The Acceptance World (AW) is nominally about the commercial milieu where many of Jenkins’ friends and contemporaries work. This volume is set in 1933, the heart of the Great Depression, yet Jenkins’ tale is much more about society, art, and the murmurs of his own heart, than about economics.

Doors of the Temple of Janus

The Ufford hotel had a large double drawing room, divided by a pair of doors, apparently permanently closed, into a lounge and a writing room. Jenkins surmises: “Perhaps, like the doors of the Temple of Janus, they are closed only in time of Peace; because years later, when I the saw the Ufford in war-time these particular doors had been thrown wide open.” [AW 9/3]

Roman coin from Nero’s reign showing the Doors of the Temple of Janus

picture from Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com via Wikimedia Commons

The story of these doors, closed in only in time of peace, is recorded in Plutarch’s Lives. (Life of Numa, XIX-XX, translation of the Greek edition ~1517) In Rome, the doors were rarely closed, because some part of the Empire was almost always at war. Jenkins, looking back from the 1950s, is reminding us how much life in Britain in the 1930s was about to change. Janus was shown as having two faces because as a king he turned men from barbary to civilization; January was named for him in honor of good government. The original temple, adjacent to the Roman Forum, no longer exists, and the best images are from old coins.

Bolton Abbey in the Olden Times

Jenkins meets his Uncle Giles in the lounge of the Ufford Hotel. Among the bleak, faded decor, he notes “an engraving, placed over the fireplace, of Landseer’s Bolton Abbey in the Olden Times.” [AW 10/4]

Sir Edwin Henry Landseer, RA (1802-1973) was famous for his animal paintings and sculptures. He taught Queen Victoria and Prince Albert etching and was a favorite of the artistocracy and of the Royal Academy. Much of his income, however, came from sale of his engravings to the middle class. He was the son of an engraver and many of this paintings were distributed widely as engravings by his brother Thomas.

Bolton Abbey is one of Landseer’s most popular paintings and has been engraved at least three times. We display this sample (available as of January 18, 2013, at www.oldrareprints.com) because its damaged frame and browning center make it possible to imagine that this very piece is the one that once decorated the Ufford. Landseer’s talent for depicting animals is evident here in the dogs and game, which Jenkins describe as “a crowded scene of medieval plenty…”

St. John Clarke and the Kensington Garden Sculptures

Jenkins discusses St. John Clarke’s interest in art and his suitability to write an introduction to The Art of Horace Isbister: “That a well-known novelist should take on something that seemed to call in at least a small degree for an accredited expert on painting was not so surprising as might at first sight have appeared, because St. John Clarke, although quieter of late years, had in past often figured in public controversy regarding the arts. He had been active, for example, in the years before the war in supporting the erection of the Peter Pan statue in Kensington Garden; a dozen years later vigorously opposing the establishment of Rima in the bird sanctuary in the same neighborhood” [AW 26/19] Jenkins continues, reflecting on Clarke’s views on the Haig Statue and on Post Impressionism.

In 1902, J. M. Barrie published his first Peter Pan book, The Little White Bird, and commissioned Sir George Frampton to build a statue of Peter for the Kensington Gardens. In 1904 Barrie wrote his famous play about Peter and in 1906 adapted the Kensington garden portions of The Little White Bird for the book Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens. Sir George Frampton, R.A. (1860-1928) was part of the late nineteenth century British New Sculpture movement, which concentrated on natural, life-like figures. Seven other castings of this beloved statue are displayed around the world.

Rima, sculpted by Sir Jacob Epstein for the Kensington Garden bird sanctuary in 1925 is a distant departure from New Sculpture. Rima, another popular figure of children’s literature, was a girl who lived the jungles of Venezuela in Green Mansions: A Romance of the Tropical Forest by W.H.M. Hudson (1904). St. John Clarke’s contrasting views of these two statues reflected public controversies in London in the late 1920s. Epstein’s work was greeted by some as a grotesque atrocity, but others welcomed it. The critic Holbrook Jackson wrote: “The statue of Peter Pan is only tolerable for the sentimental effect it has on children who have been wrongly brought up. Rima is one of the greatest examples of the sculpture of modern times.” In 1927, Rima was defaced with green paint; whether this was simple vandalism or an act of public criticism is unknown, but in August, 1928, Peter Pan was tarred and feathered, bringing tears to the eyes of many of its admirers; some believed that Epstein’s supporters were retaliating for the green paint. In 1929, Rima got the tar and feathers. A week later a tar attack on another Epstein piece was foiled, and other attacks on Rima continued for years. Epstein quipped: “Michael Angelo’s David was stoned by the populace of Florence…so I feel I am in good company.” We are still in Kensington Gardens but, in artistic terms, have come a long way from the Victorian monuments; in a few lines Powell both illustrates Clarke’s aesthetic politics and calls our attention to cultural history.

St. John Clarke’s Artist Conversion

Barnby and Jenkins are discussing the prospect of St. John Clarke writing an introduction to the book on Isbister’s paintings. We have already learned some of Clarke’s artistic tastes from his comments on the Keningston Garden statues. In the dialogue, Powell touches on many aspects of the evolution of Modernism.

Jenkins: “St. John Clarke does not know a Van Dyck from a Von Dongen” [AW 31/25]

Almost the only thing these two Dutch painters share is the first four letters of their names and perhaps a penchant for unusual hats. Jenkins has already mentioned Van Dyck, the seventeenth century British court painter, in AQ. Van Dyck painted portraits of Lady Shirley and her husband in Rome.

Lady Shirley

Anthony Van Dyck, 1622

oil on canvas

H.M. Treasury and The National Trust, Petworth House (Sussex)

photo from the Yorck project via Wikimedia Commons

Powell, reviewing a book about Van Dyck, says: “One is struck by the manner in which van Dyck has treated the Shirleys as if they might be more exotic ramifications of the East India Company in 1840.” [SPA… p. 180]

Van Dongen (1877-1968) was a fauvist, who later identified with the German expressionists. We know nothing about the model for this portrait, but early in his career, Van Dongen did frequent the Rotterdam red light district and often painted its denizens. By the late 1920s, he was honored with the French Legion of Honor and the Order of the Crown of Belgium.

Woman with a Large Hat

Woman with a Large Hat

Kees Van Dongen, 1906

photo public domain in US from Wikipedia

Copyright presumed to be estate of Kees van Dongen.

“Ah, but he does now,” said Barnby. “That’s where you are wrong. You are out of date. St. John Clarke has undergone a conversion.”

“To what?”

“Modernism”

“Steel chairs?”

Wassily Chairs, Model B3

Marcel Breuer, 1925-6

Creative Commons license from Wikimedia Commons, contributed by Tankwart from Flickr

While working at the Bauhaus, Marcel Breuer (1902-1981) designed this chair made of extruded chrome-plated steel, just like a bicycle frame, and upholstered with canvas. Breuer named it after the painter Vassily Kandinsky, his friend who was also with the Bauhaus at that time. Copies remain commercially available.

“No doubt they will come.”

“Pictures made of shells and newspaper?”

Still Life with Chair Caning

Pablo Picasso, 1912

collage on canvas

Musee Picasson, Paris

copyright Succession Picasso,

In May, 1912, Picasso introduced the low-art tradition of decorative collage to modern high-art practice (Edwards and Wood, Art of the Avante Garde, Yale University Press) with his Still Life with Chair Caning. Braque soon responded with his own collages, both artists gluing found materials onto their canvases. The use of actual newsprint and bits of shells was to follow, but Picasso anticipates this in Chair Caning with the JOU, hinting at “journal,” French for newspaper, and the three connected arcs in the lower right, suggesting a scallop shell.

“At present he is at a slightly earlier stage…The outward and visible sign of St. John Clarke’s conversion … is that he has indeed become a collector of modern pictures — though as I understand it, he still loves them on this side of Surrealism. As a matter of fact he bought a picture of mine last week.” Barnby goes to to say that he expects to be commissioned to paint Clarke’s portrait.

Augustus John

by Adrian Maurice Daintrey

oil on canvas 31 by 26 inches

Manchester Art Gallery

from BBC Your Paintings

(c) Mr Vernon C. Wallis (great-nephew); Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

Barnby is thought to be based in part on Powell’s good friend Adrian Daintrey (1901-1988), to whom AW is dedicated. In Daintrey’s portrait of the artist Augustus John, we see bold brush strokes and splashes of color to contrast with the brown suit, which probably owe something to his heroes Matisse and Derain, a modern portrait style that might accommodate the limits of Clarke’s ‘conversion.’

Considering whether Clarke’s conversion would improve his life, Jenkins says: “But if you are not really interested in pictures, liking a Bonard doesn’t make you any happier than liking a Bouguereau.” [AW 33/27]

Nude After the Bath

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, 1875

photo public domain from Wikipedia.org

William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1095) was a French academic painter who often placed his realistic but idealized nudes in mythical or classical settings. He was very successful in the mid nineteenth century but was devalued by the Impressionists and their followers. “Degas and his friends used the term ”bouguerated” (bouguereauté) to derogate a finicky, overly finished painting surface.” (Grace Glueck, The New York Times 1/6/1985) Bouguereau was quite out of favor among modernists in the days of AW, but like his contemporary Alma-Tadema, had new admirers later in the twentieth century.

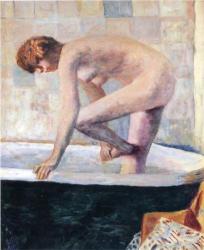

Nude Washing Feet in Bathtub

Pierre Bonnard, 1924

oil on canvas, 42 x 38 in.

Private Collection,

copyright status unknown

image from Wikipaintings. org

Bouguereau‘s countryman Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947) practiced a very different form of realism, sometimes called Intimism. He often worked from photos of his wife Marthe, using small brush strokes and colors mixed optically on the canvas to capture skin tones. Bonnard was a friend of Toulouse-Lautrec and was influenced by Gaugin and japonisme. He was riding the modern wave in the days of AW, with a major exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1933.

Isbister , “The British Frans Hals.”

When Isbister died, one of the death notices called him “the British Frans Hals.” [AW 36/30]

The Laughing Cavalier

Frans Hals, 1624

oil on canvas, 33 X 27 in.

Wallace Collection, London

photo public domain from Wikimedia Commns

We will start with an art history quiz: Which is true of Hals (Dutch ~1582-1666)? A. He, along with Rembrandt and Vermeer, is one of the enduring stars of the Dutch Baroque. B. He drank heavily and abused his first wife. C. He was a master of genre painting. D. He was in great demand as a portraitist by the Dutch bourgeoise. E. His portraits were vibrant with visible brushwork that was meticulously executed to appear spontaneous. F. He was broke and out of fashion before he died. G. His reputation revived in the nineteenth century, when innovators like Manet learned from Hals’ style. Answer: all of the above except for B. The story of wife abuse appeared in early biographies, but examination of the records showed that the abuser was a different Frans Hals, who also lived in Haarlem at the time. The growth of Hals’ critical stature is shown by enthusiasm for The Laughing Cavalier, which has been immensely acclaimed since it was first shown in Britain in 1872. So, which of these aspects of Hals led the obituary writer to compare him to Isbister? There is no suggestion of debauchery nor of mistreatment of Morwenna, his wife and model. He was hardly a contemporary master; later Jenkins attends the Isbister Memorial Exhibition “partly from a certain weakness for bad pictures, particularly bad portraits. ” [AW 113/106] Rather, the reference seems to refer to Isbister’s ability to sell portraits to the burghers of Britain, in spite of what Jenkins calls “the crudeness of his accustomed application of paint to canvas,” in no way comparable to Hals’ virtuso brushwork.

The Nymph at the Ritz

Jenkins, waiting to meet Mark Members at the Palm Court at the Ritz Hotel, gazes on a South American family seated in front of the fountain. “Away on her pinnacle, the nymph seemed at once a member of this Latin family party … Now she had strayed from her hosts to enjoy delicious private thoughts in peace while she examined the grimacing face of the river-god carved in the short surface of wall by the grotto. Pensive, quite unaware of the young tritons violently attempting to waft her away from the fountain by sounding their conches at full blast … ” [AW 37/31]

The Ritz, which is the site of a number of key scenes in AW, opened in 1906. Despite his upper class background, Jenkins was not usually among the stylish, rich, aristocratic habitues of the Palm Court. The fountain, called La Source, is part of the Belle Epoque interior decorated by Waring and Gillow to evoke Parisian elegance, akin to the Paris Ritz. Powell’s description of the nymph exceeds any two-dimensional picture in capturing the ambience that drew other beautiful people to the room. Today anyone with access to the Internet can reserve a seat at high tea there, which costs about £ 40 per person.

Delacroix’s Femmes d’Alger dans leur appartement

At his weekend visit to Peter Templer’s, Nick once again meets Peter’s sister Jean, now Jean Duport. “Once she had reminded me of Rubens’s Chapeau de Paille. Now for some reason––though there was not much physical likeness between them––I thought of the woman smoking the hookah in Delacroix’s Femmes d’Alger dans leur appartement.” (AW 58)

Femmes d’Algers dans leur apartement

Eugene Delacroix, 1834

color on canvas, 71 X 90 in

Louvre Museum

photo public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Eugene Delacroix (1798-1863) was the pre-eminent French Romantic painter of the nineteenth century, highly regarded by critics in his own time and continuously celebrated into the present. The term Romanticism applied to Delacroix’s work, and indeed almost defined by it, refers to its rejection of neo-classical ideas of stability and clarity of composition and of individual forms in favor movement, complexity and spatial ambiguity.

Delacroix largely avoided classical motifs in favor of scenes depicting the exoticism of North Africa and the near east, and from this interest arose his Femmes d’Algers of 1834. His historical paintings feature not the battles of antiquity but moments in more recent European history and in romantic literature when the heroic masses could be depicted as struggling against the tyranny of their oppressors. Thus, his most well-known painting is Liberty Leading the People, an homage to the July Revolution of 1830 against the reign of Charles X.

Nick compares Jean to an awkward, virginal saint in an early Flemish drawing, to Ruben’s sly cousin or wife, and to a hookah-smoking Algerienne, whom he says does not actually resemble Jean. These do not add up to a picture of Jean but to a picture of a confounded Nick, who cannot seem to get a handle on his fascination for Jean. The implication is that his fascination is not with her appearance at all but with her sexual allure, an implication that becomes more explicit as he moves from the saint to the exotic woman with the hookah.

Snowy Sisley Landscape

Driving to the Templer home on a snowy night with Templer, Mona, and Jean, Nick writes of Mona, “ . . . she jumped out of her side of the car, and ran across the Sisley landscape to the front door, which someone had opened from within.”

Alfred Sisley (1839-1899) was a British painter whom most viewers would identify as a French Impressionist, as indeed he identified himself. A British citizen, Sisley was born in Paris and spent most of his life in France, painting first rather in the manner of Corot, but gradually coming under the spell of his contemporaries Manet, Renoir, Monet, and Pisarro. Sisley exhibited repeatedly with the Impressionist group and always committed himself to the goals of plein-air landscape painting and the optical color-mixing effects for which the Impresssions became known. Evocation of the light on a snowy countryside was a favorite theme of Sisley and his colleagues, and a painting like this one of 1874 might have provided inspiration for Nick’s phrase, “the Sisley landscape.”

Snow on the Road, Louveciennes (Chemin de la Machine)

Sisley, 1874

15 X 22 inches

private collection

photo public domain from Wikipedia

Reynolds, Boucher, Renoir

In a protracted exchange with Nick, Barnby insists on the truth-telling ability of painting over writing where women are concerned: “Writers always seem to defer to the wishes of the women themselves.” Nick replies, “So do painters. What about Reynolds or Boucher?” [AW 75/69]

Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792) was the pre-eminent British portrait painter of the eighteenth century, notable for his erudition and his ability to synthesize both Italianate and Northern painting traditions into his own elegant compositions. Reynolds was elected as the first president of the RoyalAcademy at its founding in 1768. Commentators on the National Gallery of London’s website relate that Reynolds’ portraits have not lasted well over the centuries, faulty pigments having caused the flesh tones to fade, for example. No doubt his women subjects would have appeared even more ravishing to their contemporaries than they do to us now, though in the case of Lady Jane Halliday, pictured below in Reynolds’ 1779 portrait of her, that would be hard to imagine.

Portrait of Lady Jane Halliday

Sir Josuya Reynolds, 1779

oil on canvas, 94 X 59 inches

National Trust, Waddesdon Manor (Buckshire, Great Britian)

photo public domain from the Yorck project via Wikimedia Commons

Francois Boucher (1703-1770), Reynolds’ younger French contemporary, is identified with the most extreme expression of decorative movement and delicate color known as rococo. Unlike Reynolds, who worked almost entirely in portraiture, Boucher energetically explored every genre of painting and made designs for decorative work in printmaking, porcelain and tapestry. Boucher, even at the height of his career and periodically since, has been criticized for elevating style over substance, but no objective observer could fail to acknowledge Boucher’s mastery in asserting a particular vision of feminine beauty, as exemplified by this image of Venus from 1751, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Toilet of Venus

François Boucher, 1751

oil on canvas, 43 X 34 in

Metropolitan Museum of Art

photo public domain from Wikimedia Commons

Later, Barnby insists, “In writing . . . there is no equivalent, say, of Renoir’s painting. Renoir did not think that all women’s flesh was literally a material like pink satin. He used that color and texture as a convention to express in a simple manner certain pictorial ideas of his own about women. In fact he did so in order to get on with the job in other aspects of his picture. I never find anything like that in a novel.” To which Nick responds, “You find plenty of women with flesh like that sitting in the Ritz.” [AW 75/69]

Nick had had this thought earlier, while actually at the Ritz: “Among a sea of countenances, stamped like the skin of Renoir’s women with that curiously pink, silky surface that seems to come from prolonged sitting in Ritz hotels, I noticed some familiar faces.” [AW 40/34]

Pierre Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) was the French figurative painter most closely associated with the strand of Impressionism that sought to unite the Impressionists’ focus on the mundane aspects of middle-class life with painting’s traditional mission of celebrating and idealizing the glories of feminine flesh. Barnby insists that Renoir might portray women’s physical presence in the same way whether they were to be seen in the bath, the dance hall, or in the lobby of the Ritz.

After the Bath

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1888

oil on canvas, 26 X 21 in

private collection

photo public domain from Wikimedia Commons via the Yorck Project

Indifferent Seascapes

Quiggins surveys the Templer’s cottage. “His eyes continued to stray over the very indifferent nineteenth- century seascapes that covered the walls; hung together in patches as if put up hurriedly… ” [AW 87/ 80]

The tradition of painting the sea must be nearly as old as painting itself. British painters in the the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were inspired particularly by Dutch seventeenth century marine painters. (see, for example, Seascapes: Marine Paintings and Watercolors from the U Collection shown at the Yale Center for British Art). Some of the finest artists of the nineteenth century counted seascapes among their works, so why concentrate here on the indifferent? Once again, Jenkins is reflecting, somewhat superciliously, on the tastes and patrimony of his friends; the seascapes had hung in Templer’s parents’ seaside house. What is more intriguing to us is how Powell introduces these paintings so casually here, with no hint that he will revisit them in more detail in the concluding pages of Dance; we will speculate more about them then. In the meantime, if you want to inexpensively hide the divots in your wallpaper, go to eBay and bid on nineteenth century seascapes. Today (March 1, 2014), the watercolor below had an asking bid of £21.

Coastal Scene

George Dunketon Hiscox (1840-1909)

watercolor

At the Isbister Memorial Exhibition

Jenkins attends the Isbister Memorial Exhibition “partly for business reasons, partly for a certain weakness for bad pictures, especially bad portraits.” [AW 113/106] He reflects:

“Pictures, apart from their aesthetic interest, can achieve the mysterious fascination of those enigmatic scrawls on walls, the expression of heaven knows what psychological urge on the part of the executant; for example, the ever anonymous drawing of Widmerpool in the cabinet at La Grenadière.” [AW 113/106]

Jenkins revisits portraits, like that of Lord Aberavon, and also mentions Isbister’s genre paintings, like Clergyman Eating An Apple and The Humorists. In 2007-8 the Royal Academy mounted an exhibition of scenes of the quotidian– From All Walks of Life: Genre Paintings from the Royal Academy Collection — but so far we have not found a reasonable facsimile for Isbister’s genre oeuvre. We welcome hearing from readers if they have a candidate to show here.

As he wanders through the exhibit, Jenkins meets an number of old friends. Sir Gavin Walpole-Wilson takes some delight that Isbister has painted his old rival Saltsonstall to look like “the Christmas Tree of Taste.” [AW 115/108 ]. Sir Gavin mocks Saltonstall’s pretension as The Man of Taste: ” with his vers de societé, and all his talk about Foujita and Pruna and goodness knows who else — but when it comes to his own portrait, it’s Isbister.’ [AW 116/109]

Léonard Tsuguharu Fujita (1886-1986 ) was a Japanese born painter and print maker who lived in Paris from 1913-1931, achieving some critical and financial success, but he no longer has the name recognition of many of his friends and contemporaries who led the burst of French artistic creativity of that period.

Pedro Pruna (1904-1977) also spent time in Paris and was considered a student of Picasso. His work included costumes and scenery of Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe. Later he returned to Spain and supported Franco.

Sillery is at the exhibit, musing about who should paint his portrait to hang in his College. [AW 119/112] Isbister is no longer available, and the College is too conservative to consider Barnby; in fact, Antonio Moro represents the standard that they want to emulate. Moro (Netherlands 1519-1575), also know as Anthonis Mor van Dashorst, spent some time in Britain for his portrait of Queen Mary (1554). The portrait we show of Cardinal Granvelle illustrates Moro’s stern formality, which was so appealing to the dons.

Cardinal Granvelle Antonio Moro, 1549 oil on canvas, 43 X 33 in Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna photo public domain from Wikimedia Commons

In front of Countess of Ardglass with Faithful Girl, Jenkins sees Lady Ardglass admiring her own portrait. “Isbister had painted her in an open shirt and riding breeches, standing besides the mare, her arms slipped through the reins: with much attention to the high polish of the brown boots.

‘Pity Jumbo could never raise the money for it,’ Bijou Ardglass was saying.” [AW 121/113]

John William Godward (1861-1922) has been mentioned as a model for Isbister as a portraitist. Godward was a protege of Alma Tadema. Like Isbister, he was a member of the Royal Academy whose reputation waned with the advent of Modernism. Unlike Isbister, the vast majority of Godward’s subjects were women in Greco-Roman settings. He did not seem to paint horsewomen in brown boots; undoubtedly, however, he could have captured Bijou Ardglass’ allure.

The Mirror, John William Godward, 1899 oil on canvas 32 X 15 inches, private collection, photo public domain from Wikimedia Commons via the Art Renewal Center Museum

Mark Members on St. John Clarke

We already know Barnby’s opinion of St. John Clark’s taste. Now Mark Members, dismissed as St. John Clarke’s secretary, tells Jenkins, ” I can say without boasting that I had done a great deal to … improve St. J’s attitude towards intellectual matters. Do you know, when I first came to him he thought Matisse was a plage .. [French for ‘beach’]” [AW 130/123]

We have already touched on Matisse when we considered Mr. Deacon’s view of Post Impressionism and when Jenkins saw a Derain. Barnby playfully contrasted him with Masaccio.

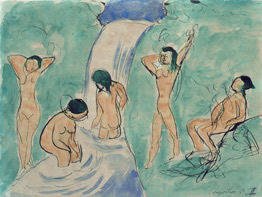

Matisse preceded Picasso at the forefront of French twentieth century art, gaining prominence in the first decade of the century as the driving force of Fauvism. Powell learned of Matisse’s paintings early in his years at Eton, about 1919 [TKBR 33]. Members is speaking in 1933; by then Matisse was so well known that he had been on the cover of Time Magazine (Oct. 20, 1930) after he had been the United States to sit on the jury of the 29th Carnegie International exhibition.

Bathers, Composition No. II,

Henri Matisse, 1909.

Watercolor on paper. The State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts,

Moscow

possible copyright

© 2010 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

There are many iconic Matisse images to choose; we picked this version of Bathers, both to recall Clarke’s plage and to reference Matisse’s homage to and evolution from Cézanne. A webpage of The Art Institute of Chicago illustrates how this work was pivotal in Matisse’s development .

Later in the conversation, Members says, “Then one morning at breakfast he says Cézanne was ‘bourgeois.'”[AW 133/126]

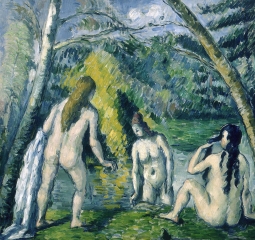

Cézanne (1839-1906) was certainly bourgeois in the Marxist sense; his father was a wealthy banker, and Cézanne gained financial independence from his inheritance. Nonetheless, he was an artistic revolutionary, who learned from the more radical of his immediate predecessors. His use of planes of color to create his compositions inspired succeeding developments like Fauvism and Cubism. Like Matisse, his work was shown in London in 1910 at Roger Fry’s Post Impressionist exhibit. Cézanne painted over 200 pictures of bathers. The work that we show belonged to Matisse, who acknowledge his artistic indebtedness to Cézanne. Matisse donated this canvas to the Petit Palais museum in 1936, making it the first Cézanne Bathers to be displayed in a western museum.

At Foppa’s Club, Nick surveys the scene: “The Walls were white and bare, the vermouth bottles above the little bar shining out in bright stripes of colour that seemed to form a kind of spectrum in red, white and green. These patriotic colors linked the aperitifs and liqueurs with the portrait of Victor Emmanuel II which hung over the mantelpiece. Surrounded by a wreath of laurel, the King of Sardinia and United Italy wore a wasp-waisted military frock-coat swagged with coils of yellow aiguillette. The bold treatment of his costume by the artist almost suggested a Bakst design for one of the early Russian ballets.” [AW 152/145]

Vittorio Emanuele II di Savoia

artist unknown

Museo nazionale del Risorgimento, Torino

photo public domain from Wikimedia Commns

Victor Emmanuel II (1820-1878) succeeded his father as King of Sardinia-Piemonte during the tumultuous mid-19th century period of warfare among the many Italian states and their several non-Italian proxies. Victor Emmanuel was effective in the unification movement known as the Risorgimento, and became the first king of the united Italy in 1870. Universally venerated in modern Italy as the father of his country, Victor Emmanuel’s painted and photographed likeness adorns wall wherever Italians gather . This painted portrait, of unknown authorship, omits the laurel wreath but vividly depicts the uniform he is almost always shown wearing.

Léon Bakst (1866-1924), born Lev Samoilovitch Rosenberg, was a Russian Jewish painter whose latter-day fame derives primarily from his career as a set and costume designer for the Ballets Russes under Serge Diaghilev. Bakst, in collaboration with Diaghilev and the choreographer Fokine, is credited with helping to bring ballet into the modern era, transforming it from a story-telling medium with mime and dance interludes into an integrated theatrical form. Music, movement, story, and visual design were unified into an expressive whole, in which Bakst’s designs served to add emotional intensity to the language of the body. Powell wrote of “the implications of irony, disillusionment, cruelty, that add force to Bakst’s Russian Ballet décor.” [TKBR 37] Bakst’s costumes were particularly admired for the lavishness of their color and ornamentation, and their exoticism. This 1910 costume design for Stravinsky’s Firebird has nothing of Victor Emmanuel’s military air to it, but one can see why the latter’s “wasp-waisted military frock-coat swagged with coils of yellow aiguillette” brings the Russian designer to Nick’s mind.

Carriage and Three Gentlemen on Horses

Constantin Guys, 1860

ink and wash with watercolor on paper photo public domain from Wikimedia Commons

The House of Card

Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin, 1737

oil on canvas, 24 x 28 in

National Gallery, London

photo public domain from Wikipaintings.org

Actually, Chardin’s reputation is built on his still-life paintings, which also were also informed by his understanding of 17th century Dutch paintings, but unlike those inspirations are now widely considered the first truly modern still-lifes. This is in part because they renounce all symbolism of their Dutch inspirations, and seem simply to revel in the beauty of quotidian stuff, and to interrogate the miracle of seeing. Anne is being contrary when she professes interest only in Chardin’s highlights, but looking at the reproduction below of his 1728 still-life with a dead ray, one has to admit she has a point.

Braque and Dufy

When Jenkins first met Lady Anne Stepney in the late 1920s, Botticelli seemed to be the limit of her knowledge of art. However, by 1933, Stringham, speaking of his ex-sister-in-law, says: “I heard by the way, that Anne had got a painter of her own by now, so perhaps even Braque and Dufy are things of the past. ” [ AW 208/199] However, Stringham did not know the latest: Anne had moved on from her affair with Barnby and was now married to Dicky Umfraville.

Boats in Martigues

Raoul Dufy, 1908

27 X 22 in.

Courtauld Institute of Art, London, UK

from Wikipainting.org

This artwork may be protected by copyright.

Anne came to Braque and Dufy a bit late. Both were renowned by the first decade of the twentieth century. Braque (1882-1963) exhibited with Fauvists in 1905 and beginning in 1909, worked closely with Picasso, developing Cubism; at times they painted side by side.

Dufy (1877-1953) was also influenced by the Fauvists and later by the Cubists on the way to developing his own richly colored style. Dufy and Braque were friends from their youth in Le Havre, and we have chosen these two examples from their extensive portfolios, because they were done around the time that they were painting together in l’Estaque, in the sixteenth arrondissement of Marseille, a time when their reputations were growing, long before Anne Stepney cared about them.

Pictures in Stringham’s Flat

When Jenkins and Widermerpool bring the drunk Stringham back to his flat, Jenkins is reminded of Stringham’s room at school [AW 214/205]. On the walls hang the racehorse prints of The Pharisee and Trimalchio, pictures of Stringham’s parents, a drawing by Modigliani, an engraving in the style of Hollar, and “a set of coloured prints of a steeplechase ridden by monkeys mounted on dogs.”

We have already discussed the racehorse prints. The Modigliani will reappear later in Dance in more detail; we will explore it then. The engraving is of Glimber, the large seventeenth-century home, which Stringham’s mother owned as a life estate from her first husband.

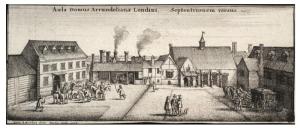

Arundel House fromthe N.

Wencelaus Hollar

engraving, 9 X 20 cm

The Wencelaus Hollar Digital Collection, The University of Toronto

Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-1677) was a Bohemian artist, etcher, engraver, and cartographer who came to England in 1636 in the retinue of Lord Arundel, whom he had met that April in the Rhineland. Arundel was one of the greatest art collectors of the seventeenth century and became Hollar’s patron; for a time Hollar was drawing master to the Prince of Wales, later Charles II. John Aubrey, whom Powell wrote about in John Aubrey and His Friends (1948), described Hollar as a “very friendly good-natured man as could be, but Shiftless to the World, and dyed not rich.” His etchings and engravings show a wide range of subjects in photographic detail; we agree with Powell, who regarded him as an “astonishingly accomplished” artist. [SPA… 182-184]

As for the comic steeplechase scene, we have actually found a Currier and Ives print that matches the description. Currier and Ives were prolific popularizers of art during the Victorian era, producing nearly 7500 lithographs from their New York presses between 1834 and 1907. They sold their work through diverse outlets, including a London office, where Stringham’s family might have bought the print shown below.

Steeplechase Cracks

Currier and Ives

Hand colored lithograph

14 X 9.75 inches

photo from website of the Springfield Museum

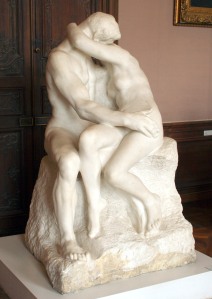

Rodin’s Le Baiser

AW concludes with Jenkins musing on love as he rushes to meet Jean; in his pocket is a French postcard from her, showing “a man and a woman sitting literally one on top of the other in an armchair upholstered with crimson plush.”

“The mere act of a woman sitting on a man’s knee, rather than a chair, certainly suggested the Templer milieu. A memorial to Templer himself, in marble or bronze, were public demand ever to arise for so unlikely a cenotaph, might suitably take the form of a couple so grouped. For some reason — perhaps a confused memory of Le Baiser — the style of Rodin came to mind. Templer’s own point of view seems to approximate to that earlier period of the plastic arts. Unrestrained emotion was the vogue then, treatment more in his line than some of the bleakly intellectual statuary of our own generation. ” [AW 222/213 ]

Le Baiser

Auguste Rodin, 1889

marble 72 x 44 x 46 in

Rodin Museum, Paris

photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons

Rodin first sculpted Le Baiser (The Kiss) in 1882 as a representation of Paolo and Francesca. The story, from Dante’s Divine Comedy, is that Francesca’s husband killed them when he surprised them in their first kiss. The French government commission an enlargement of the work in marble, which Rodin first displayed in 1898. He subsequently made other marble copies, and many bronzes casts have been made as well.

Auguste Rodin (1840 -1917) grew up in the Parisian working class and evolved his style through apprenticeship and travel in France, Belgium, and Italy, until he began to exhibit his own large figures in 1877. Powell described Rodin [SPA 247-249] as inherently conservative, dedicated to Michelangelo, but having a revolutionary impact on the art of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. He was a student of anatomy, in part from his friendship with the great neurologist Charcot. He was a compulsive womanizer, who viewed his depiction of women as homage to them, showing them as full partners with men in ardor. When it was first exhibited, some viewed Le Baiser as inappropriate for display to the general public. Perhaps it is this erotic effect of Le Baiser that Jenkins refers to when he says, “unrestrained emotion was the vogue then.”

Reviewing AW when it was published in 1955, Kingsley Amis wrote:

“Though so firmly located in the sequence which includes it, The Acceptance World differs from its predecessors in some elements of presentation. There is a departure from the earlier practice whereby all manner of paintings and sculptures got brought in to provide decoration’ and imagery, the fictitious ones so vividly that one could hardly credit not having come across Mr. Deacon’s Boyhood of Cyrus, in particular, in some municipal gallery, and the real ones with such insistence that one wondered at times whether Mr. Powell might not have been intending finally to pass under review the entire corpus of Western visual art. ”

Looking back at our posts, we think that Amis seems to have overlooked the continued reflections on the growth of Modernism that Powell includes in AW. Rodin, because of his central role at the turn of the century, is a fitting final reference to visual art in AW. Jenkins, complaining of the “bleakly intellectual statuary of our own generation” and including references to artists like Epstein, Zadkine, and Lipchitz, emphasizes the constant turmoil of artistic evolution.