Watching Murtlock approach alone, Jenkins recalls a childhood memory that he shared with Moreland, a fear that a lone approaching figure was Apollyon, the fiend from The Pilgrim’s Progress; “a lively portrayal of the fiend in an illustration, realistically depicting his goat’s horns, bat’s wings, lion’s claws, lizard’s legs — the terror of that image, bursting out from an otherwise at moments prosy narrative, had imbedded itself for all time in the [Moreland’s] imagination. ” [HSH 216/233 ]

John Bunyan published the allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress in 1677. It has remained in print since then, appearing in multiple editions with many different illustrators, and is still widely read as a Christian lesson. Apollyon, the Destroyer, is the rebel angel who battles the hero Christian. Our narrator is a bit unreliable; Jenkins and Mortland’s memory does not quite match Bunyan’s description:

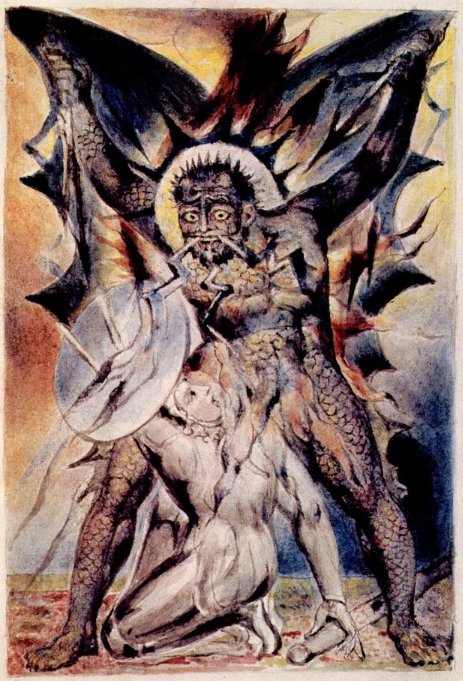

The Christian Fights Apollyon

The Pilgrim’s Progress, Plate 20

William Blake, 1824-1827

Watercolor

The Frick Collection

from Dark Figures in the Desired Country: Blake’s Illustrations to The Pilgrim’s … By Gerda S. Norvig, The Google Book project via Wikimedia Commons

We are not sure which illustration Jenkins and Moreland remembered from their childhoods. The illustration by William Blake (1824-1827) shows the terrifying Apollyon in frightening detail, with the scales worthy of pride, but Blake’s originals were watercolors and were not published with a text of the Pilgrim’s progress at the time (Norvig, 1993). The are currently in the Frick Collection, which exhibits them intermittently.

A number of Victorian illustrators took on the subject. H.C. Selous and M. Paolo Priolo’s version won a prize competition from the London Art Union but does not quite convey the full force of the terror that would stay in boys’ memories for the rest of their lives (for contemporary reaction, see The Spectator, 13 January 1844 ).

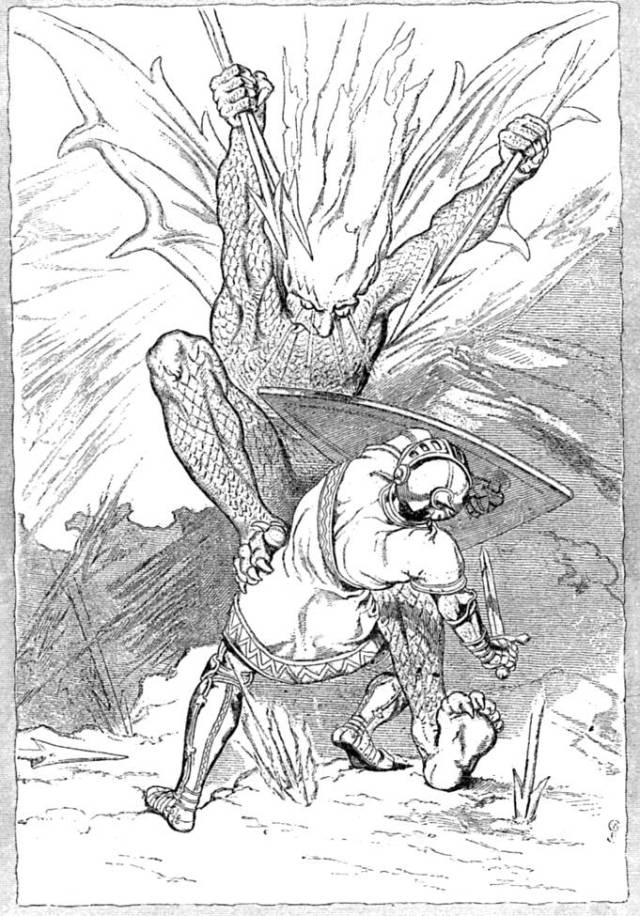

The Fight with Apollyon

Bunyan, John. The Pilgrim’s Progress . London, Edinburgh, and New York: Thomas Nelson and sons, 1887.

William Bell Scott

Wood block, 4 3/4 x 3 3/16 inches

image from the Victorian Web, scanned by George P. Landow

The illustration by William Bell Scott , published in 1887, catches Apollyon’s dynamic force, with plenty of claw and wing, but where are the horns?

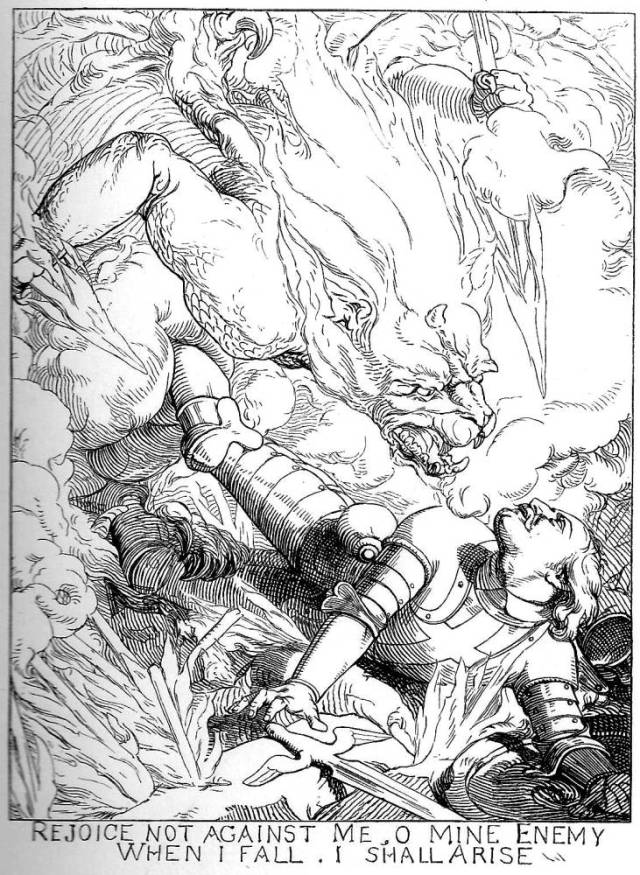

Christian Cast Down by Apollyon

from Illustrations to Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. London: Simpkin Marshall, 1864

Frederick Shields, 1864

Wood engraving, unsigned but probably by Joseph Swain,

4¾ x 4½ inches

from The Victorian Web, image scanned by Simon Cooke

The version by Frederick Shields shows Apollyon’s frightening fanged face but just a bit of claw and no wing to match Jenkins’ remembrance. There are many other Apollyons to consider, and new ones continue to appear, like an Apollyon in digital stained glass (Howard, 2014-2015). Perhaps imperfect memory, whether Powell’s, Jenkins’, or Mortland’s, inevitably prevents us from finding the exact fiend illustration that the boys recall; we suspect that like so many of Powell’s verbal images, the artwork that he describes is an olio of many works, mixed by his imagination.