Spy’s Caricature of Lord Vowchurch

Jenkins knows of Lord Vowchurch, Mrs. Conyers father, both from circulating stories about him, “one of those men oddly prevalent in Victorian times who sought personal power through buffoonery,” and from a caricature by Spy, which had appeared in Vanity Fair and now hung in the billiard-room at the Conyers’ home, Thrubworth [ALM 8/4].

Sir Leslie Ward (1851-1922) drew 1325 cartoons for Vanity Fair between 1873 and 1911, signing them as “Draw” or “Spy.” Ward began exhibiting his work in 1867 while at Eton. Lithographs of many of his portraits sold widely. Vanity Fair has been the title of at least 5 different magazines, but, of course, Jenkins need not specify that he is referring to the British Vanity Fair, which was published weekly from 1868 to 1914. A full page lithographic contemporary portrait was a central feature of most editions, and Ward did so many of these that they became know as ‘Spy cartoons.’

We display Spy’s caricature of George Biddel Airy because Airy, like Lord Vowchurch, has a grey frock-coat, top hat, and side whiskers. In the caricature, Jenkins sees “the bad temper for which he was as notorious at home as for his sparkle in Society, neatly suggested under the side whiskers by the lines of his mouth.”

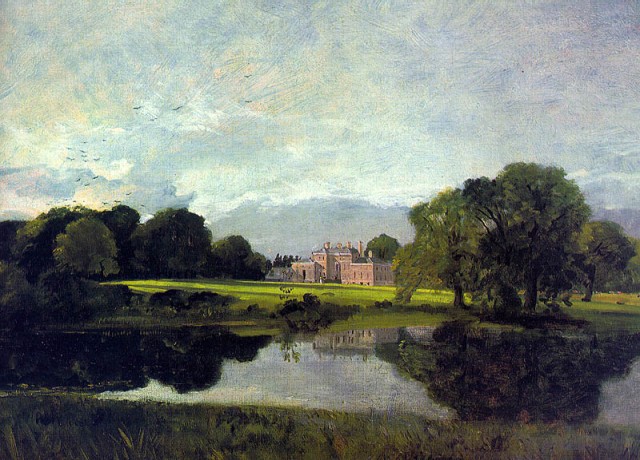

Constable, Pepys, and Veronese at Dogdene

In his introduction to the Sleaford family at the beginning of At Lady Molly’s, Nick evokes his image of Dogdene, the Sleaford great house: “I also knew Constable’s picture in the National Gallery, which shows the mansion itself lying away in the middle distance, a faery place set among giant trees beyond the misty water-meadows of the foreground in which the impastoed cattle browse . . . .” [ALM 13/10]

John Constable (1776-1837) was a British painter known for sweeping landscapes of his native Suffolk County, the Salsbury Plain and its famous cathedral, and views of the then-rural outskirts of London. Constable was known for his impasto, paint applied thickly so that brush strokes were visible, which was not a fashionable technique in his day. He paired painstaking attention to directly-observed detail with compositions that revealed his belief in a Nature endowed with sentiment. Hence, he is identified as a Romantic painter, akin to his contemporary J. M. W. Turner. While Constable’s work met with consistent critical esteem within his own lifetime, he struggled for commercial success and had to resort to commissioned portraits of affluent sitters in order to support his family.

Portraits of great houses were not common in Constable’s output, and the Constable Dogdene in the National Gallery is an invention of Powell’s, as is Dogdene itself. Constable favored landscapes into which picturesque cottages or humble farmsteads were nestled, rather than those surrounding pretentious mansions. Nevertheless, at least two or three paintings by Constable of Malvern Hall in Warwickshire exist, and suggest the sort of scene Nick has in mind when he remembers Dogdene. The one shown here dates from 1809 and is now in the collection of the Tate Museum.

Malvern Hall

John Constable, 1809

oil on canvas, 21 X 33 in

Tate Museum

image in public domain from Wikimedia Commons

Nick goes on to quote a (fictional) entry in the diary of the redoubtable Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), who recounts a visit to Dogdene and a typical sexual adventure there with a housekeeper in the Sleaford employ. On her way to more secluded parts of the house, “The Housekeeper was mighty civil, and showed us the Great Hall and stately Galleries, and the picture by P. Veronese that my Lord’s grandfather did bring with him out of Italy, a most rare and noble thing.” (ALM 11)

Paolo Veronese’s (1528-1588) greatest commissions were for clients throughout the Veneto, but he is most readily identified with his huge Venetian paintings of Biblical and classical mythological and historical scenes (see Alexander receiving the Children of Darius after the Battle of Issus in QU).

The Allegory of Love — Infidelity

Paolo Veronese, ~ 1570

76 X 76 inches

The National Gallery, London

image in public domain from WikiMedia Commons

Veronese took inspiration from the high Renaissance schools of both Titian and Raphael and emerged with a synthesis that is now usually dubbed Mannerism, alluding to a kind of exaggeration of qualities that take his paintings somewhere beyond the simpler naturalism that his forbears aspired to. Later in Dance [HSH 209/225] the Dogdene Veronese is identified as Iphigenia. There is not a known Veronese Iphigenia, so we show this allegory called Infidelity, which seems appropriate to the tone of ALM.

The Barbizon School

Chips Lovell’s father was a painter whose “insipid, Barbizonish little landscapes, not wholly devoid of merit, never sold beyond his own circle of friends. ” [ALM 16/14 ]

Fontainebleau, Oak Trees at Bas-Breau

Camille Corot, 1832-3

Oil on paper laid down on wood; 15 5/8 x 19 1/2 in.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The ‘Barbizon school‘ refers to a group of French nineteenth century landscape painters, including Jean-Francois Millet, Theodore Rousseau, and Camille Corot, who painted realistically from nature, working outdoors in the Forest of Fontainbleau, and often meeting in the nearby village of Barbizon. Their work departed from the neoclassical landscapes of Poussin and Claude Lorraine. Among their inspirations was Constable’s exhibit at the Paris Salon of 1824.

Wilson and Greuze at the Jeavon’s

Chips Lovell brings Nick to the Jeavons home, where Nick surveys the scene upon entering the drawing room: “Some of the furniture was obviously rather valuable: the rest, gimcrack to a degree. Pictures showed a similar variation of standard, a Richard Wilson and a Greuze (these I noted later) angling among pastels of Moroccan native types.” [ALM 24/21]

Richard Wilson (1714-1782) was a Welsh-born painter, one of the earliest British landscape painters and well-known for his idealized bucolic scenes in the tradition of Claude Lorrain. Wilson became a founding member of the Royal Academy. Pictured here is his view of the Thames at Twickenham from 1762.

Richard Wilson, c. 1762

oil on canvas, 18 X 29 in

The Tate

image in public domain from Wikimedia Commons

We have interspersed a Moroccan pastel of a courtyard in Marrakech, painted contemporary to the setting of ALM, to highlight the eclectic nature of the Jeavon’s collection.

L’accordée de village

Jean-Baptise Greuze, 1761

oil on canvas, 36 X 42 in

Musee de Louvre

image in public domain from Wikimedia Commons

Jean Baptiste Greuze (1725-1805) was a French painter who aspired to be known for his historical compositions but whose fame was primarily based on masterful “genre scenes,” riveting melodramas of bourgeois domestic life that embody moral lessons. In spite of his vexed relationship with the French Royal Academy regarding the status of such subject matter in the traditional hierarchy of painting subjects, Greuze was immensely popular with a bourgeois audience during his own lifetime. By the time of his death, however, Greuze’s reputation had fallen precipitously, due to the sentimental nature of his domestic scenes, but in most recent times a renewed esteem for his draughtsmanship and formal mastery have kept his name in currency. We aren’t told which Greuze hung in the Jeavons’s drawing room, but here is his “Village Wedding,” of 1761, now in the Louvre.

Dutch Genre Painting

The thought of General Conyers playing his cello reminds Jenkins of “Dutch genre pictures, sentimental yet at the same time impressive, not only on account of their adroit recession and delicate colour tones, but also from the deep social conviction of the painter.” [ALM 72/69]

Rural Musicians

Adriaen van Ostade, ~1655

oil on panel, 15 X 12 in

Hermitage Museum

images in public domain from Wikimedia Commons

When Dutch painting flourished in the seventeenth century, painters commonly devoted themselves to scenes of everyday life, called genre paintings. Maybe Nick was thinking of something like this cellist in a painting by Adriaen van Ostade (1610-1685).

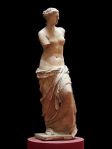

A Statue of Venus

Jenkins saw Mona as “like a strapping statue of Venus, conceived at a period when a touch of vulgarity had found its way into classical sculpture. “ [ALM 107/105 ]

Venus de Milo

Alexandros of Antioch

Between 130 and 100 BC

Marble

Louvre Museum

image public domain from Wikimedia Commons

We have already seen how Quiggins thought contemporary sculptors might treat statuesque Mona. Now Jenkins is clearly not referring to the classic Venus de Milo but looking toward later visions of the goddess of love.

A Portrait by Lawrence

At Thrubworth, Jenkins sees a “full-length portrait by Lawrence, of an officer wearing the slung jacket of a hussar.” Errigde explains that this is the “4th Lord Erridge and 1st Earl of Warminster,” a contemporary of the Duke of Wellington. [ALM 149/149]

Charles Vane-Stewart, The Third Marquess of Londonderry

Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1812

The National Portrait Gallery

oil on canvas, 57 X 46 in. photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830) was a portrait painter and president of the Royal Academy. His flattering portraits were in demand by the artistocracy. This portrait by Lawrence shows the Third Marquess of Londonderry in a hussar’s uniform. A very similar portrait, dated 1814, is in the National Gallery in London on loan from the executors of the late 9th Marquess of Londonderry. Lawrence charged more for more complex paintings, so the full-length portrayal and the detail of the hussar’s uniform showed the affluence or at least the extravagance of the Erridge’s ancestor.

The School of Paris and The Celtic Twilight

Visits to the Jeavons’ household help Nick begin to fill out his picture of Molly Jeavons: “She might have the acquisitive instinct to capture from her first marriage (if that was indeed their provenance) such spoils as the Wilson and the Greuze, while remaining wholly untouched by the intellectual emancipation, however skin-deep, of her generation: the Russian Ballet: the painters of the Paris School: novels and poetry of the period: not even such a mournful haunt of the third-rate as the Celtic Twilight had played a part in her life.” [ALM 158/]

The Marketplace, Vitebsk

Marc Chagall, 1917

oil on canvas Oil on canvas; 26 x 38 in. (66.4 x 97.2 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum

© 2011 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

The Paris School alludes not so much to a style of art but to Paris’ role as the magnet for forward-thinking artists of every stripe during the first part of the 20th century, up until World War II. In the period before World War I, which would be when Lady Molly was coming of age as the mistress of Dogdene, the Paris School would have included Picasso and Miro among its painters, Brancusi and Modigliani among its sculptors. It is Lady Molly’s immunity to so many new strains of art — Cubism, Surrealism, the magical realism of Chagall, the expressionism of Soutine, the elongated figures of Modigliani — that signals her lack of enthusiasm for art, despite the Wilson and Greuze on her walls. We could show any number of the diverse output of the School of Paris, but we have chosen here an artist not actually mentioned in Dance.

William Butler Yeats

John Butler Yeats, Portrait of his son, W.B. Yeats; frontispiece to W.B. Yeats, Celtic Twilight, 1896

The Celtic Twilight refers to a renaissance of Irish literature focused on a revival of interest in Gaelic folklore and Irish nationalism at the end of the 19th century. The name itself derives from William Butler Yeats’ 1893 collection of tales and poems entitled “The Celtic Twilight.” The Celtic Twilight also inspired a number of visual artists and an increased interest in older designs like the Celtic cross. Jenkins is not alone in disparaging this movement; in Finnegan’s Wake, James Joyce wrote of the “cultic twalette,” but it should be remarked that its luminaries include not only Yeats but Sean O’Casey, John Millington Synge, and George Bernard Shaw.

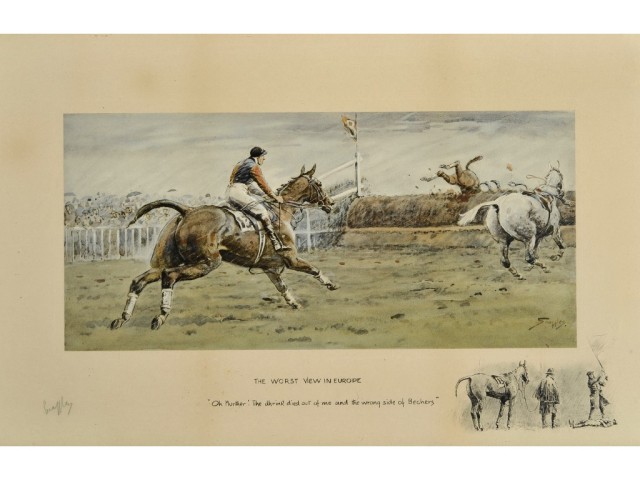

A Sergeant from a Snaffles

Dicky Umfraville talks about the artistic aspirations of his ex-wife, Lady Anne Stepney, but adds that he, himself, “Can’t tell a Sargent from a ‘Snaffles.’” (ATM p 181)

A snaffle is a common type of horse bit. ‘Snaffles’ was Charles Johnson Payne (1884-1967), who worked as a graphic artist during World War I but after the war, concentrated on prints of sports: hunting, polo, fishing, pig-sticking in India, racing. The example shown below, from a Lawrences Auctioneers catalog, shows some of Snaffles characteristics, like a penciled signature and a humorous caption. An impressed mark of a pair of interlocking snaffles, often part of his print borders, is reportedly present, but we cannot see it on this reproduction.

Bus Horses in Jerusalem

John Singer Sargent, 1905

watercolor on paper, 16 X 21 in

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Isabella Stewart Gardner

John Singer Sargent, 1888

oil on canvas, 76 x 32 in.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) was prolific, producing over 900 oils, over 2000 watercolors, and numerous drawings. He was born in Florence to American parents, studied in Paris, and spent much of his life painting in London. His portraits of the rich and famous were in demand on both sides of the Atlantic. This portrait of one of his patrons, Isabella Stewart Gardner, showed so much flesh that her husband asked her not to display it publicly while he was alive. We have highlighted a watercolor of horses to show how his elegant realism contrasted with Snaffles’ jocularity. Umfraville’s mot is the only mention of the Sargent in Dance, so we know nothing of Powell’s opinion of him. Rodin called him “the Van Dyck of our time;” (John Singer Sargent: The Early Portraits, 1998, p 150), but others preferred the Modernism that figures so prominently in Dance rather than Sargent’s realism. Roger Fry called the work “wonderful indeed, but most wonderful that this wonderful performance should ever have been confused with that of an artist.” Ivan Kenneally, writing for an exhibit of Sargent watercolors at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, examines Sargent’s relation to Modernism and puts Fry’s put down to rest.

Portraits of Pepys

Jenkins meets Widermerpool at Lady Molly’s. Widermerpool is looking wan but revives when he starts to talk about an invitation to visit Dogdene. “The reflection seemed to give him strength. I thought of Pepys and the ‘great black maid’; and immediately Widmerpool’s resemblance to the existing portraits of the diarist became apparent. He had the same put-upon, bad-tempered expression. Only a full-bottomed wig was required to complete the picture.” [ALM 194/195]

Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) was an administrator of the Royal Navy and a member of Parliament during the reigns of Charles II and James II. He is famous for the diary that he wrote from 1660 to 1669, first published in 1825, in which he gives a vivid account not only of his personal affairs but of the whole of London during the Restoration. Powell was fascinated by this period of English history and wrote a book on John Aubrey, who like Pepys, is a major source on the intellectual and social history of the period. Aubrey and Pepys were well acquainted; both belonged to the Rota club, a London debating society.

This passage toward the end of ALM refers back to Powell’s pastiche of a Pepys’ diary entry early in ALM (see Constable, Pepys, and Veronese at Dogdene). Pepys wears a long (‘full-bottomed’) wig to match the seventeenth century fashion for men to keep their hair long. Wigs became popular in England when Charles II returned to the throne in 1660, bring the fashion from France, where he had been in exile. Pepys wrote in his diary:

“3rd September 1665: Up, and put on my coloured silk suit, very fine, and my new periwig, bought a good while since, but darst not wear it because the plague was in Westminster when I bought it. And it is a wonder what will be the fashion after the plague is done as to periwigs, for nobody will dare to buy any haire for fear of the infection? That it had been cut off the heads of people dead of the plague.”

Portrait of Samuel Pepys

Engraved by T. Bragg for the 1825 edition of Pepys Diary

original portrait by Geoffrey Kneller

Kenneth Widmerpool lunching at his Club

Mark Boxer

cover illustration for At Lady Molly’s

Flamingo edition, 1984

Pepys is dour enough in his portrait, but our vision of Widermerpool is also informed by this caricature drawn by Mark Boxer, which appears on the cover of the Flamingo edition (1984) of ALM.

Our Van Troost

General Conyers makes some rambling reflections on Dogdene:

“The there is the Veronese (see our post Constable, Pepys, and Veronese at Dogdene). Geoffrey Sleaford has been advised to have it cleaned, but won’t hear of it. Young fellow called Smethyck told him. Smethyck saw our Van Troost and said it was certainly genuine.” [ALM 226/227]

Portrait of a Member of the Van der Mersch Family, Cornelis Troost, 1736

oil on panel, 29″ x 23″

Rijks Museum, Amsterdam

General Conyers is referring to a painting by Cornelis Troost (Dutch 1697-1750). Troost was one of the foremost Dutch painters of the eighteenth century. Living his entire life in Amsterdam, many of his early commissions were portraits. We show a portrait with a cello to honor General Conyers’ affinity for this instrument. Later Troost painted theater scenes and, during the 1740’s, many military subjects.