After many years in South America, Jean Duport reappears in London at the centenary exhibition of Mr. Deacon’s paintings. As she enters the gallery, Henderson remarks of Jean, “She looks like one of those sad Goya duchesses.” Later, Jenkins reflects, “Henderson was right about Jean. The metamorphosis, begun when the late Colonel Flores had been his country’s military attaché in London at the end of the war, was complete. She was now altogether transformed into a foreign lady of distinction.” [HSH 233/252]

This is to be Nick’s last glimpse of Jean Duport, whose austere beauty and sexual fascination have long haunted him. We first spied Jean in Question of Upbringing, when her mystery combined the appeal of a virginal saint and mysterious temptress [QU /75]. In Buyers’ Market Jean’s looks were compared to those of Rubens’ first and second wives, at once shy and alluring and confident and voluptuous [BM 226/216]. Then, in Acceptance World, the Romanticism of Delacroix’s hookah-smoking harem woman was invoked to add a note of exoticism to Jean’s allure [AW /58]. Later in Acceptance World Nick returns to the theme of medieval austerity to describe Jean’s beauty: “Her forehead, high and white, gave a withdrawn look, like a lady in a mediaeval triptych or carving … ” [AW 141/]. Here we could not help but be reminded of the Rogier van der Weyden (Netherlandish 1399-1464) portrait of a lady in the National Gallery in Washington D.C.

Portrait of a Lady

Rogier van der Weyden, ~1460

oil on panel, 13 x 10 in

National Gallery of Art, Washington

photo in public domain from the Google Art Project via Wikimedia Commons

For the carved version of the medieval lady, we propose the Mary Magdalene shown below, which may have originally stood in the Church of the Dominicans in Augsburg, Germany. Jenkins returns to Jean as a medieval image when he learns that she slept with Jimmy Brent during his own affair with her. “I thought of that grave gothic beauty that I had once loved so much, …. I thought her men are gothic too, being carved on the niches and corbels of a mediaeval cathedral….” [KO 183] We envision Mary Magdalene, dancing on a corbel above gargoyles who caricature the three unhappy lovers — Stripling, Jenkins, and Brent.

Saint Mary Magdalene

Gregor Erhart, 1515-1520

lime tree wood, polychrome, 71 x 18 x 17 in

Louvre Museum

© Musée de Louvre, 2011, Thierry Ollivier

Devils drag a sinner off to hell. Corbel at Notre Dame cathedral,Noyon, France

photo from London Stone Carving

on Twitter

@londoncarving

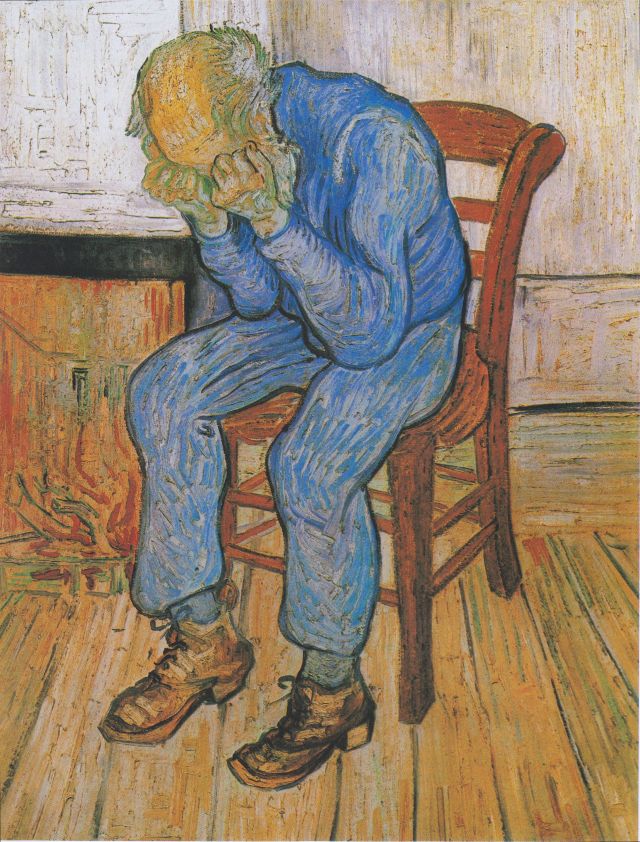

This is also our final recourse to Francisco Goya (Spanish 1746-1828), whose multi-faceted career we have considered twice earlier in Dance: in Buyers’s Market as a painter of a scandalous nude, and in Cassanova’s Chinese Restaurant as a Romantic chonicler of the life of the peasantry. There is also the Goya of the Spanish royal court, official painter of its noble family, the Goya who became a scathing political and social satirist, and finally a misanthrope of overwhelming visual rage. But long before the tragic final act of Goya’s career, he maintained a thriving practice as a portraitist to an aristocratic clientele that valued his special gifts in that genre. Those gifts included a delightful delicacy of touch and facility with likeness, but the flattery of his portraits consisted not so much in the prettifying of his subjects as in his ability to suggest a sympathy for their simple humanity, regardless of their wealth and station.

The Duchess of Alba

Francisco Goya, 1797

oil on canvas, 83 x 59 in

Hispanic Society of America

photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons

We show Goya’s 1797 portrait of the Duchess of Alba dressed in black, often called The Black Duchess, as an example of one of his “sad duchesses.” Powell’s allusion to Goya here is especially appropriate to Nick’s regard for Jean, as, historically, rumors have circulated that Goya’s regard for the duchess was romantic, even if research suggests an unrequited love, at most. Though still in the prime of her maturity, the duchess mourns the loss of her husband, just as Jean Duport has lost her Colonel Flores. Still, Goya’s duchess betrays less sadness than a kind of bewildered isolation, and an indignant refusal to accept her condition. As from the start, Nick’s fascination with Jean Duport lies not in any conventional beauty but in something else that she is for him, now described as “a foreign lady of distinction.”