Barnby’s Murals Destroyed

We have been avoiding writing about Barnby’s frescoes for the Donners Brebner building because we know so little about them. They were commissioned by Sir Magnus Donners, completed about 1928, and received “a great deal of public attention.” [AW 31/24, CCR 14/9] Now that we are reminded that they were destroyed by a direct hit on building in the Blitz, we will provide some historical and geographical background that helps us better imagine Powell’s creations [SA 8/5. MP 118 /113].

Jenkins described the Donners Brebner building, on the south shore of the Thames across from Millbank, as “dominating the far shore like a vast penitentiary” [CCR 120/115] and “this huge shapeless edifice, recently built in a style as wholly without ostensible order as if it were some vast prehistoric cromlech.” [QU 218/225]

Millbank runs along the Thames south of Westminster to Vauxhall bridge; the Albert Embankment runs along the opposite side of the river. Both Millbank and the Albert Embankment sustained multiple bomb hits during the Blitz. After reading about Blitz damage in this part of London, we have reached a dead end in our search for Barnby’s frescoes. For example, the Tate Museum, now called the Tate Britain, was built in Millbank near the Vauxhall bridge late in the nineteenth century on the sight of an infamous penitentiary. The Tate sustained a direct hit, and damage to the building is still visible, yet no art was damaged.

Another approach is through Lord Beaverbrook, who shared some characteristics with Magnus Donners. Lord Beaverbrook was an art collector and did commision murals from contemporary British painters. The building that he built in Fleet Street in 1933 for one of his newpapers, The Daily Express, survived the Blitz and is today regarded by some as an Art Deco masterpiece, but we can see how others might view it as “without ostensible order.”

The former Daily Express Building, London

photo by Russ London from Wikimedia.org by Creative Commons license

The lobby of the building was designed by Richard Atkinson with bas relief sculptures by Eric Aumonier. Frescoes, by Barnby or others, are absent.

We have no idea if our speculations and digressions have anything to do with Barnby’s frescoes. We welcome insights from our readers.

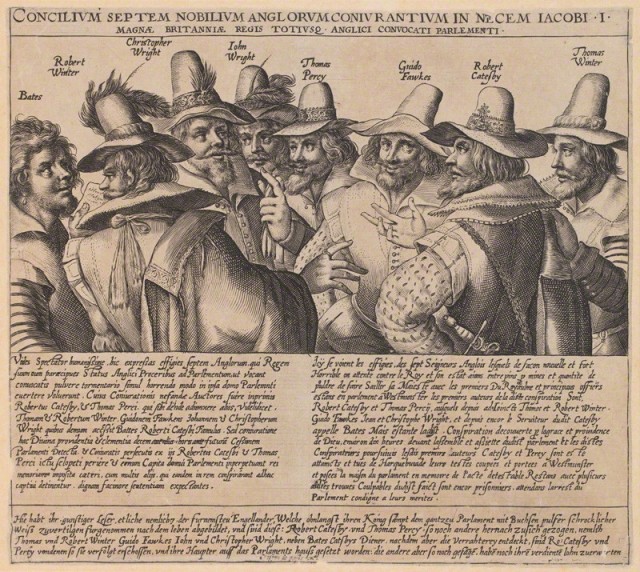

An Engraved Illustration of the Gunpowder Plot

Jenkins describes eating with General Liddament and his staff: “A single lamp threw a circle of dim light round the dining table of the farm parlour where we ate, leaving the rest of the room in heavy shadow, dramatising by its glow the central figures of the company present. Were they a group of conspirators — something like the Gunpowder Plot — depicted in the cross-hatchings of an old engraved illustration?” [SA 36-7/34 ]

The Gunpowder Plot

Crispijn de Passe the Elder, circa 1605

engraving, 7 7/8 in. x 8 1/8 in

from the National Portrait Gallery with permission by Creative Commons license

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 was an attempt by Guy Fawkes and others to blow up the Houses of Parliament. The failure of the plot is still celebrated in Britain by bonfires and fireworks as Guy Fawkes Night every November 5. The engraving above includes the only known contemporary portrait of Fawkes. His name appears above the third figure from the right; “Guy” becomes “Guido” in Latin. The artist is Crispijn de Passe the Elder (~1565-1637), a Dutch engraver who worked through a London publisher and bookseller to sell his prints in Britain. Powell might well have been familiar with this engraving because from 1962 to 1976 he was a trustee of the National Portrait Gallery, which has a number of portraits of him.

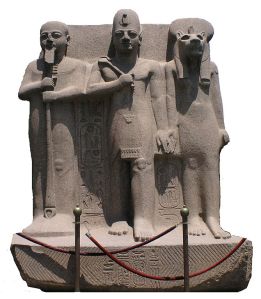

Egyptian Deities at General Liddament’s Mess

Nick attends the mess of General Liddament, a severe presence who is flanked at table by two colonels: “Here was Pharaoh, carved in the niche of a shrine between two tutelary deities who shielded him from human approach. All was manifest. Colonel Hogbourne-Johnson and Colonel Pedlar were animal-headed gods of Ancient Egypt. Colonel Hogbourne-Johnson was, of course, Horus, one of those sculptured representations in which the Lord of the Morning Sun resembles an owl rather than a falcon; a bad-tempered owl at that. Colonel Pedlar’s dogs’s muzzle, on the other hand, was a milder than normal version of the Jackal-faced Anubis, whose dominion over Tombs and the Dead did indeed fall within A&Q’s province.” [SA 37/35]

As he did in A Question of Upbringing (see QU 214/221, Le Bas’ Appearance), Powell here evokes impressions of Ancient Egyptian imagery more than references to particular works. Below is a sculpture of the Pharaoh Ramses II “shielded from human approach” by the gods Ptah (left) and Sekhmet (right).

Reliefs of Ramses II, Ptah and Sekhmet The Egyptian Museum, Cairo photo by Daniel Mayer, cropped by AnnekeBart from Wikimedia Commons by GNU Free Documentation License

Colonel Hogbourne-Johnson as the god Horus was easy to envision, though not as an owl, as Nick has it, but as a falcon, bad-tempered to be sure. Here is Horus as he is depicted at the Temple at Edfu from the first couple of centuries B.C.

The identities of Egyptian deities is not constant over the long evolution of the Egyptian pantheon, but Horus is generally known as the son of Isis and the rival of Set, slayer of Osiris, Horus’ father, or sometimes brother. Horus is also identified with the sun and the moon, and Pharaoh himself came to be identified with Horus while alive, then as Osiris after death. The Horus at Edfu, judging from his fierce expression, might easily be a colonel who aspires to become a general as soon as possible.

Anubis

white marble, height 62″

1st-2nd century AD

From Anzio, Villa Pamphili

Vatican Museum, Rome

photo from Wikimedia Commons by Creative Commons GNU license

Anubis, shown above, was the jackal-headed god who was associated, as Nick suggests, with mummification of the dead and supervision of souls into the afterlife. Colonel Pedlar as a mild-faced Anubis came readily to mind when we saw this Anubis in the Vatican collection. It is from the Roman period late in Egypt’s history and is actually a blend of Anubis and the Greek god Hermes. We liked how this more doggy Anubis sports military braids and medals and looks as if he would be right at home at General Liddament’s mess.

Emotional Colors

Stringham tells Nick about the time Lord Bridgnorth’s butler served macaroni to His Royal Highness the Duke of Connaught but failed to provide a plate on which to eat it. “I shall never forget my ex-father-in-law’s face, richly tinted at the best of times — my late brother-in law, Harrison Wisebit, used to say Lord Bridgnorth’s complexion recalled Our Artist’s Impression of the Hudson in the fall. On that occasion it was more like the Dutch tulip fields in bloom.” [SA 77/ 76]

We are unsure of the identity of “Our Artist,” but perhaps this a reference to The Hudson River School, a group of nineteenth century American painters who presented a dramantic yet realistic vision of American landscape. Thomas Cole (1801-1848) was born in Britain but moved to America, where he founded the movement; Cole wrote: “There is one season when the American forest surpasses all in the world in gorgeousness — that is the autumnal; — then every hill and dale is riant in the luxury of colour — every hue is there, from the liveliest green to the deepest purple from the most golden yellow to the intensest crimson. ” [“Essay on American Scenery” The American Monthly Magazine 1 (January, 1839)] We show a work by Thomas Worthington Whittredge (1820-1910 ), a later member of the Hudson River School, to illustrate how varied those hues can be.

The Artist at His Easel

Thomas Worthington Whittredge ,~1891

oil on paper on panel, 12 x 9 in

Private collection

photo in public domain from The Anthenaeum

Tulip Fields in Holland

Claude Monet, 1886

oil on canvas, 26 x 32 in

Musee d’Orsay

photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons and the Yorck Project

Speaking of tulips fields, the colors of the bed that dominates the lower left of Monet’s canvas shown here might be compared to a ruddy cheek, but our idea of Lord Bridgnorth’s complexion is actually clearer from reading Powell’s words than from seeing the candidate image. Of course, we do not know exactly where on the hot part of the spectrum Lord Bridgenorth glowered, but Powell rather economically uses the visual allusions to convey this emotional heat.

Thinking about color and emotion prompts us to compare Powell’s style to Proust’s much more extravagant treatment of the emotional power of color, his famous passage on the “little patch of yellow wall” that appears in Vermeer’s View of Delft. One of characters from In Search of Lost Time, the writer Bergotte, goes to the Jeu de Paume to see this painting. Gazing at the painting, “His dizziness increased; he fixed his gaze, like a child upon a yellow butterfly that it wants to catch, on the precious patch of wall. ‘That’s how I ought to have written,’ he said. ‘My last books are too dry, I ought to have gone over them with a few layers of colour, made my language precious in itself, like this little patch of yellow wall.'” (Proust, The Captive (La Prisonnière), volume 5 of À la recherche du temps perdu, C.K, Scott Moncrieff translator.)

View of Delft

Johannes Vermeer, 1660-1

oil on canvas, 38 x 46 in

Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague

photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commonson

Overcome by the beautiful color, Bergotte slumps dead in front of the painting. Critics debate exactly which dab of yellow in this painting killed Bergotte and how this passage reflects Proust’s own emotional response to the painting. In The Military Philosophers, Jenkins reflects on Proust, which will give us a chance to return to the Powell-Proust nexus.

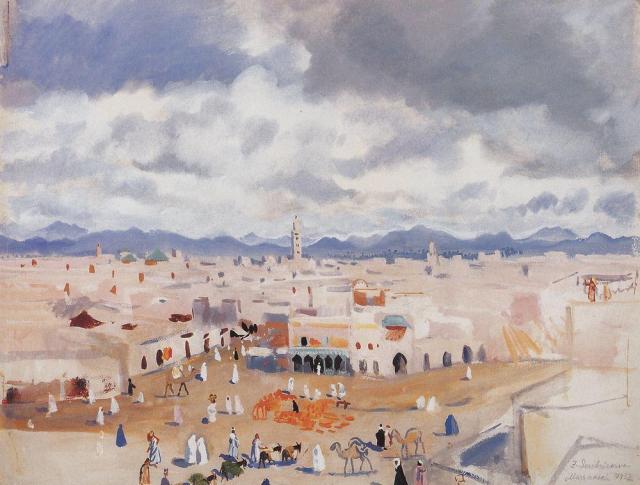

Rainy Day at Marrakesh

In At Lady Molly’s Nick was introduced by Chips Lovell to the the bohemian home of Molly and Ted Jeavons. There, amid priceless art works by Wilson and Greuze hung pastels by an unknown artist of Moroccan subjects. Now, during the chaos of the blitz, Nick has returned to the nearly-ruined Jeavons home, where Lady Molly has perished and all that remains of the art works are those Moroccan pastels. “The pastels, by some unknown hand, of Moroccan types remained. They were hanging at all angles, the glass splintered of one bearing the caption Rainy Day at Marrakesh.” [SA 164]

In our QA post Wilson and Greuze at the Jeavons’s we offered a pastel of a domestic scene in Marrakesh by Zinaida Serebriakova, from 1928, as a likely example of what the Jeavons’s might have collected. Continued searching strengthens our hunch that Serebriakova’s work might indeed have turned up in the heterogeneous Jeavons collection. Zinaida Serebriakova (Russian, 1884-1967) is celebrated as one of the first female painters of the early Modernist period, though her most famous works retain a classical rather than revolutionary nature. Serebriakova made many pictures of her travels in Morocco, though none, alas, are captioned Rainy Day at Marrakesh. Indeed, Marrakesh’s scant annual rainfall insures that few rainy views are likely to turn up in any artist’s oeuvre, but a watercolor of Marrakesh by Serebriakova suggests at least a touch of rain might be predicted, judging from that sky.

Morocco. Marrakesh

Zinaida Serebriakova, 1932

from WikiArt.org by fair use principles, copyright status unknown

The storage of the Wilson and Greuze in a safe location before the bombing is an example of a more general preservation of art in British collections by removal early in the War from London to protected sites in the country side.