Mr. Deacon’s Pre-Raphaelite Influences

A Buyer’s Market (BM) opens with our introduction to the inimitable Mr. Deacon––painter, antique dealer, and enthusiast of radical leftist causes. Long after Mr. Deacon’s death, Nick comes upon some of his canvases at an auction of items of dubious value near Euston Road: “All four canvases belonged to the same school of large, untidy, exclusively male figure compositions, light in tone and mythological in subject: Pre-Raphaelite in influence without being precisely Pre-Raphaelite in spirit: a compromise between, say, Burne-Jones and Alma-Tadema, with perhaps a touch of Watts in method of applying the paint. [BM 2/6]”

The Pre-Raphaelite influence Nick cites refers to the work of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, formed in 1848, and much championed by the Victorian critic John Ruskin. The founding generation of the Pre-Raphaelites included the English painters John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, and James Collinson. Their manifesto revolted against the soulless neo-classical formalism they perceived in the paintings of Raphael and his High Renaissance successors and argued for a return to the more deeply felt values that they attributed to medieval painting and to what they saw as realist painting. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s understanding of those terms––medievalism and realism––is different than that of audiences today, which is why we now perceive their paintings as having an exotic romanticism, more associated with fantasy than their creators might have expected.

- Pan and Psyche

Edward Burne-Jones, 1872-1874

Oil on canvas

sight: 25 5/8 x 21 in.

framed: 38 5/8 x 34 x 2 3/4 in.

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop, 1943.187

Edward Burne-Jones A.R.A. (1833-1898) was not in the first wave of Pre-Raphaelites though he is generally associated with them. Like Mr. Deacon, Edward Burne-Jones often painted mythological themes, but he did not share Mr. Deacon’s preference for exclusively male compositions. Burne-Jones pictorial goal was beauty, rather than story telling or moralizing. “I mean by a picture a beautiful, romantic dream of something that never was, never will be – in a light better than any light that ever shone – in a land no one can define or remember, only desire – and the forms divinely beautiful – and then I wake up, with the waking of Brynhild.” (from a letter to a friend quoted in Encyclopedia Britannica, 1911)

- Sappho and Alcaeus

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, R.A.

oil on panel, 1881

H: 26 x W: 48 1/16 in.; Framed H: 41 x W: 61 in The Waters Art Museum

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema R.A. (1836-1912) was a Dutch-born painter who settled in Britain in 1870 and remained there for the rest of his life, enjoying immense success as a painter of scenes from classical mythology and history. Alma-Tadema is not associated with the Pre-Raphaelites, but he shared their obsession with hyper-realist rendering of three-dimensional forms and added to it an astonishing command of linear perspective and the depiction of classical architecture. His particular brand of pictorial realism and his use of bright color seem more in the spirit of the Hollywood epics to come than in medievalist fantasies of his Pre-Raphaelite forebears.

George Frederic Watts (1817-1904) was a well-known Victorian painter and sculptor, sometimes associated with the Symbolist movement, and in some ways a painter more modern in spirit than either Burne-Jones or Alma-Tadema. He was adulated at the height of his career, in eclipse by 1930, and back in favor by 1960 (Powell, SPA... p. 219-220).Nick cites Watts in regard to his brushwork, which may refer to Watt’s somewhat looser paint handling, a greater willingness than is visible in either Burne-Jones or Alma-Tadema to let the movement of the painter’s hand become a part of the picture. And, in the accompanying painting, “Hope” (1886), Watt’s brushwork is sufficiently loose to allow the complimentary color of the underpainting to show through, a technique of optical color mixing more common in the work of the Impressionists than in that of more academic painters of the era.

Sidebar: Powell, Waugh, and the Pre-Rapaelites

The Awakening Conscience

William Holman Hunt, 1853

oil on canvas

The Tate, Britain

public domain photo from Wikimedia Commons

Evelyn Waugh is often paired with Powell in lists of the best British upper-class novelists of the mid twentieth century. We mention Waugh here to illustrate the connections of their set to the Pre-Raphaelites, whom Mr. Deacon missed so.

In Brideshead Revisited (1944), Waugh used a Pre-Raphaelite picture to punctuate a moral crisis in the affair between Juia and the painter Charles Ryder, who narrates the book:

‘Julia…have you ever seen a picture of Holman Hunt’s called “The Awakened Conscience”? ‘ He asked, then read her Ruskin’s description of the painting from Pre-Raphaelism

‘You’re perfectly right. That exactly what I feel,’ she replied.

Powell first met Waugh at Oxford in 1923, when Waugh was an aspiring artist and drew for The Cherwell. They remained friends until Waugh died in 1966. Waugh abandoned the idea of a career as a painter, but not his interest in art. His first publicly published book was on Dante Gabrielle Rossetti, an original member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. In an interview with Julian Jeb, April, 1962, for The Paris Review, Waugh describes how he happened to write the book in 1927:

I went to see my friend Anthony Powell, who was working with Duckworth, the publishers, at the time, and said, “I’m starving.” (This wasn’t true: my father fed me.) The director of the firm agreed to pay me fifty pounds for a brief life of Rossetti. I was delighted, as fifty pounds was quite a lot then. I dashed off and dashed it off. The result was hurried and bad. I haven’t let them reprint it again.

Waugh received this commission in part because he had already written P.R.B. An Essay on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood 1847-1854, which had been published privately the previous year. In that essay Waugh called The Awakening Conscience “the noblest painting by an Englishman. “ (TKBR, p. 130) Perhaps his judgment was influenced by Hunt’s marriage into the Waugh family.

In 1984, reviewing the catalogue of a Pre-Raphaelite exhibition at the Tate, Powell wrote that actually defining the Pre-Raphaelites is impossible; he summarized the evolution of their styles and the peaks and valleys of opinion about their art (SPA... p. 228-230). In another review, he cited Waugh’s changing opinion of George Watts between 1930 and 1960 as an example of how the reputation of these artists fluctuated (SPA …p. 219).

Mr. Deacon at Auction

Mr. Deacon reappears throughout A Buyer’s Market. The factual threads from which Powell wove Mr. Deacon are diverse. For example, as a teen Powell became friendly with Christopher Sclater Millard, the gay owner of a bookshop, a model for Mr. Deacon’s antique store. Nick’s parents had a long friendship with Mr. Deacon, but in reality, when Powell’s father learned the Millard had been in prison for his homosexuality, the elder Powell made his son stop seeing Millard. (TKBR p. 38-42). We will be paying more attention to Mr. Deacon as a commentary on art than on his politics or life style.

- Anthony and Cleopatra

Alma-Tadema 1883

private collection

photo in public domain from Wikipaintings

The opening scene in an auction room is apt, because one illustration of Time’s caprice is the fluctuating popularity of artists, particularly reflected in the price of their work. Mr. Deacon’s four canvases sell at the auction for a few pounds, no more than the value of the frames.

In 2010 Alma-Tadema’s Moses sold at auction for $35 million and in 2011 his Anthony and Cleopatra was gavelled at Sotheby’s for $26 million. Alma-Tadema showed Cleopatra at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1882-3. It was bought by Sir Joseph Robinson, whose collection was shown at the Royal Academy in 1958. It changed hands at a Southeby’s auction in 1962 for £2000 and at Christie’s in 1993 for £879,500. In Alma-Tadema’s day, his works were most valuable if the sale included the right to reproduce them as prints. In 1874 the price for a painting with these rights might have been as high as £10,000. More usual prices rose from £2,000 and £3,000 in the 1880s to about twice that by the early 1900s. However, prices for Victorian paintings collapsed in the early 1920s, and an Alma-Tadema could be had for a few hundred pounds. Prices were still that low when Powell published BM in 1952. Mr. Deacon was no Alma-Tadema, so his values were orders of magnitude less. We will have to wait until the final volume of Dance, set about 1971, to see if his prices recover.

Sketch of Antinous

Lansdowne Antinous. Marble, Roman Imperial artwork, ca. 130-140 AD.

Found at Hadrian’s Villa, 1769

The crown, nostrils, lips and torso have been restored. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge,

photo public domain from Wikimedia Commons

Two Sketches on Antinous

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925)

After the Antique

sketchbook page, 1869

The Fogg Museum of Art

A typical patron of Mr. Deacon was “a big iron man” from the Midlands who after visiting Deacon in London would return to Lancashire with “an oil sketch of Antinous, or a sheaf of charcoal studies of Spartan youth at exercise.” [BM 8/~4]

Antinous is sometimes called “the gay god.” He was a beautiful young Bithynian Greek boy, beloved by the Roman emperor Hadrian. When Antinous drowned in the Nile in 130, Hadrian gave him the extraordinary honor of deification. As a result there were many sculptures of his beautiful body, available for sketching by an Englishman on his Italian tour. By the late nineteenth century his homoerotic beauty was a passing metaphor in three of Oscar Wilde’s works and JA Symonds devoted a chapter to him in his Sketches And Studies In Italy and Greece (1879). Symonds quotes Shelley, who in his The Colliseum, A Fragment of a Romance, written about 1819, described statutes of Antinous as showing “eager and impassioned tenderness” and “effeminate sullenness of the eye.”

- Study of a Figure for Hell

John Singer Sargeant, c. 1900

Charcoal and stump on beige-laid paper, 18 7/8 x 24 1/2 in.,

Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

public domain from Wikimedia Commons

We have not found charcoal sketches of Spartan youth from Mr. Deacon’s era, so instead, we show here a charcoal nude by John Singer Sergeant, quite a bit more sophisticated than his teenage doodle of Antinous. To help imagine the Spartan youth, we show Degas’ version, even though Mr. Deacon would not have approved of Degas, at least not of his later work, but this painting of the Spartan girls urging the Spartan boys to wrestle illustrates an implication about Mr. Deacon’s patrons: we think the big iron man came to London for more than just art.

- Young Spartans Exercising

Edgar Degas, 1860

National Gallery, London - Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, Cubists, Surrealists

Impression, Sunrise

Claude Monet, 1872

Musee Marmotan Monet

public domain photo from Wikimedia Commns

Mr. Deacon “disliked the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists almost equally; and was naturally even more opposed to later trends like Cubism, and to the works of the Surrealists.” [BM 9/~5]

Mr. Deacon had strong historical precedent for his views. In April and May, 1874, thirty French artists who called themselves the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, Engravers, etc. exhibited their works for sale in a Parisian studio. Art critic Louis Leroy responded to the show with a scathing review in Le Charivari in the form of a dialogue. The following except about Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise seems to be the origin of the name Impressionists, which the group of artists used proudly by the time of their third exhibition in 1877.

“I glanced at Bertin’s pupil; his countenance was turning a deep red. A catastrophe seemed to me imminent, and it was reserved to M. Monet to contribute the last straw.

‘Ah, there he is, there he is!’ he cried, in front of No. 98. ‘I recognize him, papa Vincent’s favorite! What does that canvas depict? Look at the catalogue.’

‘Impression, Sunrise.’

‘Impression — I was certain of it. I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it . . . and what freedom, what ease of workmanship! Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape.'”

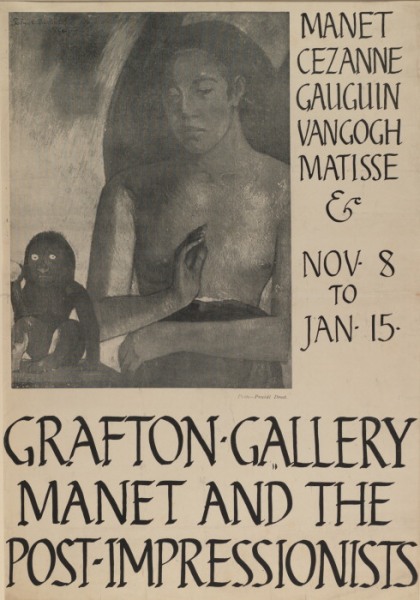

Poster for the Grafton Gallery from Art and Architecture website of the Courtauld Institute of Art

Despite this initial critical disdain, Impressionist painting grew in popularity and influenced younger artists. In 1910, a British painter and critic, Roger Fry organized a show of Manet, Cezanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Matisse, and others, for whom Fry coined the name Post-Impressionists. Fry and his contemporary critics touted these artists and by the 1920s they surpassed many of the popular late-nineteenth-century British artists as the height of fashion. This cultural shift was illustrated by Evelyn Waugh, Powell’s friend and competing novelist, providing another view of aristocratic Oxonian youth in the early 1920s; his narrator in Brideshead Revisited says. “in opinion I had made that easy leap, characteristic of my generation, from the puritanism of Ruskin to the puritanism of Roger Fry…”

Mr. Deacon, however, was not alone in his persistent distaste for Impressionism and almost everything that succeed it. Alma-Tadema shared this prejudice; John Collier, one of his pupils wrote, ‘it is impossible to reconcile the art of Alma-Tadema with that of of Matisse, Picasso, and Gauguin.”

When John William Godward (1861-1921), a disciple of Alma-Tadema, committed suicide, his suicide note reportedly said that the “the world was not big enough” for him and Picasso.

As late as 1949, Sir Alfred Munnings, a sporting artist in the tradition of George Stubbs, used his valedictory address as president of the Royal Academy for a diatribe against Picasso, Matisse, and their ilk. (see Chew, The Painter who Hated Picasso, Smithsonian Magazine, October, 2006.)

Art movements are referenced repeatedly and knowledgeably in Dance. We will get to Cubism and Surrealism later. Jenkins continues describing Mr Deacon: “Nature had no doubt intended him in some manner to be an adjunct to the art movement of the Eighteen-Nineties.” Many movements competed and elided in late nineteenth century Britain: Pre-Raphaelism, Aestheticism, Symbolism, Arts and Crafts, Realism, Art Nouveau, and so on; there was no single “Art Movement of the Eighteen-Nineties.” By his imprecision, the Narrator is emphasizing how isolated Mr. Deacon was from prevailing styles. “Somehow Mr. Deacon had missed that spirit in his youth, a moral separation that perhaps accounted for a later lack of integration.” [BM 9/~5].

Puvis de Chavannes and Simeon Solomon

Nick says of Mr. Deacon: “Puvis de Chavannes and Simeon Solomon, the last of whom I think he regarded as his master, were the only painters I ever heard him speak of with unqualified approval.” [BM 9/5]

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898) was a prominent French painter of the mid nineteenth century, known as a Symbolist and as co-founder of the Societe Nationale des Beaux-Artes. As a painter, he rejected realism in favor of a synthetic idealism, and he transformed traditional linear perspective into an expressive tool by routinely collapsing or compressing space in his images. He was radical for his time and influenced many strands of the development of Modernism (see Musee d’Orsay on his work The Poor Fisherman). We have chosen to show Le Travail, because it almost satisfies Mr. Deacon’s preference for “exclusively male figure compositions.” Like Alma Tadema and other British nineteenth century painters whom Deacon did not despise, Puvis de Chavannes fell from fashion early in the twentieth century.

Love in Autumn

Simeon Solomon, 1866

photo public domain fromWikimedia Commons

Simeon Solomon (1840-1905) first exhibited at the Royal Academy at age 18. His early paintings share the flamboyance and mastery of his Pre-Raphaelite mentors Rossetti, Burne-Jones, and Millais; his later work is more intimate and favors feeling over bravura draftsmanship and paint handling. Solomon’s themes drew heavily on his Jewish heritage and the Old Testament. He became friendly with Swinburne, whose interests in classicism and erotica, helped move Solomon toward Aestheticism, “art for art’s sake.” His celebrity grew until 1873, when he was arrested for attempted sodomy at a public urinal in London. Later, he was arrested again for sodomy in Paris. Although he continued to paint, he fell from public attention and lived a life of alcohol abuse and poverty, until he died at St. Giles’s Workhouse in Bloomsbury. Presumably, his lack of official approval and bohemian life style enhanced Mr. Deacon’s attraction to him.

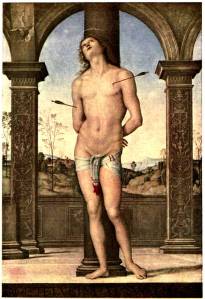

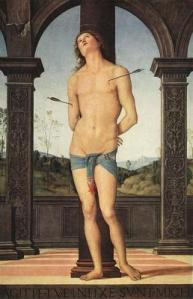

St. Sebastion

Pietro Perugino,

The Louvre

Plate 2 from Brinton, Perugino, project Gutenberg ebook

St. Sebastian

Pietro Perugino

oil on wood, 170 x 117 cm, after 1490

The Louvre

photo public domain from Artmight.com

St. Sebastian by Pietro Perugino

At the Louvre in about 1919, Nick and his parents run into Mr. Deacon, who has stooped over, magnifying glass in hand , to examine closely a painting of St. Sebastian by Pietro Perugino ( c. 1446-1524). [BM 14/10] Sebastian was a Roman centurion martyred about 286 for his conversion to Christianity. He has been painted many times with his characteristic iconography, wounded by arrows, tied to a post, but he was actually clubbed to death. Perugino painted St. Sebastian at least six times. Mr. Deacon, “showing an unexpected grasp of military hierarchy — at least of an obsolete order,” commented that the real St. Sebastian, as a centurion, must have been older and more rugged than the youth shown by Perugino.

Perugino was one of the masters of the Quattrocento. His frescoes decorate the walls of the Sistine Chapel by commission of Pope Sixtus IV. He was among the first to paint with oil.

Mr. Deacon claimed that other pictures in the Louvre, attributed to Raphael, were actually Peruginos. Misattribution of paintings is an issue that resurfaces later in Dance. Here we suspect that Mr. Deacon was showing his contrarian streak rather than his connoisseurship. In the 1490s Raphael, an orphan, was placed by his relatives in Perugino’s workshop in Florence. His apprentice’s brushstrokes very likely grace more than one Perugino. In 2012 the Alte Pinakothek in Munich mounted an exhibit Perugino: Raphael’s Master, which in part addressed the question of why for the last half millenium Perugino’s reputation has been in the shadow of his contemporaries: Michelangelo, Leonardo, and Raphael. Vasari (Lives of the Painters, 1568) praised Raphael and denigrated Perugino:

“I will not refrain from saying that it was recognized, after [Raphael] had been in Florence, that he changed and improved his manner so much, from having seen many works by the hands of excellent masters, that it had nothing to do with his earlier manner; indeed, the two might have belonged to different masters, one much more excellent than the other in painting. ”

During his lifetime Perugino’s peers, including Raphael’s father, had called him the ‘divine painter.’ Mr. Deacon seems to have a natural affinity with artists whom history has devalued.

Montmartre in Whistler’s Time

Nicholas, still remembering Mr. Deacon at the Louvre in about 1919, says that Mr. Deacon bemoaned the “‘Americanisation’ of the Latin Quarter,” and said, “I sometimes think of moving up to Montmartre, like an artist of Whistler’s time.” [BM 17/ ~13]

Portrait of Whistler with a Hat

James McNeill Whistler, 1857-1859

The Freer Gallery of Art and Arthus M. Sackler Gallery (with permission)

Oil on canvas

H: 46.3 W: 38.1 cm

James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) was born in America, spent part of his childhood in Russia, attended West Point, and did his best known painting in Britain; however, he did live and study in Paris from 1855 until about 1859 and later returned there from time to time. His method of study included copying paintings at the Louvre; this self portrait from his Parisian student days strongly reflects the influence of the Rembrandts that he studied in the Louvre. He lived at this time in the Latin Quarter and was often penurious, selling few paintings. In 1859 he moved to London .

Montmartre developed as a hillside village of farms and windmills, north of central Paris. The village became urbanized in the second half of the nineteenth century and began to attract artist’s studios. Whistler, returning to Paris in 1861, rented a studio there. However, the heyday of Montmartre, vying with the Latin Quarter as the artistic center of Paris, was really in the 1880’s and 90’s when artists like Toulouse-Lautrec, Van Gogh, Degas, and Renoir painted there. (Myers, Nicole. “The Lure of Montmartre, 1880–1900”. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000). We suspect that Deacon was not yearning for the flamboyant Montmartre of Toulouse-Lautrec but, rather, knew this history of Whistler’s time and was nostalgic for the 1860s before bohemian became chic. As for Whistler, when he moved back to Paris in 1892, he settled in the more aristocratic Faubourg St. Germain.

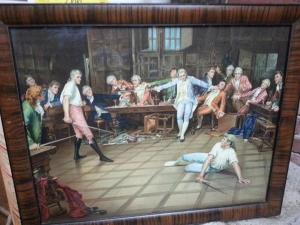

The Boyhood of Cyrus

The first time that Jenkins actually sees a Deacon canvas is when he visits the Walpole-Wilson house in Eaton Square about 1928. “The canvas, comparatively small for a ‘Deacon,’ evidently not much considered by its owners, had been placed beyond the staircase above a Victorian barometer in a polished mahogany case. ” [BM 19/15]

Victorian Banjo Barometer, ca, 1860

Victorian Banjo Barometer, ca, 1860

mahogany veneer

It is amazingly easy to find a a photo to illustrate that barometer, but impossible, of course, ever to see the Deacon canvas of The Boyhood of Cyrus. Peter Campbell (London Review of Books 28:33 1/28/2006) writing on an exhibit at the Wallace Collection devoted to Powell, put it well:

“When both painter and paintings are fictional it is harder to imagine the pictures. The look of Edgar Deacon’s Boyhood of Cyrus must be worked out from the comparisons on offer: the Pre-Raphaelites, Simeon Solomon (whose soft-faced youths are perhaps the most suggestive parallel) and Puvis de Chavannes. It’s a mistake to match real and fictional art too quickly, just as it’s a mistake to look for the real-life originals of a novelist’s characters, but there’s no harm in identifying real elements that – like the cut-outs and bits of print Powell pasted onto screens and into scrapbooks – can be used to round an invention out.”

To start imagining the Boyhood of Cyrus, we looked at Puvis de Chavannes’ Ludus Pro Patria. The bucolic locale for these patriotic games, the setting in antiquity, and the partially clad figures all fit what we know of Mr. Deacon’s style.

Ludus Pro Patria

Ludus Pro Patria

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, 1883

oil on canvas

H: 44 11/16 x W: 77 9/16 in.

The Walters Art Museum

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

We then guessed that Mr. Deacon’s vision of the youth of Cyrus the Great, sixth century B.C. king of the Persian Empire, would have come from Herodotus, who related that at age ten Cyrus was “was playing on the road with other [children] of his age; and playing, the children chose him to be king over them, although he was nominally the son of a herdsman. And he appointed some of them to build a house, others to be spearmen, and of course, one of them to be ‘the Eye of the King,’ assigning tasks to each of them separately. One of these children … did not do the task assigned by Cyrus. He therefore ordered the other children to seize him. The children obeyed and Cyrus handled the child very roughly, and whipped him. ” (Tales from Herodotus: VIII. Story of Cyrus the Great, translated at metaphrastes.wordpress.com) That this founder’s myth is of dubious truth is irrelevant to our imagination. We looked back at Ludis Pro Patria, replacing the figures with young boys, obeying the future king.

We are not the first to alter a Puvis de Chavannes painting for a little fun. His The Sacred Grove (Le Bois sacré cher aux arts et aux muses), visible at the Art Institute of Chicago, won a prize at the Salon of 1884. Toulouse-Lautrec, age 20, saw the exhibition and rushed with his friends to ape the style in a large painting, thirteen feet long and six feet high, replacing the nymphs with pictures of himself and acquaintances and adding a number of anachronisms and sight gags. This parody of Puvis de Chavannes was long little known, held in private collections; Henry Pearlman brought it to the US in 1953, but it was first loaned by the Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation to the Princeton Art Museum in the 1970s. Powell probably did not know the parody when he wrote BM, but it is in the spirit of his humorous depiction of Mr. Deacon.

The Sacred Grove

The Sacred Grove

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1884 photo by Bruce M White

The Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection

at the Princeton University Art Museum

As for Mr. Deacon himself, the widening chasm that separated his sensibilities from those of Toulouse-Lautrec and myriad other pioneers of Modernism can be glimpsed by comparing Ludus Pro Patria with Degas’ Young Spartans Exercising, reproduced in our post called “Sketch of Antinous.” Degas’ painting is the earlier, but forward-looking in its lack of sentimentality; Puvis de Chavannes’ later treatment of a similar scene is filled with nostalgia.

Victorian Monuments

Statue of Achilles

Sir Richard Westmacott

Hyde Park, Londn

photo by Barry Shimmon

from Wikimedia Commons by Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 license.

On a warm Sunday in June, a walk in Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens kindles Jenkins infatuation with Barbara Goring. “That was the last day for many months that I woke up in the morning without immediately thinking of her [BM 22/18].” By chance, he met her and Eleanor Walpole-Wilson near the Achilles statue, an 18 foot tall bronze that rises another 18 feet on a plinth of Dartmoor granite. It was designed by Sir Richard Westmacott and sculpted in 1822, when Victoria was three years old. It honors the Duke of Wellington; the bronze for the statue was from cannons that the Duke captured in battle.

The Albert Memorial

Architect: Sir George Gilbert Scott

Designed: 1872

Completed: 1876 (unveiled by Queen Victoria)

Height: 180 Feet

photo from the Victorian Web

Detail from The Painters, The Frieze of Parnassus on the Albert Memorial

Henry Hugh Armstead

photo by George P. Landow

The Victorian Web

Detail of Asia

The Continents: Asia by John Henry Foley (1818-1874). Completed 1876; restored 2000. Marble. Albert Memorial

photo by George P. Landow

The Victorian Web

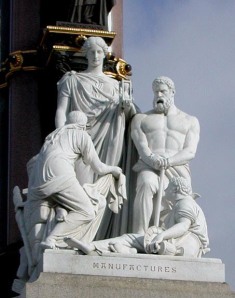

They walked through Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens, a little over a mile to the Albert Memorial, completed in 1876, designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott. The monument, rising about five times higher than the top of Achilles’ head, is a compendium of Victorian sculpture. The Queen approved the artists and their designs. The walkers inspected the figures of Arts and Sciences, 169 of whom circle the memorial in the Frieze of Parnassus. Eleanor says something about the muscular bearded manufacturer, causing Barbara to break into laughter. As they come down the steps near the group symbolizing Asia, Barbara stumbles and briefly supports herself on Jenkins’ arm, giving him a delayed emotional frisson.

The Useful Arts: Manufactures

Henry Weekes

Completed: 1876

Granite?

The Albert Memorial

Photograph by George P. Landow 1999

The Victorian Web

Are these massive monuments mentioned just to orient us geographically? Both the Manufactures and Asia are on the southeast corner of the monument, so it is natural that the walkers should see these together.

Powell rarely misses an opportunity to let a work of art–– actual, fictional, or a composite of the two––enrich our understanding of his characters and their milieu. Here, is he guiding us to nineteenth century associations, thoughts of Victoria and her Empire? Should we remember that the Achilles statue caused a stir as the first nude statue in London (see the cartoon from 1822 of Wilberforce using his hat to make up for a fig leaf that some thought too small.)? Should we ponder why Powell mentions the Manufacturers, rather than Commerce, Agriculture, or Engineering? Why attend to the Asian Bedouin’s “hopeless contemplation of Kensington Gardens…” while ignoring Africa, America, and Europe, even though Africa was Powell’s personal favorite (SPA….. 244)? For now we will enjoy the tale of young love and let others decide whether to try to read this more closely.

Lavery’s portrait of Lady Walpole-Wilson

At the home of the Walpole-Wilsons, Nick is accosted by Sir Gavin, who, “no doubt because he prided himself on putting young men at their ease, drew my attention to another guest . . . . This person was standing under Lavery’s portrait of Lady Walpole-Wilson, painted at the time of her marriage, in a white dress and blue sash, a picture he was examining with the air of one trying to fill in the seconds before introductions begin to take place, rather than on account of a deep interest in art. [BM 33/28]”

The Lavery whom Nick mentions is Sir John Lavery R.A. (1856-1941), a Belfast-born society painter active in London after the First World War. Lavery received his art training in Glasgow and became associated with the Glasgow Boys’ brand of pastoral realism, but his bread-and-butter career consisted of commissioned portraiture of rich and prominent English patrons. In his later life, Lavery returned to Belfast and was active in the Irish nationalist movement. Despite his attempts to learn from his friend Whistler, his society portraits today seem somewhat bland and facile, though undoubtedly competent, and his name has faded from view since his death.

Lady Evelyn Farquhar

Sir John Lavery, 1907

photo public domain from The Athenaeum

This reproduction of Lavery’s portrait of Lady Evelyn Farquhar (1907) may give an idea of the portrait of Lady Walpole Wilson that Powell envisions hanging above Widmerpool as Nick’s attention is called there by Sir Gavin.

The Boyhood of Widmerpool

Jenkins, unexpectedly, sees Widmerpool at the Walpole-Wilson’s. “Just as the first sight of the Boyhood of Cyrus … had brought back memories of childhood, the sight of Widmerpool called up in a similar manner — almost like some parallel scene from Mr. Deacon’s brush entitled Boyhood of Widmerpool — all kinds of reflections of days at school [BM 34/30].”

We have gone from real pictures by real artists (The Boyhood of Raleigh), to fictional pictures by real artists (Lavery’s Lady Walpole-Wilson), to fictional pictures by fictional artists (The Boyhood of Cyrus). Now we have the absurd task of imagining a painting that a fictional artist did not paint. The task is comedic, not only because the painting does not exist, but also because Boyhood paintings are reserved for the genesis myths of heros, Raleigh or Cyrus or King Alfred or Abraham Lincoln; whereas, we know Widmerpool only for his remarkable ambition coupled with social ineptitude. So, is the Boyhood of Widmerpool just a joke, or does it forewarn us that we are learning about the youth of the antihero of the Dance?

The Haig Statue

Earl Haig Memorial

Whitehall, London

Alfred Hardiman, 1936

photo by R. Sones from Wikimedia Commons by Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 license

At a dinner party at the Walpole-Wilson’s, Widmerpool offers a new subject of conversation: “There does not seem any substantial agreement yet on the subject of the Haig statue….Did you read St. John Clarke’s letter? [BM 45/39]” For Widmerpool, who had little interest in art, to introduce the topic shows how widespread interest was in the statue, and in the ensuing dinner conversation, the diverse opinions are more about the goals than about the aesthetics of the monument. “‘The question, to my mind,’ said Widmerpool, ‘is whether a statue is, in reality, an appropriate form of recognition for public service in modern times.'”

Field Marshal Earl Haig, Commander-in-Chief of the British Armies in France 1915-1918, died in January, 1928 and within a month Parliament authorized a memorial statue. Alfred Hardiman won the commission for the memorial in competition with Gilbert Ledward and William Macmillan, but controversy surrounded the project from the start, especially when Hardiman’s model, displayed in 1929, showed Haig astride a classical equine statue in the Roman tradition, rather than a more realistic model of his own horse. Hardiman made a second, somewhat more realistic model, but never succeeded in quieting all his critics.

The Spearman

Ivan Mestrovic, 1928

Chicago

photo by Einar Einarsson Kvaran from Wikimedia Commons by Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 licence

In the conversation at the dinner party, Lady Anne Stepney says that the commission should have gone to Mestrovic. She was not alone in this opinion. The Croatian sculptor, Ivan Mestrovic (1883-1962), a disciple of Rodin, had combined an equestrian monument and national shrine in his model for the Temple of Kosovo It was first shown at the Serbian Pavilion at the International Exhibition in Rome in 1911 In 1915 the model was displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and young British sculptors began to emulate Mestrovic. The Temple of Kosovo was never completed. The Spearman shows how he might have sculpted Haig’s steed.

This dinner table discussion creates some ambiguity for dating the action in BM. Many of the events in this volume suggest that it takes place in 1928, but a conversation like this about the Haig statue would have been much more likely to occur after Hardiman showed the model in 1929.

The monument was finally unveiled in 1937; the unveiling can still be seen on archived newsreels. This did not end all the controversies, but they are still not primarily artistic. Even now, some have vilified Haig’s leadership, accusing him of sacrificing his men, and urging removal of his memorial.

Talk of Botticelli

Adoriation of the Magi

Sandro Botticelli ca. 1478-1482

tempera and oil on panel

framed 39 X 52 inches

The Andrew W. Mellon Collection

The National Gallery of Art

At the dinner party at the Walpole-Wilson’s, Nick first meets Lady Anne Stepney, the unruly younger sister of Peggy Stepney, Stringham’s sometimes-wife. Pressed for conversational gambits, Nick reports “We talked for a time of Botticelli, the only painter in whom she appeared to feel any keen interest . . . . [BM 52/46]”

Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510) was a hugely successful Florentine painter, the student of Fra Fillipo Lippi, but perhaps more widely known by today’s audience than is his teacher. Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus and Primavera are among the most familiar icons in the Western canon of painting, recognizable even to viewers with little knowledge of art history. Somewhat less well-known are the beautiful religious scenes from his later career, represented here by The Adoration of the Magi, now in the National Gallery in Washington D.C.

Botticelli’s fame declined after his death, and he was largely ignored until the Pre-Raphaelites took him up, at the end of the 19th century, as an exemplar of the lyrical realism they championed. By the time of the Walpole-Wilson’s dinner party between the World Wars, Botticelli’s paintings in the Uffizi were once again necessary stops on anyone’s grand tour of Europe. Hence, Lady Anne Stepney’s unwillingness to venture beyond Botticelli in her conversation with an art book publisher speaks less of her connoisseurship than of her truculence as a dinner partner.

Van Dyck

Nick travels with the Walpole-Wilsons to a ball at the London home of the Huntercombes. “Hanging at the far end of the ballroom was a Van Dyck––the only picture of any interest the Huntercombes kept in London––representing Prince Rupert conversing with a herald, the latter being, I believe, the personage from whom the surviving branch of the family was directly descended.” (BM 58)

Anthony Van Dyck (1599-1641) was the Flemish protégé of Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), to whom he was apprenticed as a young painter in Antwerp, and who recommended the promising Van Dyck to Charles I of England, a discerning patron of the arts. Six years in Italy afforded Van Dyck the exposure to Veronese and Titian that fueled his unique synthesis of draughtsmanship, color and Baroque composition. In 1632 Charles I lured Van Dyck to London and retained him as court painter, in which role he enjoyed immense success as a portraitist and painter of religious and allegorical scenes. Van Dyck’s elegant and flattering portraits are often credited with forming the foundation of the great age of British portraiture of the later seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The Prince Rupert portrayed in the Huntercombe’s Van Dyck is Prince Rupert, Count Palatinate of the Rhine (1619-1682), the nephew of Charles I, who also made Rupert the first Duke of Cumberland. There is a Van Dyck portrait of Rupert in the National Gallery in London, but we can find no painting of Rupert conversing with a herald. Powell’s apparent invention here suggests the eagerness of the Huntercombs and other old families, not otherwise in possession of distinguished art, to display for company the distinguished antiquity of their lineage.

Reproduced here is Van Dyck’s double portrait of Rupert (on the right) with his brother Charles, with whom he is most decidedly not conversing. This painting exemplifies many of Van Dyck’s hallmark portrait characteristics: extreme, almost witty, elegance in the pose of the faces and hands; exquisite attention to the textures and colors of the costumes, interior architecture churned with a Baroque sense of movement in the draperies and shadows (as contrasted with the stasis and solidity of High Renaissance interiors), and a view to a brooding, proto-Romantic landscape.

The Frog Footman

Rosy Manasch is talking to Jenkins, while sitting out a dance. Suddenly, Widermerpool stumbles over her foot on his way upstairs.

“‘I know who he is!’ She said, when he had apologized and disappeared from sight with his partner. ‘He’s the Frog Footman.'” [BM 67/61]

This allusion in the casual conversation of twenty-somethings in the later 1920s needed no citation, anymore than a gen-Xer would need to footnote a reference to Elmo or Papa Smurf. Everyone at the party would be familiar with Sir John Tenniel’s illustrations for the first edition of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). This is only one of many Tenniel drawings mentioned in Dance.

What frog-footman traits did Rosy see in Widermerpool — the arrogant upraised chin, the bulging eyes, the failure to look directly at his interlocuter, the preposterous formal dress? Like the frog footman, he certainly jumps out from the human crowd.

Murillo’s School

In the supper room at the Huntercombes’ ball, Nick finds himself at a table with Barbara Goring and Widmerpool, “in the corner underneath a picture of Murillo’s school in which peasant boys played with a calf.” (BM 73/67) The Murillo in question is Bartolome Esteban Murillo (1617-1682), one of the most influential painters of the Spanish Baroque period.

Murillo is a favorite son of Seville, and the term “school of Seville” is virtually synonymous with “school of Murillo.” He is most often identified with the dreamy, ornate religiosity of his most famous paintings, such as this “Immaculate Conception of the Venerable Ones” of 1678, now in the Prado.

Somewhat less well-known than Murillo’s religious paintings are his many scenes contemporary peasants, largely done early in his career. These are unsentimental, non-judgmental windows into the life of the streets in 17th century Seville, and they are part of a social realist strain of Spanish painting famously found in the work of Velasquez and later in that of Goya. In the last half of the 19th century that social realism was rediscovered and repurposed by Eduard Manet and other French modernists, who rekindled widespread interest in the masters of the Spanish Baroque, Murillo included.

We can find no specific examples of a painting of boys playing with a calf by Murillo or a painter in the school of Murillo, but this reproduction of Murillo’s “Beggar Boys Eating Grapes and Melon” might give an idea of the unromantic character of these genre paintings. Perhaps this is another of Powell’s inventions of a fictitious work by an historical artist, of which several examples exist in Dance. In any case, we could not help noticing that Powell’s phrase “boys playing with a calf” prefigures the imminent fate of that calf Widmerpool in the hands of Barbara Goring.

Quadriga’s Horses

- The Quadriga atop the Wellington Arch

Hyde Park Corner

London, U.K.

photo from Wikimedia Commons

The final punctuation of Jenkins infatuation with Barbara Goring occurs near another monument, a few hundred yards from the Achilles statute where it began. Walking with Widmerpool, who is describing his own feelings for Barbara to Nick’s dismay, they arrive at Grosvenor Place, “in sight of the triumphal arch, across the summit of which, like a vast paper-weight or capital ornament of an Empire clock, the Quadriga’s horses, against a sky of indigo and silver, pranced desperately towards the abyss.” [BM 89/82]

- Empire Clock, ormulu, showing Minerva driving the chariot of Diomedes, ~1810,

photo from Gavin Douglas Fine Antiques Ltd.

Empire clocks, which orginated during the reign of Napoleon, are mantel clocks incorporating elaborate sculptures, often of ormulu bronze. “Pendules au char” are a variety of Empire clocks with chariot sculptures. In October, 2013, we found one for sale on eBay with an elegant clock face forming the wheel of the chariot.

Nick identified the Empire-clock-type ornament as a quadriga or chariot pulled by four horses, a traditional symbol of victory. Examples are numerou,s including sculptures topping the Bradenburg Gate in Berlin (1793), the Arc de Triomphe in Paris (1815), others in St. Petersburg, Moscow, Rome, Munich, Brussels, and so on. The quadriga sculpture at Hyde Park Corner sits atop the Wellington Arch, completed in 1827 to commemorate Wellington’s victory over Napoleon. This Quadriga, reputedly the largest bronze sculpture in Europe, was designed by Adrian Jones in 1912, and shows the Angel of Peace driving the Quadriga of War, which is led by a small boy.

Peter the Hermit

Preparing to part from Nick in Grosvenor Place, Widmerpool clumsily backs into an angry young woman––our first introduction to the redoubtable Gypsy Jones––and an elderly male companion, whom Nick gradually recognizes as Mr. Deacon. “He looked much the same, except that there was now something wilder––even a trifle sinister––in his aspect: a representation of Lear on the heath, or Peter the Hermit, in some nineteenth-century historical picture, preaching a crusade.” [BM 91/84]

Peter the Hermit is the historical epithet given to Peter of Amiens, a French monk of the eleventh century AD who was reputed to have lived for a time as a hermit. Legends identify Peter the Hermit as the instigator of the First Crusade against the infidels in the Holy Land, but reliable accounts assign that role to Pope Urban II. Peter was, nevertheless, an uncommonly charismatic preacher, and when he was moved to join the crusaders against the Turks, he gathered with him a huge following of peasants as he marched across Europe toward Jerusalem in 1096. His fortunes in battle were no match for his stirring rhetoric, however, and he was lucky to return alive to Liege (in present-day Belgium), where he founded a monastery at Neufmoutier and died in 1115.

If Peter the Hermit’s story is muddled by legendary accounts, his actual appearance is even more obscure; he is represented quite variously in visual lore through the ages. Nick’s memory is likely drawn to something like the image represented here, which is reprinted from a nineteenth century history text and provides a bit of the wild and hoary aspect Nick senses in Mr. Deacon’s appearance.

An Unsatisfying Derain

At Mrs. Andriadis’ party, Jenkins sees Sir Magnus Donners standing “beneath an unsatisfying picture in the manner of Derain [BM 144/136 ]”

Andre Derain (1880-1954) was a French artist, present at the birth of Fauvism, friendly with Picasso and Matisse, inventive in his London cityscapes, but later reverting to neoclassicism. Which of these manners of Derain would be displayed to Jenkins dissatisfaction? As usual, we do not even know if Powell is thinking of a specific painting, imagining a fictious painting, or simply inducing us to think about the evolution of Modernism.

Derain’s reputation has waxed and waned. “Of all the major figures in the Ecole de Paris, André Derain’s reputation has sunk into the deepest trough. It is doubtful if it will ever again stand as high as it did between the two World Wars. (Edward Lucie-Smith, Lives of the Great 20-th Century Artists)”

Derain painted The Bathers in 1907. Derain and Matisse are credited with leading the Fauvist movement, named in a review of the Salon d’Automne exhibit in 1905. The Bathers has characteristically Fauvist wild brush strokes and dissonnant colors.

In 1906 the Parisian art dealer Ambroise Vollard sent Derain to London to paint views of the city. Charing Cross Bridge is just one of the 30 canvases in this series; these are some of his most appreciated works (see for example the exhibit Andre Derain: The London Paintings, 2005-6, The Courtauld Institute). He continued his Fauvist brush work but used welcoming energetic colors, producing a lighter, more vibrant view of London than in earlier famous cityscapes, like those of Monet and Whistler.

Derain served in World War I. After the war, his painting was more convservative. He went to Italy in 1921 for the Raphael centenary, and in both his writing and his painting paid homage to classical artists. He still won awards; his first solo exhibit in London was at the Lefevre Gallery in 1928, where the painting might have been acquired.

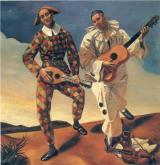

- Harlequin and Pierrot

Andre Derain 1924

Musee de L’Orangerie, Paris

photo from Wikipaintings by fair use

work copyrighted in France

Derain’s later work had a mixed critical reception; for example, in 1931 Jacques-Emile Blanche wrote of this part of Derain’s career: “Youth has departed: what remains is a highly cerebral and rather mechanical art.” (from Andre Derain: Pour ou Contre quoted in “Derain, André” The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. Ed Ian Chilvers. Oxford University Press 2009 Oxford Reference Online. ) For example, his Harlequin and Pierrot (1924) shows a nostalgic sentimentality. By this time, Derain’s friend Picasso had become much less representational and more adventuresome in his series of Harlequins. We welcome our readers’ speculations about which style of Derain would have dissatisfied Jenkins.

Derain died in 1954, so his works are still under copyright in France; therefore, we show only thumbnails and encourage our readers to follow the links to better reproductions of the works.

Adam and Eve Leaving the Garden of Eden

- Adam and Eve Driven from Paradise

James Tissot

http://www.jamestissot.org

Gouache on board, 8 7/8 x 12 7/16 in. (22.6 x 31.7 cm)

The Jewish Museum, New York

When Sir Magnus and Baby Wentworth enter the room together, Jenkins is struck by the appearance of this usually beautiful woman: she had an ‘almost hang-dog air;’ her ‘features had lost all gaiety and animation;’ she appeared ‘sulky,’ ‘almost awkward.’ [BM 147/] She reminds Jenkins of an painting of Adam and Eve leaving Eden.

Adam and Eve have been painted many times and are familiar to all; the scene is cinematically vivid in Powell’s witty prose, so why should we bother to blog about paintings that Powell was not describing? First, Jenkins is reminded of modern Biblical paintings, so this gives us an opportunity to learn more about other artists whose work Powell must have known. Second, we welcome the opportunity to ponder the end of the paragraph: “I almost expected them to be followed through the door by a well-tailored angel, pointing in their direction a flaming sword.”

Jenkins was imaging a modern painting, not one ‘in Mr. Deacon’s vernacular.’ He clearly was not thinking of the work above by James Tissot. We show it because, like Baby Wentworth, this Eve is small with dark curly hair and a face expressing her dismay.

Tissot (1834-1902) was born in Nantes and started painting in France, but anglicized his name from Jacques-Joseph to James. He built a career as a society painter. Proust says that Tissot’s La Cercle de la Rue Royale (1868), showing members of the Paris Jockey Club, includes his friend Swann (Karpeles, p237). Tissot spent his later career in Britain. When his beloved mistress Kathleen Newton died, he became more devoutly Catholic and often painted religious themes. A contemporary and friend of Alma-Tadema, Degas, and Whistler, Tissot was most akin stylistically to the first of these.

- Zacharias and Elizabeth

Stanley Spencer, 1913-4

oil and graphite on canvas

Tate Britain

© Estate of Stanley Spencer. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2002

One painter from Jenkin’s era who showed Biblical figures in modern settings is Sir Stanley Spencer (1891-1959). In the Zacharias and Elizabeth, he shows Archangel Gabriel telling Zacharias that his wife will bear a child from God. Spencer typically set his twentieth century versions of biblical scenes in his native village of Cookham, along the Thames. However, neither Spencer nor other modern biblical painters whom we have sampled, like Chagall, Rouault, or Joseph Epstein, depict their angels with quite the well-tailored look that Jenkins imagined.

Could Powell, by referring to that anachronisitic angel, be offering a sly reductio ad absurdum critique of those who would translocate the Bible to the twentieth century? Clearly not; Powell knew that artists for millenia have been transposing Biblical scenes into their local settings. Even Tissot, who went to the Holy Land so that he could paint the Bible authentically, reportedly paid homage to Kathleen Newton with Eve’s face and mistakenly modelled his Biblical headresses on Greek busts.

We are left to wonder whether Jenkins fantasizes that the avenging angel, dressed for the party, is there only for Sir Magnus and his mistress or is surveying the whole exotic crowd of men in white tie with their beautiful bejeweled women.

Canaletto, Piranesi, Hubert Robert, and Pannini

After Mrs. Andriadis’ party and an exhaustingly long night out, Nick returns to the neighborhood of his shabby flat in Shepherd Market, gentrified today but then a precinct of “seedy glory” in his eyes. In reality, the walk through Mayfair is only a few minutes, but Powell makes it seem like a journey through time. In a sweeping passage evoking the romantic beauty of sunrise over this ruinous quarter, Powell invokes no fewer than four eighteenth-century artists to help paint the scene:

“Now, touched almost mystically, like another Stonehenge, by the first rays of the morning sun, the spot seemed one of those clusters of tumble-down dwellings depicted by Canaletto or Piranesi, habitations from amongst which arches, obelisks and viaducts, ruined and overgrown with ivy, arise from the mean houses huddled together below them . . . . As I penetrated farther into the heart of that rookery, in the direction of my own door, there even stood, as if waiting to greet a friend, one of those indeterminate figures that occur so frequently in the pictures of the kind suggested—Hubert Robert or Pannini––in which the architectural subject predominates.” [BM 161-2/153-4]

Canaletto is the name by which we now know the Venetian painter Giovanni Antonio Canal (1697-1768), famous for his majestic depictions of Venice, at once panoramic and filled with local incident and detail. Powell alludes to the way in which Canaletto’s admiration for Venice’s architectural splendors blends seamlessly with his attention to the squalor of everyday life in La Serenissima. Canaletto’s paintings were highly prized by English visitors to Italy, and many Canalettos found their way into the great British collections. Late in his career Canaletto moved to England, where he painted many scenes of London and the great houses in the surrounding countryside, but his genius seems not as well suited to this terrain as to his native city, and the English paintings are not among his most highly regarded.

The Stonemason’s Yard, reproduced here, gives a sense of Canaletto’s proto-Romantic pairing of the humble and the sublime that so moves Nick as he approaches Shepherd Market.

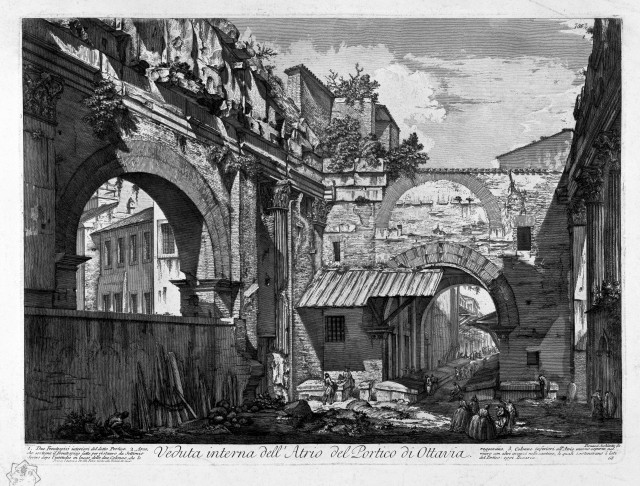

Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778), accomplished for the glories of Rome what Canaletto had begun a generation earlier for Venice, though with a difference. The apex of Venetian hegemony over the eastern Mediterranean had only recently passed, and perhaps that passing was not even fully apparent to Venetians of Canaletto’s generation. In Canaletto’s Venetian panoramas the contrast is between public splendor and private humility. In Piranesi’s work the architectural wonders of Imperial Rome are artifacts of an Arcadian past, almost invisible to medieval Romans, and now an occasion for archeology and nostalgia.

Piranesi studied as an architect and draughtsman in Venice, where his uncanny mastery of linear perspective became apparent. He moved to Rome in 1740 and studied etching and engraving, and at the same time furthered his architectural studies by measuring meticulously the ancient ruins that underlay the 18th century city. These experiences combined to inform his lifelong magnum opus, a series of etched drawings of vedute, or views, of Rome, in which the ruins of its ancient monuments survive cheek by jowl with the litter of their successors through the centuries. In many cases, Piranesi’s views are examples of visual archeology, because he used his architectural knowledge and measurement data to “restore” ancient buildings in his drawings as they would come to be restored literally by future generations. In addition, Piranesi’s mastery of perspective allowed him to alter the scales of monuments, convincingly, to accentuate a sense of romantic nostalgia for a lost classical past. Piranesi was enormously successful in publishing and selling his etchings during his lifetime, and a huge industry persists to this day in the trade of his original prints, posthumous prints of his original plates, restrikes made from those plates, and lithographic posters printed from photographs of his original work.

Reproduced here is Piranesi’s View of the Inside of the Atrium of the Porta di Ottavia, in which contemporary Romans seem to toil almost oblivious of their noble surroundings.

Hubert Robert (1733-1808) and Giovanni Paolo Panini (1692-1765) are the two additional view painters whom Nick invokes to suggest the insignificance, in comparison to its architectural surroundings, of the figure lurking in his doorway (soon to be identified as the all too significant Uncle Giles). Robert was a Parisian, Panini from Piacenza in northern Italy, and both found their way to Rome as a result of renewed Europe-wide interest in the excavation of classical ruins. Panini was the elder artist and employed Robert in his workshop; both associated with Piranesi and with Robert’s French contemporary, Jean-Honore Fragonard. While neither Robert nor Panini are very popular with contemporary general audiences, their reputations among scholars has not diminished noticeably, and both painters were enormously successful in their time, especially among wealthy tourists on the Grand Tour who could afford to take home a really grand souvenir of Rome.

Both Robert and Panini were fond of architectural fantasies and dreams of a classical past, as in Robert’s Temple of Philosophy at Ermenonville, but both were also masters of documentary exactitude, as the Panini Interior View of St. Peter’s, Rome, suggests exquisitely.

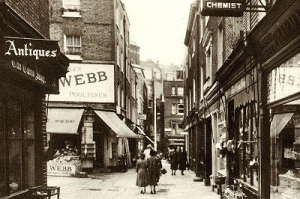

- photo of Shepherd’s Market, 1938

http://www.shepherdmarket.co.uk/history.htm

We will finish with a photo of Shepherd’s Market, taken a few years later in 1938, to show how much morning light, mood, and imagingation romanticized Jenkins’ perception.

Mr. Deacon’s Shop

When Nick first visted Mr. Deacon’s shop, it was closed. “Through the plate glass, obscured in watery depths, dark green like the interior of an aquarium’s compartments, a Victorian work table, papier mache trays, Staffordshire figures, and a varnished scrap screen — upon the sombrely coloured montage of which could faintly be discerned shiny versions of Bubbles and For He Had Spoken Lightly of a Woman’s Name … [BM 172/163 ]”

Bubbles, a picture of innocent childhood, is by John Everett Millais, whom we have already introduced as the painter of The Boyhood of Raleigh. Millais sold reproduction rights to Bubbles to the A.F. Pears Soap Company, which made it into a massively distributed advertising image, adding a bar of soap to the picture. When Tate Britain presented a Millais exhibit in 2007, the headline of a review in The Guardian summarized the effect on Millais’ status: “Tate sets out to rescue reputation of artist tarnished by Bubbles.” (The Guardian review, for those interested, also revisits Millais’ scandalous romantic life.) When Lever Brothers acquired A.F. Pears Company, it also acquired the original oil, which it now displays in the Lady Lever Gallery. We will bet that the image in Mr. Deacon’s window showed the bar of soap.

John Arthur Lomax (1857 – 1923) is a British artist, who is nearly forgotten today. He does not even have a Wikipedia entry (accessed 11/16/13), the ultimate sign of disrespect in the Internet Age. For He Had Spoken Lightly of a Woman’s Name is more an illustration for a boys’ adventure story than a remembered work of art. Jenkins shows that Mr. Deacon’s store was a repository of popular culture rather than of high art, but tastes change, and today similar items, perhaps more polished than Mr. Deacon’s examples, are sold for hundreds of dollars, as illustrated by the three images at the beginning of the post.

One of our readers has provided a photo of a colored reproduction of the Lomax work.

- For He Had Spoken Lightly of a Woman’s Name

John Arrthur Lomax, 1905

photo courtesy of Marty Mulder Tetloff, Metro Tacoma Fencing Club - Luxuria

-

Nick’s momentous first visit to Stourwater, the redoubt of Sir Magnus Donners, is occasioned by his inclusion in a luncheon party there in the company of the Walpole-Wilsons. “The dining room was hung with sixteenth century tapestries. I supposed that they might be Gobelins from their general appearance, blue and crimson tints set against lemon yellow. They illustrated the Seven Deadly Sins. I found myself seated opposite Luxuria, a failing principally portrayed in terms of a winged and horned female figure, crowned with roses, holding between finger thumb one of her plump, naked breasts, while she gazed into a looking-glass, supported on one side by Cupid and on the other by a goat of unreliable aspect. The four-footed beast of the Apocalypse with his seven dragon-heads dragged her triumphal car, which was of great splendour. Hercules, bearing his clubs, stood by, somewhat gloomily watching this procession, his mind filled, no doubt, with disquieting recollections. In the background, the open doors of a pillared house revealed a four-poster bed, with hangings rising to an apex, under the canopy of which a coupe lay clenched in a priapic grapple. Among trees, to the right of the composition, further couples and groups, three or four of them at least, were similarly occupied in smaller houses and Oriental tents; or, in one case, simply on the ground.” [BM 199/190]

This richly symbolic art work is an invention of Powell’s, but one clearly based on actual models, if imperfectly so. Gobelin tapestries did not come into production until the seventeenth century, but Belgian tapestries were in full production in the sixteenth, when Nick supposes the Stourwater set originated. We believe that Cardinal Wolsey commissioned a set of Belgian tapestries depicting the Seven Deadly Sins for his residence at Hampton Court, but we have been unable to find an image of any of these, if indeed any survive. Because Wolsey’s palace became a possession of the Crown at his death, and has remained so since, it is possible that Powell viewed Wolsey’s tapestries as a visitor to Hampton Court Palace.

A tantalizing alternative is suggested by Cassidy Carpenter, a high-school-aged scholar at Andover in 2008, whose teacher posted his students’ essays on Dance in an online compendium. Carpenter argues that Powell’s Luxuria is modeled on The Triumph of Lust, a Belgian tapestry completed in 1533, based on a design by the Flemish painter Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1502-1550), himself the son of a tapestry weaver. Van Aelst’s tapestry does not match Nick’s description of Luxuria, but Carpenter makes a credible claim for its role as Powell’s inspiration.

Van Aelst was the mentor and father-in-law of Pieter Breugel the Elder. More information about the family is available on the DeMeijer family website, which reports that the Luxuria displayed in Madrid is “one of four surviving tapestries from a set purchased by Mary of Hungary in 1544.” The photos available of the tapestry provide little detail because of its size, but Carpenter has guided us to a more detailed reproduction in a Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition catalogue (Campbell Tapestry in the Renaissance: Art and Magnificence Yale University Press 2002, p 412-3); she points out that the tapestry which Powell describes is much more risque that the Van Aelst version of Lust. We show only thumbnails below because the book is copyrighted; follow the link to the book to see more detail.

Incidentally, the Seven Deadly Sins in question are not a universally constant set, but since medieval times are typically identified as gluttony, sloth, greed, envy, wrath, pride, and lust. Luxuria is the Latin formulation for that last and most fascinating trait. All the others do star turns in Dance, but Luxuria certainly gets top billing.Holbein’s Portrait of Erasmus

Erasmus

Hans Holbein the Younger, 1523

The National Gallery On loan from the Longford Castle collection,

photo public domain from Wikipedia CommonsHolbein’s Portrait of Erasmus [BM 193,196/183,186]) hangs at the far end of the Long Gallery at Stourwater. Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1547) was born in Augsburg, in what is now Germany. Holbein arrived in London in 1523 with a recommendation to Thomas More from Erasmus. Holbein’s portraits of Henry VIII, More, and other court figure like Anne Boleyn established his preeminence in British portraiture. He painted at least 3 portraits of the humanist scholar Erasmus of Rotterdam and probably brought 2 of these to England; he gave the portrait currently hanging in the National Gallery as gift to the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Powell’s conceit, that a national treasure such as the Holbein Erasmus could be displayed in the private castle of a rich magnate, is culturally accurate. The Fifth Earl of Radnor, who owned Longford Castle, sold Holbein’s The Ambassadors to the National Gallery in 1890. Litigation ensued about the right of the Earl to sell this painting, possibly to the detriment of his heirs. The court in allowing the sale, noted that twelve other Holbeins, including Erasmus, remained at Longford Castle, which has now lent Erasmus to the National Gallery.

Powell was married to Lady Violet Pakenham, of the celebrated Anglo-Irish Longford-Fraser writing dynasty. We do not know whether this Irish Longford family is related to the Earls of Radnor who own Longford Castle in Britain, but we are sure that Powell’s aristocratic connections made him very familiar with great private art collections.

Gainsborough’s Mrs. Siddons

During the portentous luncheon at Stourwater, Nick is struck by Lady Huntercombe, “whose features and dress had been designed to recall Gainsborough’s Mrs. Siddons.”[BM 209/199]. Later, at Stringham’s wedding to Peggy Stepney, Nick notices Lady Huntercombe to be “arrayed more than ever like Mrs. Siddons.” [BM 236/226]

Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) was one of the brightest stars of English portraiture in the eighteenth century. Gainsborough was of modest birth but was identified as a talent early in life and sent to London to study under William Hogarth. He worked first in Ipswich, then Bath, and finally London, where he became a founding member of the RoyalAcademy and a favorite of George III, though Gainsborough’s chief rival, Sir Joshua Reynolds, won the king’s preference for court painter.

Like most other portraitists of genius, Gainsborough’s heart lay elsewhere—in this case with landscape painting––but wealthy sitters paid the bills. The wealthy sitter in question here was Sarah Siddons (1755-1831), a renowned actress of the day and a stunningly fashionable figure. Gainsborough’s dashing portrait of Mrs. Siddons from 1785 was a prized exhibit in the National Gallery, where it resides still, so Nick and his luncheon companions would readily recognize Lady Huntercombe’s emulation of it. Her choice to dress at the Stourwater luncheon in fashions that were popular in the mid eighteenth century says something of Lady Huntercombe’s notion of her own station. What Nick implies about the design of Lady Huntercombe’s “features” can only be guessed. Perhaps a clue is to be found in a remark Gainsborough is reputed to have made while working on Mrs. Siddons: “Confound the nose, there’s no end to it!”

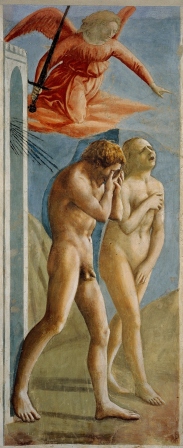

Masaccio to Matisse

On at least four occasions, different characters in Dance use alliterative contradictory pairings of artists’ names to emphasize ignorance of art. While this name dropping or name dissing may not be as important as other artistic references for understanding the text, we will join Powell’s fun by providing visual examples of the contradictions.

Touring Stourwater, Jenkins “felt certain that Sir Magnus was secure in the exact market price of every object” there. This reminded Jenkins of Barnby’s description of “a chartered accountant, scarcely aware of how pictures are produced, who could at the same time enter any gallery and pick out the most expensive work there ‘from Masaccio to Matisse’…” [BM 211/201]

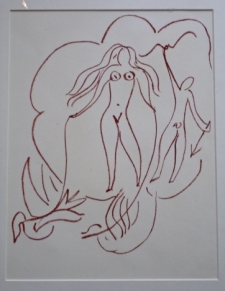

Masaccio (1401-1428) was the first great painter of the Quattrocento in Florence; Henri Matisse (1869-1954) helped lead the great changes in modern art in France in the first half of the twentieth century. To compare their styles on the same subject, we have taken some chronological liberty; the Matisse Adam and Eve was done about twenty years after the scene at Stourwater, but before Powell wrote BM. While the Masaccio is priceless and unavailable, today the chartered accountant could buy the Matisse lithograph (from an edition of 320) from Caroline Wiseman Modern and Contemporary for £1000 (accessed 12/1/13).

- Adam and Eve, Florilege des Amours de Ronsard

Henri Matisse, 1948

16 by 13 inches

Original lithograph in sanguine on Arches paper.

Inspired by the love poetry of Ronsard; Printed at L’Atelier Mourlot; Published by Alberta Skira in an edition of 320 - Ruben’s Chapeau en Paille

-

As Nick is leaving Stourwater, Jean Duport somewhat awkwardly invites Nick to “dinner, or something,” with her husband Bob Duport. Nick reflects on Jean’s manner: “she reminded me of some picture. Was it Rubens and Le Chapeau de Paille: his second wife or her sister? There was that same suggestion, though only for an instant, of shyness and submission.” [BM 226/216]

Le Chapeau de Paille is the title given to the 1625 portrait by Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) of Susanna Lunden, the older sister of Helena Fourment, Rubens’ second wife. Some historians have posited that the painting may in fact be a portrait of Helena herself, though if so, it would have been painted before they were married. In any case, Rubens has created the image of a beguiling beauty who peers out at the viewer from under the shade of her chapeau with a shy but unremitting gaze. This beloved portrait, now in the National Gallery in London, is by no means the kind of complex composition for which Rubens is esteemed, but it exemplifies his uncanny ability to whip up a Baroque fantasy of swirling costume, clouds and sky that nevertheless maintains its still center in his sitter’s enigmatic personality.

Le Chapeau de Paille

Peter Paul Rubens, ~1625

oil on oak, 31 by 21.5 inches

The National Gallery, London

photo from Wikimedia CommonsRubens is the pre-eminent artist of the Flemish Baroque, or indeed of the whole of European art of the period, since he accomplished a synthesis of the Northern tradition with that of the Italian Renaissance masters whom he studied closely. Based in Antwerp during his maturity, Rubens headed a school there, what we might call a factory, where he produced not only portraits but religious altar pieces. history paintings, scenes from classical mythology, and allegorical landscapes. His work was largely produced in the service of the royal houses of Europe, and his prodigious output now graces the museums and private collections of every European capital. In his “spare” time, Rubens served as private diplomat for Isabella, the sovereign of the Netherlands, in her elaborately complex dealings with Spain, England, and France.

Isabel Brandt

Peter Paul Rubens, 1621

drawing

The British Museum

photo editted and cropped with photoshop from Wikimedia CommonsNick allows that “Perhaps it was the painter’s first wife that Jean resembled, though slighter in build. After all, I recalled, they were aunt and nieces.” Here he is referring to Isabella Brandt, Rubens’ beloved first wife, who died in 1626. There are several portraits of Isabella Brandt, but no doubt Nick is thinking of this superb drawing in the British Museum. Here Isabella’s resemblance to her niece Susanna is apparent, but the younger woman’s shyness is replaced by Isabella’s confidence, strengthened by Rubens’ remarkable ability to virtually project the head out from the weave of the paper on which it is drawn.

Daguerreotypes on Mr. Deacon’s Mantle

Daguerreotypes of Deacon’s mother and of Walt Whitman in oval frames stood on Mr. Deacon’s mantlepiece. The features of his mother “so much resembled her son’s as for the picture, at first sight, almost to create the illusion that he had himself posed, as a jeu d’esprit in crinoline and pork pie hat. Juxtaposition of the portraits was intended, I suppose, to suggest that the American poet, morally and intellectually speaking represented the true source of Mr. Deacon’s otherwise ignored paternal origins. ” [BM 246/236 ]

Daguerreotypes, introduced in 1839, were the first widespread photographic method. The images were made directly on a silver plate; there was no photographic negative. Small daguerreotypes, about 2.75 by 3.25 inches, were widely available by the mid 1840s without great expense. However, the images were heavy and hard to view due to reflections from the silver, and by the early 1860s, daguerreotypes had been superceeded by other processes such as ambrotype and tintype, and sometimes images with these later techniques are mistakenly identified as daguerreotypes.

The pork pie hat also dates the photo. The pork pie hat was popular among women in the US and Britain from about the 1830s to mid 1860s; it was small and round with low flat crown and narrow turned up brim.

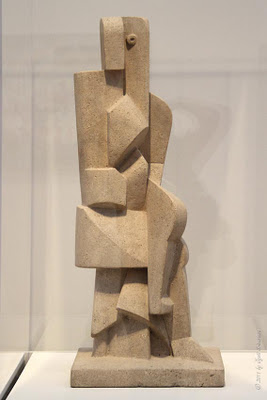

Mona

As he recalls Mr. Deacon’s birthday party, Nick remembers meeting Quiggin arriving uninvited, brought along by “a strapping black-haired model called Mona.” A bit later, Quiggin “looked across the room to where Mona was talking to Barnby and said: ‘It is a very unsual figure, isn’t it? Epstein would treat it too sentimentally, don’t you think? Something more angular is required, in the manner of Lipchitz or Zadkine.’” [BM 253-4/243]

Sir Jacob Epstein (1880-1959) was a British sculptor associated with Vorticism and various other shades of bold modernism. His work, nearly always figurative in subject, though quite varied in both medium and appearance, was often greeted with shock and outrage by the English public for its frank sexuality and modernist distortions. For Quiggin to suggest that Epstein’s take on Mona would be too sentimental is a joke that points in two directions: Quiggin in the 1920’s must have been quite a whopping avant-gardist to find Epstein sentimental, and Mona must have been quite severe of figure to leave Epstein not up to the task of representing her. These photos of Epstein’s carved figures for the London Underground headquarters suggest why we say so. The were unveiled in 1928, around the time that BM takes place, to great public furor.

Day and Night

Jacob Epsteim 1928 Portland Stone, carved for London Underground’s Headquarters at 55Broadway, London.

photos by Andrew Dunn

from Wikimedia Commons

Seated Figure

Jacques Lipchitz, 1917

Limestone

The Art Institute of Chicage

photo courtesy of Jyoti SrivastavaChaim Jacob Lipchitz (1891-1973) was born of Jewish parents in Lithuania, moved to France and became known as Jacques, and finally moved to the United States in 1940 to escape the German occupation. In the period just before A Buyer’s Market, Lipchitz had made his reputation as a Cubist figurative sculptor, working in the company and shadow of Picasso and Juan Gris. Later, Lipchitz softened his forms in favor of a more organic vocabulary, but this limestone figure of his from 1917 gives a sense of what Quiggin thinks might be necessary to capture Mona’s type.

Femme Debout

Ossip Zadkine, 1922

sculpture, Susse Foundry, Paris

photo from Wikipaintings .org

This artwork may be protected by copyright.Lipchitz’s contemporary, Ossip Zadkine (1890-1967) was an immigrant to France from Belorussia. Though Jewish as well, Zadkine managed to survive the war in France and lived there till his death. Zadkine’s sculpture and painting was a little less orthodox in its Cubism. But this example of a female figure from 1922, taken together with the Lipchitz, suggests that Quiggin has not underestimated a certain angular hardness that Mona will exhibit in the pages to come.

Artists models are one of many recurring topics in Dance. Mona is reputedly based on Sonia Brownell, who eventually married George Orwell. In TKBR (pp 161-162) Powell recounts his adventures publishing the autobiography of another model, Bette May, of whom Epstein did a bronze head. In a book review on artists’ models in SPA… (p251), Powell discusses the role of sexism and eroticism in our perceptions of models, and based on his own experiences sitting for portraits, says: “Certainly, few persons who have ever sat for a portrait can have felt anything but inferior while the process is going on…”

The Sea Giving Up the Dead That Were In It

Mark Members looked around the room at Mr. Deacon’s birthday party and said: “You must admit it looks rather like that picture in the Tate of the Sea giving up the Dead that were in it.” [BM 253/243]

And the Sea Gave Up the Dead Which Were in It

Frederic Lord Leighton, 1892

Oil on canvas, support 90 X 90 inches

Tate BritainLord Frederic Leighton (1830-1898) was one of the most famous Victorian painters, president of the royal academy, and the first British artist to have been ennobled. During much of his career, he was strongly influenced by Greek and Roman mythological themes. He was not particularly sympathetic to his contemporaries, the Impressionists, and modeled his later work on Michelangelo.

Leighton originally designed The Sea Gave Up the Dead as one of eight roundels intended for the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral; however, the proposed commission was rejected as “unsuitable for a Christian church.” Leighton painted this version for Sir Henry Tate about the time that Tate founded his museum of British art in the 1890’s.

The dramatic scene is based on a passage from the Book of Revelations. Members is brilliant, supercilious, and never quite lives up to his promise; here he uses the painting as a hyperbolic metaphor; by doing so, he says more about his personality than about the party.

Goya’s Maja Desnuda and Manet’s Olympia

Maya Desnuda

Francisco Goya, ~1795-1800

oil on canvas, 39×72 in.

Prado Museum

photo from Wikimedia.orgAfter Mr. Deacon’s funeral, Nick finds himself behind Mr. Deacon’s shop with Gypsy Jones and is more or less seduced into sleeping with her. In the aftermath of that most abstractly described liason, Nick is bewildered by Gypsy’s apparent indifference to him and absorption with herself. “. . . Gypsy lay upon the divan, her hands before her, looking, perhaps rather self-consciously, a little like Goya’s Maja nude––or possibly it would be nearer the mark to cite that picture’s derivative, Manet’s Olympia . . . .” [BM 269/258]

Francisco Goya (1746-1828) was the greatest Spanish painter and printmaker of his age, the more remarkable for his artistic journey from painter of romantic frivolities of aristocratic life, to court painter of portraits for Charles IV, to embittered satirist of social folly and the atrocities of war, and finally to fantasist of monstrous demons of the soul. His Maja Desnuda (Naked Mistress) is thought to be a product of his court-painter period, and its subject may be Goya’s own mistress, or an aristocratic woman of whom he was enamored, or a composite of several subjects. Regardless of the identity of its subject, the painting is startling for the frankness of her nudity and the confidence of her gaze at the viewer.