Polish Portrait Painters

Jenkins served for a time as a liason to the Polish Army in Exile. He describes Michalski, one of the Polish aides-de-camp of his acquaintance: “Of large size, sceptical about most matters, he belonged to the world of industrial design — statuettes for radiator caps and such decorative items–working latterly in Berlin, which had left some mark on him of its bitter individual humor. In fact Pennistone always said talking to Michalski made him feel he was sitting in the Romanisches Café. His father had been a successful portrait painter, and his grandfather before him, stretching back to a long line of itinerant artists wandering over Poland and Saxony.

‘Painting pictures that are now being destroyed as quickly as possible,’ Michalski said.” [MP 31/27]

At times Powell’s artistic references pertain to a specific work, perhaps previously unknown to many of his readers (for example, The Omnipresent); other times, he is referring to an artistic fantasy, rather than to a real painting (for example, The Boyhood of Widmerpool). Pennistone is modeled on Powell’s friend and commanding officer Alexander Dru; many of the military attachés who appear in MP are modeled closely on officers Powell knew (TKBR 282-283). Was there a real family of artists like the Michalskis or is Powell simply paying homage here to a long tradition of Polish portraiture?

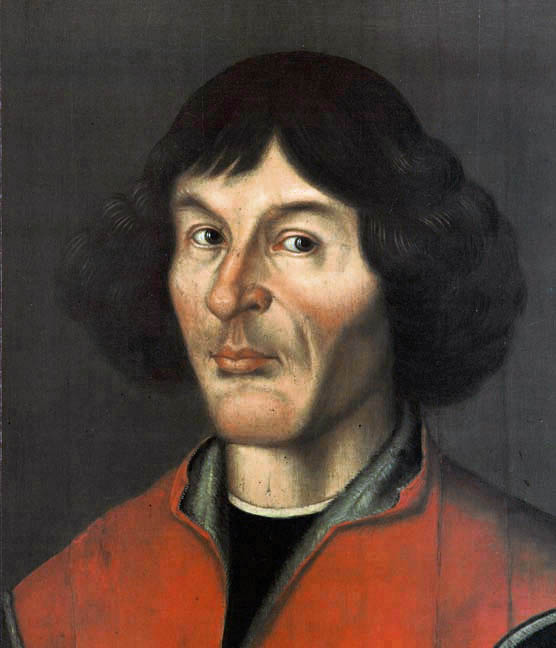

Nicholas Copernicus

artist unknown, 1580

tempera and oil on wood, 20 x 16 in

Regional Museum, Torun, Poland

photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons, source http://www.frombork.art.pl/Ang10.htm

Treasures from Poland, an exhibition of Polish art organized by the Art Institute of Chicago, showed Polish portrait painting dating from the Renaissance (as shown above) to the present. We have found a multigenerational family of Polish painters to illustrate this theme.

Juliusz Fortunat Kossak (1824 – 1899) specialized in historical and battle scenes; his portraits were of the military.

Prince Józef Poniatowski

Juliusz Kossak, 1897

oil on canvas

photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons

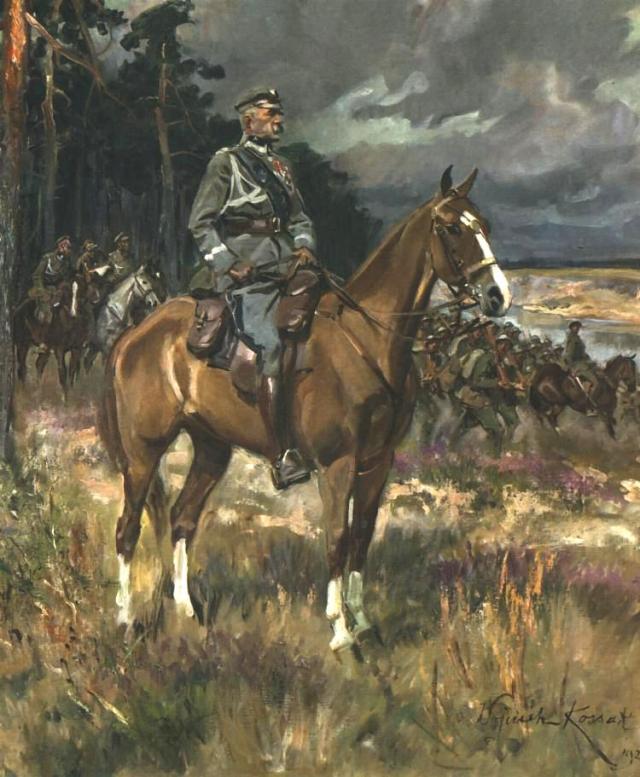

His son, Wojciech Kossak (1856 – 1942), also painted patriotic scenes; his twin brother was a renown freedom fighter. Wojciech’s portrait of Pilsudski is shown below.

Piłsudski on Horseback

Wojciech Kossak, 1928

oil on canvas, 43 x 36 in

National Museum, Warsaw

photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons, source http://artyzm.com/e_obraz.php?id=1616

Lancer Watering Horses

Jerzy Kossak, 1937

oil on cardboard

auctioned by Agra-Art, Warsaw, 2011

All rights to photo reserved by http://www.artvalue.com

Jerzy Kossak (1886-1955) , son of Wojciech, followed the family tradition of painting military scenes but was not as revered as his forebears. He served in the Polish army during the First World War, but we are unsure what he did during the Second.

We have no strong evidence that Powell was thinking about the Kossaks, but we do know that Michalski’s worries about the continued existence of his family’s work reflected what was actually happening in Poland during the war. The Germans occupying Poland were destroying or plundering not only ‘degenerate art‘ and Jewish art, but also any art that might remind the Poles of their national heritage. Some of Wojciech Kossak’s works were among the art that disappeared during the Nazi occupation.

A Corot landscape

Nick and Flynn are flown to Normandy in the company of military attaches from allied nations across the globe. They drive through scenes of recent battles, evidenced by wrecked armored vehicles strewn across the landscape. “This residue was almost always concentrated within a comparatively small area, in fact wherever, a month or two before, an engagement had been fought out. Then would come stretches of quite different country, fields, woodland, streams, to all intents untouched by war.

“In one of these secluded pastoral tracts, a Corot landscape of tall poplars and water meadows executed in light grays, greens and blues, an overturned staff car, wheels in the air, lay sunk in long grass.” [MP 162/157]

Le Batelier de Mortefontaine

Jean Baptiste Camille Corot, 1865-1870

oil on canvas, 24 x 35 in

The Frick Collection, New York

photo in public domain from Wikimedia.org

The landscape to which Nick compares this melancholy vision is one of those by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (French, 1796-1875), a painter of neoclassical training whose landscapes anticipate those of some Impressionists who relied on the capacity of soft-edged shapes to suggest the subtle and fleeting movements in nature observed plein-air. Early in his career Corot worked directly from nature to produce views of Rome and the Italian countryside that startle the viewer with their crystalline clarity of vision. But later in life Corot painted increasingly from memory, producing what he called “souvenirs” of scenes he had studied directly and now recalled as in a dream. It is one of these paintings that we believe Nick has in mind as he himself recalls the dream-like beauty of the Normandy countryside, punctuated by nightmarish souvenirs of recent battles.

Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa

Nick enjoys lunching with the Free French at their headquarters in London. “Their headquarter mess in Pimlico was decorated with an enormous fresco, the subject of which I always forgot to enquire. Perhaps it was a Free French version of Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa, brought up to date and depicting themselves as survivors from the wreck of German invasion.” [MP 145/140]

Théodore Géricault (1791-1825) was a French painter whose heroic depictions of military and equine subjects form a bridge between the neoclassical and romantic styles. Illness ended his life prematurely, and while his works suggest the beginnings of a brilliant career, his enduring fame is almost entirely attributable to his 1819 masterpiece, The Raft of the Medusa.

The Raft of Medusa

Jean Louis Théodore Géricault, 1818-9

oil on canvas, 193 x 282 in

Louvre Museum

photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons

The nominal subject of Géricault’s masterpiece is the 1816 shipwreck of the naval frigate Meduse off the coast of Africa. Its visual content, however, is the agony of passengers and crew members stranded on a flimsy raft of timbers lashed together, surrounded by treacherous waves and voracious sharks. In fact, only 15 of the 147 who actually fled the sinking Meduse on just such a raft survived to tell its story, which included starvation and a resort to cannibalism. The actual event was an international scandal due to the incompetence and self-serving actions of the ship’s captain, allegedly acting under the instructions of his employers. Géricault’s huge, riveting painting secured its creator’s reputation and a permanent place of prominence in the Louvre shortly after the painter’s death.

4 Carlton Gardens, in St. James, was the actual headquarters of the Free French for four years during the War. It is now a private residence, and we have been unable to look inside to see if any fresco was part of the décor. In any case, if Nick’s surmise is correct, that the the fresco in the Free French mess is indeed based on The Raft of the Medusa, its implication is that the collaborators in the Vichy government have abandoned the French people to the Germans in order to save themselves.

Sporting Prints

Jenkins, speaking of their Polish counterparts, asks Pennistone,

You put them through their literary paces as a matter of routine? …

Pennistone laughed at the thought. Though absolutely dedicated to his duties with the Poles, he also liked getting as much amusement out the job as possible.

‘In the course of discussing English sporting prints with Bobrowski,’ he said, ‘a subject he’s rather keen on. It turns out the Empire style in Poland is known as “Duchy of Warsaw”. That’s nice, isn’t it?’ [MP 37/33]

Coursing the Hare

Francis Barlow, Illustration to Richard Blome’s ‘The Gentleman’s Recreation’ 1686

engraved by Hollar, photo in public domain from Wikipedia Commons

source artprints.leeds.gov.uk

We have already shown some sporting prints while discussing the decor of Stringham’s rooms. The heyday of the British sporting prints, mid seventeenth to mid nineteenth century was during the glory days of the British Empire (Snelgrove British Sporting and Animal Prints, 1658-1874 ). The prints were widely circulated and hung in both aristocratic and middle class homes all over England. Francis Barlow (1626-1704 ) is often credited with being a founder of the style, adopting the etching techniques of the Dutch masters to popularize English country scenes. The British love of sport and of sporting prints survives the shrinkage of the Empire, but the production of sporting prints waned with popularization of photography.

The Duchy of Warsaw was created by Napoleon in 1807 as a Polish state and destroyed in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna, which divided it between Russia and Prussia. As far as we can tell, the art associated with the Duchy was much more likely to be military than sporting; see for example, Juliusz Kossak’s portrait of Prince Józef Poniatowski, Commander in Chief of the army of the Duchy.

Outside the Army Council Room

Jenkins, on his way to Finn’s office on the second floor, notes the decor:

Outside the Army Council Room, side by side on the passage wall, hung, so far as I knew, the only pictures in the building, a pair of subfusc, massively framed oil-paintings, subject and technique of each I could rarely pass without re-examination. The murkily stiff treatment of these two unwontedly elongated canvases, although not in fact executed by Horace Isbister RA, recalled his brushwork and treatment, a style that already germinated a kind of low grade nostalgia on account of its naive approach and total disregard for any ‘modern’ development in the painter’s art. The merging harmonies — dark brown, dark red, dark blue — depicted incidents in the wartime life of King George V: Where Belgium greeted Britain, showing the bearded monarch welcoming Albert, King of the Belgians, on arrival in this country as an exile from his own: Merville, December 1st, 1914 in which King George was portrayed chatting with President Poincaré, …. MP [42/37]

Where Belgium Greeted Britain, 4 December 1914

Herbert Arnould Olivier, 1915

oil on canvas, 68 x 143 in

UK, London, Government Hospitality, Lancaster House

© Estate of Herbert Arnould Olivier

Merville, 1 December 1914

Herbert Arnould Olivier, 1916

oil on canvas, 69 x 143 in

UK, London, Government Hospitality, Lancaster House

© Estate of Herbert Arnould Olivier

The subtitle of Where Belgium Greeted Britain is The meeting of King George V and Albert I, King of the Belgians, at Adinkerke, then the last remnant of Belgian territory, on 4 December 1914.The subtitle of Merville is The meeting of King George V and President Poincaré of France at the British Headquarters at Merville, France, on 1 December 1914. These were both painted by Herbert Arnould Olivier (1861-1952), who was an Official War Artist and presented the canvases to King George V in 1924. They did both hang during World War II in the War Office in Whitehall. The Royal Collection presented them to the Government Art Collection in 1983, and they now hang in Lancaster House.

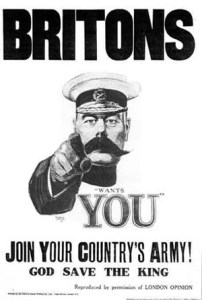

A Bust of Kitchener

Jenkins mentions a bust of Lord Kitchener seen as one climbed the staircase at the War Office. He sees “Kitchener’s cold angry eyes, haunting and haunted, surveying with deepest disapproval all who came that way.” [MP 55/51, 59/54]

Lord Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916) was a hero of the Sudanese war in 1898. At the beginning of World War I, Prime Minister Asquith appointed him Secretary of War. One of his tasks was recruiting, and his poster with the caption “Join Your Country’s Army” became iconic. He was blunt in his assessments of the challenges of the war. A different aspect of his personality was his enthusiasm for collecting the finest Chinese porcelains. (Jenkins mentions this twice times in Dance; see for example, Lord Huntercombe’s remarks about fine china in CCR) [QU 62/61, CCR 165/169]. Lord Kitchener died in 1916 when the cruiser that was taking him to a diplomatic meeting in Russia was sunk by a mine.

Kitchener World War I Recruitment Poster

Alfred Leete 1914

photo in public domain from Wikemedia Commons

Spurling identifies the sculptor of the Kitchener bust as Sir William Reid Dick, RA (1879-1961). [Invitation to the Dance, p. 327]

Dick was commissioned to do a number of pieces for a memorial chapel at St. Paul’s Cathedral dedicated to Kitchener in 1925. A life sized white marble effigy of Kitchener lies on the floor of the chapel. However, as far as we can tell, Dick did not do a bust of Kitchener for the War Office. (see appendix listing Reid Dick’s work in Wardleworth, D William Reid Dick, Sculptor, Farnham, Surrey Ashgate Publishing, 2013).

Lord Kitchener

Richard Belt

bronze bust, reduced

14.5 in high

Listed for auction at The Saleroom.com (accessed 9/20/15)

We wonder whether a better candidate for this image is a bust of Kitchener displayed by Richard Claude Belt (1851-1920) at the Royal Academy in 1917. Bronze copies of this bust have been available at auction inscribed ‘No. 1 Reduction of Bust in War Office.’ (Lot 766 – Richard Claude Belt (1851-1920), a bronze bust of Lord Kitchener together with other memorabilia, The Saleroom.com, accessed 9/20/15). Belt’s bust of Kitchener shows those “cold angry eyes” that guard the staircase.

Memling, Teniers, Brouwer

While overseeing the Belgian attaches in London, Nick muses:

On the whole, a march-past of Belgian troops summoned up the Middle Ages or the Renaissance, emaciated, Memling-like men-at-arms on their way to supervise the Crucifixion or some lesser martyrdom, while beside them tramped the clowns of Teniers or Brouwer, round rubicund countenances, haled away from carousing to be mustered in the ranks. These latter types were even more to be associated with the Netherlands contingent—obviously a hard and fast line was not to be drawn between these Low Country peoples—Colonel Van der Voort himself an almost perfect example. [MP 93/88]

The Martyrdom of St. Ursula

Hans Memling, 1489

oil on panel, 15 x 14 in

Hans Memling Museum, Bruges, Belgium

photo in public domain from the Yorck Project via Wikimedia Commons

Hans Memling (1430-1494) was a German-born Flemish painter, the disciple of Rogier van der Weyden and a master of Rogier’s jewel-like early Renaissance realism. Memling was much adored in both the Low Countries and Italy for his many portrait paintings and his religious scenes, though not battle scenes in which one might expect to find the types to which Nick alludes. But sure enough, men-at-arms populate the odd Memling martyrdom, such as this one of St. Ursula in the Memling Museum in Bruges.

Guardroom Scene with the Deliverance of St. Peter

David Teniers the Younger, 1645-7

oil on copper, 14 x 20 in

The Wallace Collection, London

photo in public domain from BBC Your Paintings via Wikimedia Commons

Whether or not the reader will find the Memling men-at-arms to be “emaciated,” they will certainly seem so in comparison to “the clowns of Teniers or Brouwer.” The Teniers whom Nick mentions is undoubtedly David Teniers the Younger (1610-1690), one of four generations of Flemish painters and the most universally admired. His work included, though was not limited to, scenes of village life populated by the gentry and the carousing peasantry.

Inn with Drunken Peasants

Adriaen Brouwer, 1625-1626

oil on panel, 8 x 10 in

Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague

photo in public domain from G. Knuttel Wzn, Openbaar Kunstbezit, vol. IV, no. 9 via Wikimedia Commons

An influence on Teniers’ imagination is believed to be Adriaen Brouwer (1605-1638), a Flemish painter who not only took the carousing of the peasantry as a subject but also as a lifestyle, and is thought to have died of its excesses. Brouwer’s types are rather less affectionately portrayed than Teniers’, but in the works of both painters, their “round rubicund countenances” are easy to spot. Apparently, the Belgian troops under Nick’s gaze are no more refined of countenance than their Renaissance forebears.

Gainsborough Hats

At the theater, Nick sees Prince Theodoric sitting with Lord Huntercombe, both wearing dark suits, and Lady Huntercombe, “in a rather different role implied by her pre-war Gainsborough hats” who “was formidable in Red Cross commandant’s uniform.” [MP 103/98]

Voluntary Aid Detachment Uniform

British Red Cross (Beatrice Jane Hayward, center), 1945

from http://www.qarnac.co.uk

Nick has previously compared Lady Huntercombe to Gainsborough’s portrait of Mrs. Siddons. The Gainsborough hat became famous based on another portrait painted about the same time (1785). He exhibited his portrait of Georgiana, Duchesss of Devonshire, at the Royal Academy. She was a fashion setter who designed the hat herself. After the exhibition, large black hats with generous brims and prominent feathers were the vogue in London. The style, sometimes called the ‘Gainsborough chapeau’ or the ‘portrait hat’, has been in and out of fashion ever since.

Georgiana, Duchess of Devpnshire

Thomas Gainsborough, 1783

oil on canvas, 50 x 40 in

Chatsworth House, Derbyshire

photo in public domain from wikiarts.org via Wikimedia Commons

Two interesting stories — Georgiana’s notorious adventures and the adventurous travels of her portrait after her death — are beyond the millinery goals of this post. The portrait was returned to Chatsworth House when the 11th Duke of Devonshire bought it back at auction in 1994 and now is displayed there next to another portrait of Georgiana by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Royal Portrait of King Leopold

Jenkins, sent to the Cabinet Offices to pick up some Belgian papers, reflects:

The position of the King of the Belgians was delicate. Formally accepted as monarch of their country by the Belgian Government in exile, the royal portrait hanging in Kucherman’s office, King Leopold, rightly or wrongly, was not, officially speaking, very well looked on by ourselves. His circumstances had been made no easier by a second marriage disapproved by many of his subjects. [MP 109/104 ]

Leopold III (1901-1983) was king of Belgium from 1934-1951. When Germany invaded Belgium in 1940, Leopold personally surrendered unconditionally on May 28, and chose to remain in Belgium rather than accompany the Belgium government into exile. Churchill publicly criticized his decision to surrender. Leopold said he felt compelled to stay in country with his subjects, but many Belgians, especially in the government-in-exile, saw him as a collaborator with, rather than as a prisoner of, the Germans

His first wife died in a car accident in 1935 In 1941 he married Mrs. Lilian Baels. The religious wedding ceremony did not comport with Belgian law, and their child was born 7 months later.

Both his actions during the war and his second marriage were unpopular with many Belgians, and he renounced the throne under pressure in 1951.

The Cenotaph

Jenkins and Farebrother walk together into Whitehall.

Farebrother suddenly raised his arm in a stiff salute. I did the same, taking my time from him, though not immediately conscious of whom we were both saluting. Then I quickly apprehended that Farebrother was paying tribute to the Cenotaph, which we were at the moment passing. [MP 121/116]

The Cenotaph

Sir Edwin Lutyens, 1919

Height 35 feet

Whitehall, London

photo by Creative Commons license from Wikimedia Commons, taken April 14, 2014, uploaded by Godot13

The Cenotaph (Greek for empty tomb) in Whitehall was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and executed in Portland Stone by Holland, Hannens & Cubitts, 1919-1920, as a memorial to the dead of the Great War. Lutyens (1869-1944) works ranged from British country houses to monuments of British India, including many of the government buildings in New Delhi. His Cenotaph was much copied, and he designed at least 50 memorials to World War I, including the India Gate, which was designed as the All India War Memorial.

Powell briefly alluded to World War I memorials in BM (see The Haig Statue), but now as World War II is approaching its end, he is repeatedly reminding us of the First World War, also memorialized by Olivier’s paintings and the bust of Kitchener. The Cenotaph is now seen as a memorial to British military lost in both World Wars and in subsequent conflicts.

Jenkins Reads Proust

Reading Remembrance of Things Past one night in bed, Jenkins is struck by a passage that he quotes extensively. The writing is typically Proustian: a memoir of a conversation that The Narrator had with the Turkish Ambassadress at a party given by a Princesse, replete with myriad characters, seemingly endless subordinate clauses, gossipy asides about a Prince Odoacer, and parenthetical digressions. [MP 124-125/119-121 ]

Powell has often been called the British Proust because both Dance and Remembrance are long novels, reminiscences of time and milieu, in which haut bourgeois narrators recall their lives among the aristocratic and cultured. Powell, the perceptive critic, dismissed the analogy in The Paris Review (1978) :

INTERVIEWER [Michael Barber]

Could we just settle the comparison to Proust? I believe you reject it?

POWELL

Well, I do to this extent: that I’m a great admirer of Proust and know his works very well. But the essential difference is that Proust is an enormously subjective writer who has a peculiar genius for describing how he or his narrator feels. Well, I really tell people a minimum of what my narrator feels—just enough to keep the narrative going—because I have no talent for that particular sort of self-revelation.

The painting references in the passage quoted by Jenkins are to a “hunting scene by Wouwerman” and to La Gioconda, the nickname given to a youth by “his fellow inverts. ”

We first realized that the Proust text is a pastiche, or as Spurling says, a passage that “seems to be known only to Nicholas Jenkins” (Invitation to the Dance, p. 542), when we found that Proust mentions neither La Gioconda (The Mona Lisa) nor Philips Wouwerman (1619-1668), a master of the Dutch Golden Age, especially noted for his portrayal of horses in military and hunting scenes. Proust does pay homage to other Golden Age painters, like Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Wouwerman’s teacher Hals.

Setting Out on the Hunt

Philips Wouwerman, 1660-1665

oil on oak panel, 18 x 25 in.

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons,

source Web Gallery of Art

Powell draws attention to the homosexual motif in Remembrance by having Proust’s Narrator hear La Gioconda as the nickname for a young man. Da Vinci painted Mona Lisa ostensibly as a portrait of Lisa Gherardini, the wife of Francesco del Giocondo, but one of many theories about the actual model names him as Gian Giacomo Caprotti, Leonardo’s long-time apprentice. Da Vinci’s painting of Saint John the Baptist, shown below, was modeled on Caprotti and has some resemblance to Mona Lisa. Scholars in Proust’s time wrote of Leonardo’s suspected homosexuality and possible relationship with Caprotti (CJ Farago ed Biography and Early Art Criticism of Leonardo Da Vinci U. Of Chicago 1999).

Saint John the Baptist

Leonardo da Vinci, 1513-1516

oil on panel, 27 x 22 in.

The Louvre

photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commns

We are among those guilty of speculating about the actual person who serves as an artist’s or novelist’s model. After “quoting” Proust, Powell teases those who search for real counterparts of fictional characters; Jenkins says:

This description of Prince Odoacer was of special interest because he was a relation — possibly a great-uncle — of Theodoric’s. I thought about the party for a time, whether there had really been a Turkish Ambassadress, whom Proust found a great bore; then, like the Narrator himself in his childhood days, fell asleep early. [MP 125/121 ].

Of course, there is no Prince Odoacer in Remembrance. The historical Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths from 475 to 526, assinated Odoacer, king of Italy, in 493.

Jan Steen

Jenkins writes about the Dutch military attaché Colonel Van der Voort, “whose round florid clean-shaven face looked more that ever as if it peered out of a Jan Steen canvas. Van der Voort was in his most boisterous form, seeming to belong to some anachronistic genre picture, Boors at an Airport or The Airfield Kermesse, executed by one of the lesser Netherlands masters. [MP 159/154]

Rhetoriticians at a Window

Jan Steen, 1661-1666

Oil on canvas, 30 x 23 in

Philadelphia Museum of Art

photo in public domain from Wikimedia.org

Jan Steen (1626-1679) qualifies as a lesser Dutch master from the Golden Age. He went to the same Latin school attended by his contemporary, Rembrandt van Rijn. He was so well known for his boisterous genre paintings that a “Jan Steen household” became a Dutch phrase for a chaotic scene, “the standard by which all later family dysfunction can be measured” (Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History). The men pictured at the left are members of a rhetoric club, a type of dramatic and literary society popular at the time.

Jenkins has previously compared Colonel Van der Voort’s face to those of clowns by Teniers or Brouwer. The round face of the man at the lower left, reading a paper to his companions, reinforces the image.

A Kermesse, by the way, is a Dutch or Flemish term for a fair or festival, originating from kerk (church) and mis (mass), and now used in English as “kermis” or “kirmess.”

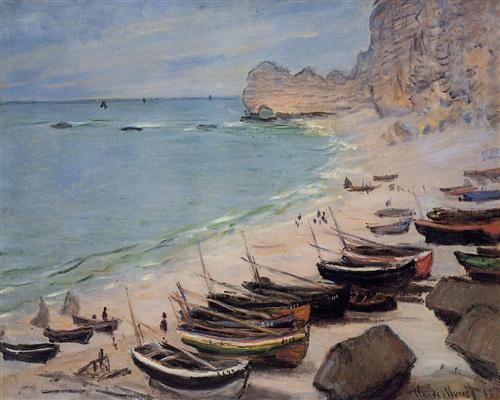

Impressionist Views of Normandy

At the Grand Hotel in Cobourg, Normandy, Nicholas sees:

In the early morning light, the paint on the side walls of the hotel had taken on a pinkish tone, very subtle and delicate, blending gently with that marine vapourness of atmosphere so enthusiastically endorsed by the Impressionists when they painted this luminous northern shore. [MP 170-171/167-168 ]

Boats on the Beach at Etretat

Claude Monet, 1883

oil on canvas

private collectdion

photo in public domain from WikiArt.org

Impressionsts, Normandy — Monet immediately springs to mind, but we think that Whistler’s seascapes are more appropriate to this reference.

Harmony in Blue and Silver

James McNeill Whistler,

oil on canvas, 20 x 30 in

Isabella Steward Garner Museum, Boston

http://www.gardnermuseu.org

Proust stayed at the Grand Hotel in Cobourg every summer from 1907 through 1914. Jenkins recalls the connection:

‘Just spell out the name of that place we stopped over last night, Major Jenkins,’ said Cobb.

‘C-A-B-O-U-R-G, sir.’

As I uttered the last letter, scales fell from my eyes. Everything was transformed. It all came back — like the tea-soaked madeleine itself — in a torrent of memory … Cabourg … We had just driven out of Cabourg … out of Proust’s Balbec. [MP 172/167-168]

Jenkins lists many of Proust’s characters who had visited the Grand Hotel: Albertine, Saint-Loup, Bloch, Charlus. “Here Elstir had painted; Prince Odoacer played golf.” [MP 172/167-168]

We quote Proust without pastiche:

But just as Elstir, when the bay of Balbec, losing its mystery, had become for me simply a portion interchangeable with any other, of the total quantity of salt water distributed over the earth’s surface, had suddenly restored to its personality of its own by telling me that is was the gulf of opal painted by Whistler in his Harmonies in Blue and Silver … [In Search of Lost Time, Volume III: The Guermantes Way Enright/Kilmartin/Moncrieff translation]

Whistler was an important figure to Proust; among painters, in his novel, Proust mentions only Vermeer and Rembrandt more than Whistler . They met only once, and Proust came away with a pair of Whistler’s gloves as a souvenir. Whistler actually painted Harmonies in Blue and Silver at Trouville-sur-Mer, a number of miles east of Cabourg, but on the shifting sands of fact and fiction that Proust and Powell sift so elegantly, we can easily join Jenkins in imagining the beach at Balbec.

Ensor’s Entry of Christ into Brussels

Nick’s cohort of officers makes its way across Belgium into Brussels. “When we drove into the city’s main boulevards, their sedate nineteenth-century self-satisfaction, British troops everywhere, made our cortege somewhat resemble Ensor’s Entry of Christ into Brussels, with soldiers, bands and workers’ delegation.” [MP 174/169-170]

Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889

James Ensor, 1888

oil on canvas,100 x 170 in.

Getty Center, Los Angeles

© 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SABAM, Brussels

Nick is referring to James Ensor’s huge and arresting painting, also known as Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889, now in the Getty Museum. Because of copyright limitations, we show only a thumbnail image; go to the Getty, or at least to the Getty website, to appreciate the energy of this painting or just to search the canvas for “Colman’s ‘Mustart’ advertisement spelt wrong.” [MP 174/169-170]

Ensor was, before Rene Magritte, perhaps Belgium’s most well-known modernist painter. He was a controversial figure in art due to his radical expressionist tendencies before the term Expressionist came to describe a recognized movement in the twentieth century. Christ’s Entry into Brussels was stiff medicine even among the coterie that Ensor formed around him, known as Les XX, and, hence, was not exhibited publicly until 1929, thirty years after its creation. The painting depicts a Christ almost invisible amidst a throng of workers, clerics, politicians, vagrants, revelers and grotesques, deliberately rendered by Ensor in a rude hand that simultaneously points back toward Pieter Brughel and forward to the likes of George Grosz and Otto Dix.

Nick’s evocation of Ensor’s vision does not, we think, place the emphasis on the Allied officers’ role as saviors of Belgium, but rather suggests the near invisibility of their arrival amidst the churning chaos during the wind-down of the war.

Art Nouveau Wallpaper

Jenkins attends an Indian embassy party. “The huge saloons, built at the turn of the century, were done up in sage green, the style of decoration displaying a nostalgic leaning toward Art Nouveau, a period always sympathetic to Asian taste.” [MP 204-205/199]

The term Art Nouveau was introduced in the 1890s in a Belgian journal, L’Art Moderne. The style prospered in France, propelled in part by a gallery, L’Art Nouveau, owned by Siegfried Bing. The movement championed flowing designs based on shapes derived from plants and vines. Think of the iron-work entries of the Paris Metro and the graphics used to advertise that subway system. The French vogue for japonisme is seen in many of the works. William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement influenced British Art Nouveau.

We can imagine the wallpaper shown at left in the embassy rooms. C.F.A. Voysey (1857-1941) was an English architect and designer who was particularly well known for his wallpaper. The Victoria and Albert Museum has a fine collection of his work. In 1896 The Studio, a magazine that championed Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts, proclaimed, “Now a ‘Voysey wall-paper’ sounds almost as familiar as a ‘Morris chintz’ or a ‘Liberty silk’.” ( Studio International, vol. 7, p. 209 ) Exactly which works qualify as Art Nouveau is debated; some critics dismiss Voysey’s work as too “Art Nouveau artsy” and others separate his pieces from the Art Nouveau movement.

Monuments in St. Paul’s

On a Sunday in August, 1945, Jenkins accompanied the Allied military attachés to a service of General Thanksgiving at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Seated in the south transcept, he surveyed the surrounding “huge marble monuments in pseudo-classical style.” [MP 219/214 ] Recalling that some of the monuments had been described in The Ingoldsby Legends, a book that his mother read to him in childhood, he remembered: [MP 221/216 ]

… Sir Ralph Abercrombie going to tumble

With a thump that alone were enough to dispatch him

If the Scotchman in front shouldn’t happen to catch him.

The Ingoldsby Legends are stories and poems published between 1837 and 1847 by Richard Harris Barnham. Jenkins is quoting from the one of the poems, The Cynotaph, which begins:

Oh! where shall I bury my poor dog Tray,

Now his fleeting breath has pass’d away?

A ‘cynotaph’ or ‘dog’s tomb’ is not to be confused with a ‘cenotaph.’ In the poem Barnham proceeds to exclude St. Paul’s as a burial place after reviewing memorials such as those of Abercrombie and Sir John Moore.

Memorial for Lieutenant General Sir Ralph Abercrombie, K. B.

Sir Richard Westmacott, RA, 1801

Marble

St. Paul’s Cathedral, London

photo courtesy of Geogre P. Landow and the Victorian Web

Sir Ralph Abercrombie or Abercromby (1734-1801) was in the British Army from 1756 until his death. He served in the Seven Years War, in the French Revolutionary Wars, including important commands in the Caribbean, and in Ireland during the Irish rebellion. He was a Lieutenant-General when he died while leading troops in battles to regain Egypt from France. After his death, the House of Commons voted that a monument be built in his honor in St. Paul’s. Sir Richard Westmacott (1775-1856) did this momument early in his productive career, during which he produced the Achilles statue honoring the Duke of Wellington and many others still visible in the squares of London and elsewhere in the Commonwealth.

Coincidentally, the French writer Stendhal also knew these monuments. Powell admired the diaries of Stendhal more than he enjoyed the pioneering realistic novels The Red and The Black (1830) and The Charterhouse of Parma (1839) [TKBR p.181]. When Stendhal visited St. Paul’s in August, 1817, he ridiculed the heavy style of the Abercrombie monument; Jenkins seems to accept this criticism but reflects:

Nevertheless, one felt glad it remained there. It put on record what was then officially felt about death in battle, begging all that large question of why the depiction of action in the graphic arts had fallen in our own day almost entirely into the hands of the Surrealists. [MP 221/216 ]

Monument to Lieutenant-General Sir John Moore, K.B.

John Bacon, Jr,

St. Paul’s Cathedral, London

photo courtesy of George P. Landow and the Victorian Web

Stendahl preferred the tomb of Sir John Moore (1761-1809), another Lieutenant-General honored with a memorial in St. Paul’s. His service included the American War of Independence, the French Revolutionary Wars, the Irish Rebellion, the Anglo-Russian invasion of Holland, and the war against France in Egypt and Syria, ending with his death at the battle of Corunna during the Penisular War in Iberia. John Bacon, Jr. (1877-1859) sculpted Moore’s monument, five other monuments in St. Pauls, and many others in Westminster Abbey and other British sites. Jenkins gives Barnham’s desciption of the scene:

Where the Man and the Angel have got Sir John Moore,

And are quietly letting him down through the floor,

Monument to Major General Ponsonby

designed by R. Theed, RA; executed by E. H. Bailey, RA, 1815

marble

St. Paul’s Cathedral, London

photo by Stephencdickson via Wikimedia Commons

Jenkins looked around for what Barnham called “that Queer-looking horse that is rolling on Ponsonby,” but did not see it because Ponsonby’s monument is at the north end of the cathedral. [MP 222/217].

The service seemed cold and depressing to Jenkins; however, the monuments recalled warmer days of his childhood before World War I. The music of time seems to echo off the monuments, which patriotically commemorate the protracted hostilities with the French in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Barnham’s poem,The Cynotaph, reveals a Victorian sense of humor regarding the bombastic character of the sculptures in St. Paul’s. But the arch-Modernist Jenkins, exhausted by the unremitting sorrows of the war, is touched by a faint nostalgia for a pre-Modern moment when artists could celebrate patriotic valor without a hint of self-consciousness or embarrassment.