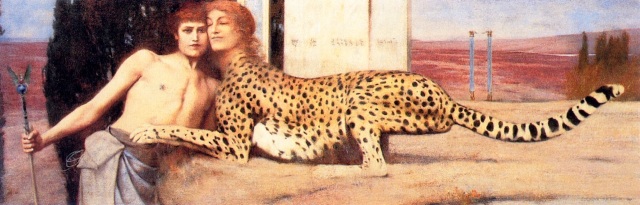

The Sphinx or The Caress

Fernand Khnopff, 1896

oil on canvas, 20 x 59 in

Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels

The Yorck Project via Wikimedia Commons

Jenkins read on in the review: “even Deacon’s sphinxes and chimeras posssessing solely male atrributes.” [HSH 226/247 ] Mr. Deacon would have liked Oedipus (left in The Caress), reminiscent of the androgynous figures in works by Mr. Deacon’s ‘master’, Simeon Solomon, but might not have approved any hint of the feminine in the face of Khnopff’s sphinx. Beethoven (shown below) by Max Klinger (German, 1857-1920 ), bare chested in a classical setting, would also likely get Mr. Deacon’s approval.

Beethoven

Max Klinger, 1902

marble, alabaster, amber, bronze, ivory; lifesize

Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig

photo by Henning Høholt from Kulturkompasset.com.

Klinger was another honorary member of the Secession. His Beethoven was the center piece of the fourteenth Secession Exhibition (1902), along with a frieze by Klimt. Klinger, like Khnopff, was a Symbolist. Some viewers see the eagle at Beethoven’s feet as an icon for Zeus, indicating that Beethoven is enthroned with the Olympian gods, or while others see the eagle as a symbol for Saint John the Baptist. The Secessionists believed in “spatial” art, so the whole exhibit room was designed as a temple to the deity in the sculpture, but some critics saw only an angry old man, waiting for his turn at a public bath.

Jenkins introduced Mr. Deacon at the beginning of A Buyer’s Market and mixed a fond nostalgia for Deacon with an ironic mockery of his theory and execution of art. Now that the reviewer compared Deacon to better known Symbolists and Secessionists, Jenkins felt “a sense of satisfaction in reading praise of Mr. Deacon… given by a responsible art critic” but was still quite aware of his shortcomings and marvelled that Deacon’s art was having “not so much a Resurrection as a Second Coming.” [HSH 227/248]

The Duport Collection

Henderson tells Jenkins: “Far the best of the Victorian marine painters show come from the Duport collection.” [HSH 233/252] Of course, Jenkins had seen these paintings years before and disdained them. Now we have a few more clues to their appearance. The newspaper review of the exhibition had praised the ‘virtuosity’ and ‘tightness of finish’ of Gannets Nesting, The Needles: Schooner Aground, and Angry Seas at Land’s End. [HSH 227/246]

Australian Gannet

John Gould, 1840-1848

hand colored lithograph from Birds of Australia,

Vol. 7 (n1-a.7): plate 76

Image from Glasgow University Special Collections Department

John Gould (1804-1881), like his contemporary James Audubon, was a skilled illustrator of birds. He published eight folios of Birds of Australia and many other folios of birds from all over the world, containing over 3000 color plates of birds. His work would merit the critic’s praise of virtuosity and finish.

The Clipper Ship “Flying Cloud” off the Needles, Isle of Wight

John Buttersworth, 1859-1860.

oil on panel, 12 x 18 in

Memorial Art Gallery, U. of Rochester, N.Y

photo in public domain from Wikipedia.org

The Needles are chalk stacks off the Isle of Wight, which are part of a chalk ridge running to Dorset. They have been the sight of many shipwrecks. This picture (left) of the wreck of the Irex, which occurred on January 25,1890, shows The Needles in a diagonal line pointing toward the horizon. We have been unable to identify the artist. A better known painting of The Needles is The Clipper Ship “Flying Cloud” by James Butterworth. The Flying Cloud held the record for the fastest passage under sail from New York to San Francisco and itself went aground off New Brunswick in 1874. Butterworth (1817-1894) was British but specialized in portraits of American ships. Our first reaction was that with Butterworth’s skill for detail and drama, his work could not have been in the Duport collection, but we became less certain of our opinion, when we read that Jenkins revised his prior

Boats near the Shore of Normandy

Richard Parkes Bonington, 1823-24

ol on canvas, 13 x 18 in

The Hermitage

view of the seascape: “The Needles: Schooner Aground was by no means without merit. The painter had evidently seen the work of Bonington.” [HSH 238/257]. Richard Parkes Bonington (Britsh 1802-1828) was a romantic landscape and seascape painter. He won a gold medal, as did John Constable, at the Paris Salon on 1824. So in the end, Jenkins admits that for all his sarcasm and fussiness about some works, he joins those who reassess work as time passes and tastes change.

The Longships Lighthouse, Land’s End, from the North-East

Joseph Mallord William Turner, ~1834

watercolor on white wove paper, 11 x 17 in

The Tate, London

Jenkins “was less keen on Angry Seas off Land’s End.” [HSH 238/257], so perhaps the rendition of that subject in the Duport Collection was not so masterly as this J. M. W. Turner vision of the powerful waves off Land’s End.

One of Goya’s Sad Duchesses

After many years in South America, Jean Duport reappears in London at the centenary exhibition of Mr. Deacon’s paintings. As she enters the gallery, Henderson remarks of Jean, “She looks like one of those sad Goya duchesses.” Later, Jenkins reflects, “Henderson was right about Jean. The metamorphosis, begun when the late Colonel Flores had been his country’s military attaché in London at the end of the war, was complete. She was now altogether transformed into a foreign lady of distinction.” [HSH 233/252]

This is to be Nick’s last glimpse of Jean Duport, whose austere beauty and sexual fascination have long haunted him. We first spied Jean in Question of Upbringing, when her mystery combined the appeal of a virginal saint and mysterious temptress [QU /75]. In Buyers’ Market Jean’s looks were compared to those of Rubens’ first and second wives, at once shy and alluring and confident and voluptuous [BM 226/216]. Then, in Acceptance World, the Romanticism of Delacroix’s hookah-smoking harem woman was invoked to add a note of exoticism to Jean’s allure [AW /58]. Later in Acceptance World Nick returns to the theme of medieval austerity to describe Jean’s beauty: “Her forehead, high and white, gave a withdrawn look, like a lady in a mediaeval triptych or carving … ” [AW 141/]. Here we could not help but be reminded of the Rogier van der Weyden (Netherlandish 1399-1464) portrait of a lady in the National Gallery in Washington D.C.

Portrait of a Lady

Rogier van der Weyden, ~1460

oil on panel, 13 x 10 in

National Gallery of Art, Washington

photo in public domain from the Google Art Project via Wikimedia Commons

For the carved version of the medieval lady, we propose the Mary Magdalene shown below, which may have originally stood in the Church of the Dominicans in Augsburg, Germany. Jenkins returns to Jean as a medieval image when he learns that she slept with Jimmy Brent during his own affair with her. “I thought of that grave gothic beauty that I had once loved so much, …. I thought her men are gothic too, being carved on the niches and corbels of a mediaeval cathedral….” [KO 183] We envision Mary Magdalene, dancing on a corbel above gargoyles who caricature the three unhappy lovers — Stripling, Jenkins, and Brent.

Saint Mary Magdalene

Gregor Erhart, 1515-1520

lime tree wood, polychrome, 71 x 18 x 17 in

Louvre Museum

© Musée de Louvre, 2011, Thierry Ollivier

Devils drag a sinner off to hell. Corbel at Notre Dame cathedral,Noyon, France

photo from London Stone Carving

on Twitter

@londoncarving

This is also our final recourse to Francisco Goya (Spanish 1746-1828), whose multi-faceted career we have considered twice earlier in Dance: in Buyers’s Market as a painter of a scandalous nude, and in Cassanova’s Chinese Restaurant as a Romantic chonicler of the life of the peasantry. There is also the Goya of the Spanish royal court, official painter of its noble family, the Goya who became a scathing political and social satirist, and finally a misanthrope of overwhelming visual rage. But long before the tragic final act of Goya’s career, he maintained a thriving practice as a portraitist to an aristocratic clientele that valued his special gifts in that genre. Those gifts included a delightful delicacy of touch and facility with likeness, but the flattery of his portraits consisted not so much in the prettifying of his subjects as in his ability to suggest a sympathy for their simple humanity, regardless of their wealth and station.

The Duchess of Alba

Francisco Goya, 1797

oil on canvas, 83 x 59 in

Hispanic Society of America

photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons

We show Goya’s 1797 portrait of the Duchess of Alba dressed in black, often called The Black Duchess, as an example of one of his “sad duchesses.” Powell’s allusion to Goya here is especially appropriate to Nick’s regard for Jean, as, historically, rumors have circulated that Goya’s regard for the duchess was romantic, even if research suggests an unrequited love, at most. Though still in the prime of her maturity, the duchess mourns the loss of her husband, just as Jean Duport has lost her Colonel Flores. Still, Goya’s duchess betrays less sadness than a kind of bewildered isolation, and an indignant refusal to accept her condition. As from the start, Nick’s fascination with Jean Duport lies not in any conventional beauty but in something else that she is for him, now described as “a foreign lady of distinction.”

Pop Art Armchairs

Powell mentions the chairs three times, so they caught our attention. In Barnabas Henderson’s art gallery, Jenkins sits down in the small cluttered basement office. “I chose an armchair of somewhat exotic design of which there were two [HSH 238-239/257].” Soon Bithel arrived and “deposited in the other exotic armchair [HSH 244/263].” Then, a few pages later, the punch line: “Bithel lay back, so far as doing so were possible, in the pop-art armchair. [HSH 248/267].” There is actually a fourth mention a couple of pages on.

Henderson, who monetizes old paintings and cares nothing for their history or aesthetics, furnishes his private space with the latest kitsch. Pop Art evolved in the 1950s and 1960s not only with the work of Americans like Andy Warhol, Roy Lichenstein, Claes Oldenburg, and James Rosenquist but also with a British contingent, drawing images from and contributing images to popular culture.

Chair

Allen Jones, 1969

Acrylic on glass fibre and resin with perspex and leather, 31 × 23 × 39 in

The Tate

© Allen Jones

The “arm” chair at left by Allen Jones, a British Pop artist, has its limbs in nontraditional locations, but we show it as our first example because it illustrates the debt of Pop Art to Dada and Surrealism. In the 1950s some of the pioneers of Pop, like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, were called Neo-Dadists. Powell (1971) wrote about the connection in one his reviews, seeing the Surrealist Magritte, in particular, as a forefather of Pop.

We examined many Pop Art chairs; see, for examples, 15 Most Bonkers Chairs at Pop Art Design in London. Our nomination for Henderson’s chair is the Up 5 Lounge Chair by Gaetano Pesce in classic Pop Art red. Pesce described the chair as “a female figure tied to a ball shaped ottoman symbolizing the shackles that keep women subjugated.”

Up 5 Lounge Chair with Up 6 Ottoman

Gaetano Pesce, 1969

Polyurethane foam covered in stretch fabric, 40 x 44 x 45 in; ottoman diameter 23 “

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2016 Gaetano Pesce

The Pop artists successfully blurred the distinction between kitsch and high art. Now, Pop is a museum staple. In 2013-4 the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Copenhagen, the Barbican in London, the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, and the Vitra Design Museum in Weil Am Rhein, Germany collaborated on an exhibit called Pop Art Design. If Barnabas Henderson were alive today, he would dust off those chairs, bring them up from the basement, and try to sell them for a pretty penny. We recently saw a yellow version of Pesce’s Up 5 Lounge Chair, somewhat worse for wear, offered on 1stdibs for $4223 (accessed 12/16/2016).

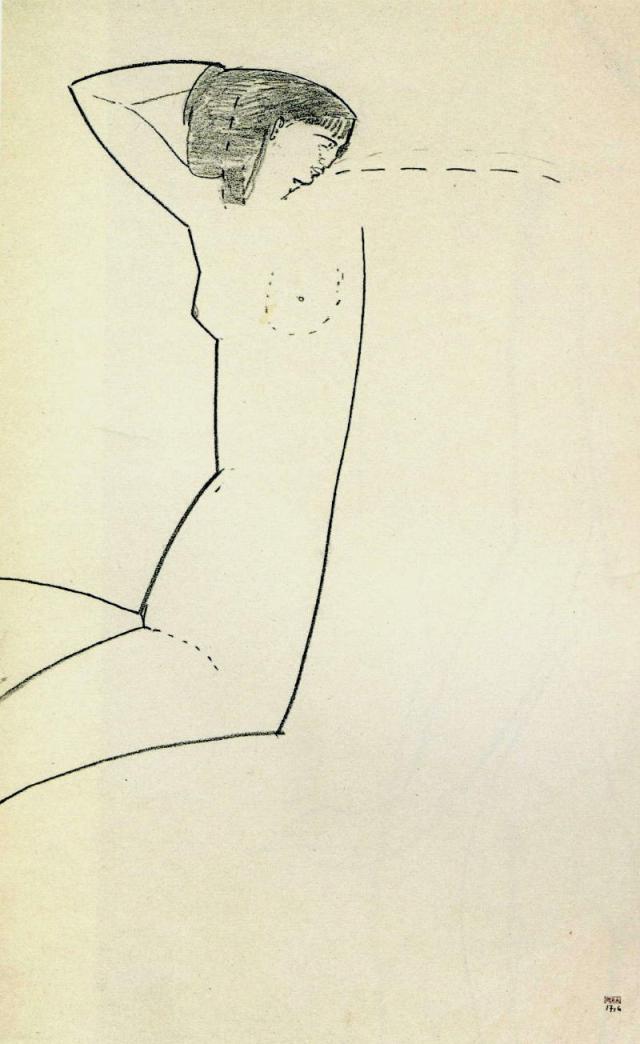

The Modigliani Reappears

Widmerpool’s unease with the artistic throughout Dance is bracketed by angular drawings, first his mocking pictograph in the cabinet de toilette at La Grenadière and now at the end of the novel by reappearance of the Modigliani drawing.

On the penultimate pages of HSH, Henderson unwraps the drawing, which has moved from Stringham’s possession to Pamela Flitton’s to Widmerpool’s, intertwined with Widmerpool’s rise and fall.

“The glass of the frame was cracked in several places; the elongated nude no worse than a little crumbled. It had been executed with a few strokes running diagonally across the paper. The marvellous economy of line would help in making it hard to identify — if anybody bothered — as more than a Modigliani drawing of its own particular period.” [HSH 250 ]

Anna

Amedeo Modigliani, 1911

black crayon 16 3/4 x 10 3/8 in

from ‘The Unknown Modigliani’ by Noël Alexandre

reproduced at richardnathanson.co.uk

We have previously shown some Modigliani drawings, but the additional description here suggests that Powell was thinking of the most simply drawn of Modigliani’s likenesses of Anna Ahkmatova. With a few lines, he reduced her beauty to its essential features. Perhaps Powell is drawing our attention to the stark contrast between Modigliani’s passionate relationship to the great Russian poet and Widmerpool’s difficult relationship to Flitton; yet there is similarity in that both women were objects of obsession.

Valedictory

“The smell from my bonfire, its smoke perhaps fusing with one of the quarry’s metallic odours drifting down through the silvery fog, now brought back that of the workmen’s bucket of glowing coke, burning outside their shelter.” [HSH 251/271] Powell’s magisterial and melancholy conclusion to Hearing Secret Harmonies, and the entire Dance, returns us to Powell’s beloved Nicolas Poussin, whose painting was evoked by the workmen’s bucket of glowing coke on the first page of A Question of Upbringing.

A Dance to the Music of Time

Nicolas Poussin, 1634-1636

oil on canvas, 33 x 42 in

The Wallace Collection, London

photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons

The very structure of Dance has echoed Poussin’s vision of the endless round of men’s fortunes, and brings to Nick’s mind “one of Robert Burton’s torrential passages from The Anatomy of Melancholy.” It is that litany of calamities that beset the lives of men, plus Powell’s reversion to the cadence of classicism, that encourage us to think of another of Poussin’s paintings as a valedictory image, even though it is not mentioned by Jenkins. Much later in his life than A Dance to the Music of Time, Poussin undertook a series of four canvases, now in the Louvre, to depict the seasons individually. Spring, Summer and even Autumn are filled with promises of plenty, but Winter (c.1660-4) is a vision of devastation and despair.

Winter (also called The Flood)

Nicolas Poussin, ~1660-1664

oil on canvas, 47 x 63 in

The Louvre

color adjusted photo public domain from the Yorck Project via Wikimedia Commons

Though the decades of Nick’s witness are filled with comic moments, it is the spirit of Burton’s melancholy that remains: “The thudding sound from the quarry had declined now to no more than a gentle reverberation, infinitely remote. It ceased altogether at the long drawn wail of a hooter—the distant pounding of centaurs’ hoofs dying away, as the last note of their conch trumpeted out over hyperborean seas. Even the formal measure of the Seasons seemed suspended in the wintry silence.”