At Sir Magnus’ dinner party, an entertainment is wanted.

Mona Lisa

Leonardo DaVinci, 1503-1506

oil on poplar wood

Louvre Museum

photo in public domain from Wikimedia.org via Galerie de tableaux en très haute définition

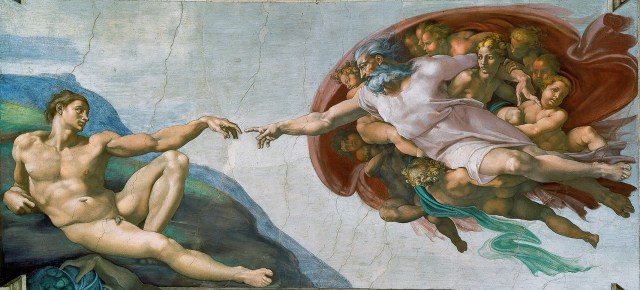

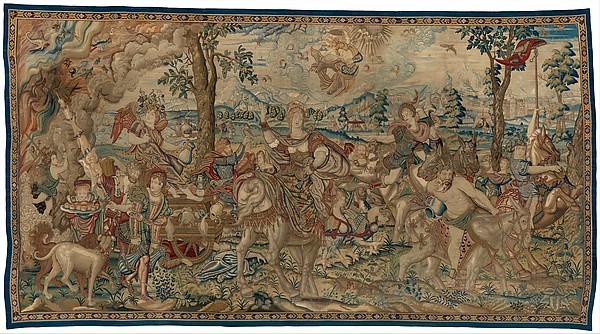

“‘Let’s pose some tableaux,” said Matilda. ‘Donners can photograph us in groups.’” Several themes are floated and discarded. “‘What about some mythological incident?’ said Moreland. ‘Andromeda chained to her rock, or the flaying of Marsyas?’ ‘Or famous pictures?’ said Anne Umfraville. ‘A man once told me I looked like Mona Lisa. I admit he’d drunk a lot of Martinis. We want something that will bring everyone in.’ ‘Rubens’s Rape of the Sabine Women,’ said Moreland, ‘or The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch. We might even be highbrows while we’re about it, and do Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. What’s against a little practical cubism?’” [TKO 126/124]

Rubens, Bosch and Picasso are likely to be familiar names to most readers of Dance, but Moreland’s particular suggestions from their oeuvres, seemingly chosen at random, are worth considering closely for the tone they set for the proceedings at Stourwater.

The Rape of the Sabine Women was a theme treated by many painters of the high Renaissance, Baroque, and neoclassical periods. It depicts an episode in the legendary founding of Rome, recounted by both Livy and Plutarch, when early Roman men abducted women from the Sabine tribe, indigenous to the Italic peninsula, in order to furnish themselves with wives and start populating their infant empire. Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665), painter of The Dance to the Music of Time, made two memorable depictions of the subject, of which the 1637-8 version, now in the Louvre, is reproduced here.

The Rape of the Sabine Women

Nicolas Poussin, 1637-8

oil on canvas,

Louvre Museum

photo in public domain from Wikimedia.org

But Peter Paul Rubens’ (1577-1640) rendition of the Rape, approximately contemporaneous with Poussin’s and now in the National Gallery, is the one suggested by Moreland for a tableau vivant. Rubens has depicted the Sabine women wearing (or tumbling out of) Baroque garb, so that his account has itself taken on the character of a tableau vivant, and the horror of the founding legend is thus somewhat ameliorated.

Rape of the Sabine Women

Peter Paul Rubens, 1635-7

oil on panel, 67 x 93 in

National Gallery, London

photo in public domain form Wikimedia.org via Web Gallery of Art

The story is still a source of cultural reference. Picasso painted a version of the scene in 1963, now owned by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. In 1937, Stephen Vincent Benet wrote a short-story parody of the theme entitled The Sobbin’ Women, which in turn furnished the material for the 1954 film and 1982 Broadway musical, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers,” in which all trace of the original brutality and tragedy of the motif has been eliminated. Upon reflection, Powell’s depiction of this period in Nick’s early adulthood, during which Sir Magnus, Templer, Moreland, Quiggin, Umfraville and the others swap and abduct each other’s women with alarming frequency and rapacity, comes itself to seem a kind of parody of The Rape of the Sabine Women, poised somewhere between the pathos of Rubens and the romantic humor of Seven Brides for Seven Brothers.

Heironymous Bosch (?-1516), the Netherlandish fantasist, painted the triptych now exhibited in the Prado as The Garden of Earthly Delights. What his intentions were in doing so have remained an academic controversy for the 500 years since he painted it. The left panel of the triptych shows Adam and Eve with Christ in the primal paradise. In the right panel countless souls suffer the torments of hell. In the center, Bosch envisions a panorama of human enterprise and diversion, which viewers may regard with delight and inspiration at the pleasures of our earthly home, or may view with trepidation for the fate of all who succumb to the earthly temptations on display. Either way, Bosch’s Garden is evocative of Stourwater and its guests, who find in its walls every imaginable luxury and opportunity for diversion, but also oubliettes and dark passages that lead to scenes of unspeakable practices.

The Garden of Earthly Delights

Hieronymous Bosch ~1490-1510

oil on oak panels, 88 x 175 in

The Prado, Madrid

photo in public domain from Wikimedia.org

Finally, Moreland’s witty nomination of Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon of 1907 suggests the intellectual elevation of the gathering, the licentious undercurrent notwithstanding. Moreland says the choice would be the “highbrow” one, even though the Picasso painting hasn’t a shred of literary, historical or religious content to it. It shows only five nude women, prostitutes in a brothel it is generally agreed.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon

Pablo Picasso, 1907

oil on canvas, 98 x 93 in

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

photo in public domain in US from Wikipedia.org but under copyright in France

What makes Moreland’s choice interesting here, as well as funny (“a little practical cubism”), is how Moreland’s use of the term “highbrow” alerts us to the huge intellectual dislocation Picasso’s 1907 painting was still making in the 1920s. Together with Georges Braque, Picasso had managed to turn the attention of viewers from the content of the image to the question of how images are meant to work. A century later we have all learned to use the language of Cubism in images everywhere, but during the first decades after the appearance of Demoiselles d’Avignon it was still the challenge of “highbrows” to master that lexicon.