Jenkins served for a time as a liason to the Polish Army in Exile. He describes Michalski, one of the Polish aides-de-camp of his acquaintance: “Of large size, sceptical about most matters, he belonged to the world of industrial design — statuettes for radiator caps and such decorative items–working latterly in Berlin, which had left some mark on him of its bitter individual humor. In fact Pennistone always said talking to Michalski made him feel he was sitting in the Romanisches Café. His father had been a successful portrait painter, and his grandfather before him, stretching back to a long line of itinerant artists wandering over Poland and Saxony.

‘Painting pictures that are now being destroyed as quickly as possible,’ Michalski said.” [MP 31/27]

At times Powell’s artistic references pertain to a specific work, perhaps previously unknown to many of his readers (for example, The Omnipresent); other times, he is referring to an artistic fantasy, rather than to a real painting (for example, The Boyhood of Widmerpool). Pennistone is modeled on Powell’s friend and commanding officer Alexander Dru; many of the military attachés who appear in MP are modeled closely on officers Powell knew (TKBR 282-283). Was there a real family of artists like the Michalskis or is Powell simply paying homage here to a long tradition of Polish portraiture?

Nicholas Copernicus

artist unknown, 1580

tempera and oil on wood, 20 x 16 in

Regional Museum, Torun, Poland

photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons, source http://www.frombork.art.pl/Ang10.htm

Treasures from Poland, an exhibition of Polish art organized by the Art Institute of Chicago, showed Polish portrait painting dating from the Renaissance (as shown above) to the present. We have found a multigenerational family of Polish painters to illustrate this theme.

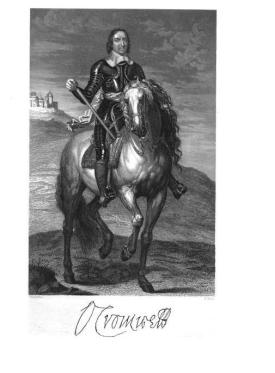

Juliusz Fortunat Kossak (1824 – 1899) specialized in historical and battle scenes; his portraits were of the military.

Prince Józef Poniatowski

Juliusz Kossak, 1897

oil on canvas

photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons

His son, Wojciech Kossak (1856 – 1942), also painted patriotic scenes; his twin brother was a renown freedom fighter. Wojciech’s portrait of Pilsudski is shown below.

Piłsudski on Horseback

Wojciech Kossak, 1928

oil on canvas, 43 x 36 in

National Museum, Warsaw

photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons, source http://artyzm.com/e_obraz.php?id=1616

Lancer Watering Horses

Jerzy Kossak, 1937

oil on cardboard

auctioned by Agra-Art, Warsaw, 2011

All rights to photo reserved by http://www.artvalue.com

Jerzy Kossak (1886-1955) , son of Wojciech, followed the family tradition of painting military scenes but was not as revered as his forebears. He served in the Polish army during the First World War, but we are unsure what he did during the Second.

We have no strong evidence that Powell was thinking about the Kossaks, but we do know that Michalski’s worries about the continued existence of his family’s work reflected what was actually happening in Poland during the war. The Germans occupying Poland were destroying or plundering not only ‘degenerate art‘ and Jewish art, but also any art that might remind the Poles of their national heritage. Some of Wojciech Kossak’s works were among the art that disappeared during the Nazi occupation.