On first meeting Hugh Moreland, Nick describes his physical appearance: “Moreland, like myself, was then in his early twenties. He was formed physically in a ‘musical’ mold, classical in type, with a massive, Beethoven-shaped head, high forehead, temples swelling outwards, eyes and nose somehow bunched together in a way to make him glare at times like a High Court judge about to pass sentence. On the other hand, his short, dark, curly hair recalled a dissipated cherub, a less aggressive, more intellectual version of Folly in Bronzino’s picture, rubicund and mischievous, as he threatens with a fusillade of rose petals the embrace of Venus and Cupid, while Time in the background, whiskered like the Emperor Franz-Josef, looms behind a blue curtain as if evasively vacating the bathroom.” [CCR 21/16]

Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time

Agnolo Bronzino ~1545

oil on wood 57 x 46 in

National Gallery, London

photo public domain from Wikimedia Commons

The painting in question is commonly known as Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time and its painter, Agnolo di Cosimo, is commonly known as Il Bronzino. Powell’s explication of its narrative content is certainly the funniest, but only one of hundreds lavished upon this engaging and enigmatic painting in the National Gallery of London. Bronzino (1503-1572) was a Florentine painter, the protege of and later collaborator with Pontormo, and a disciple of Michelangelo. Bronzino is virtually the paragon of Italian Mannerism, a term used to characterize the evolution of High Renaissance naturalism into a visual language of distortion in the service of expression. Michelangelo is sometimes described as a Mannerist, but his distortions generate deep wells of genuine feeling in his works. Bronzino, by contrast, exhibits a technical mastery of illusionism that perhaps has never been equalled, but his glorious surfaces always remain just surfaces. His Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time has some narration or other about it, but the impression it leaves is that of Bronzino having fun with flesh. Powell’s droll remark about Time vacating the bathroom calls our attention to Bronzino’s exquisite, vacant genius.

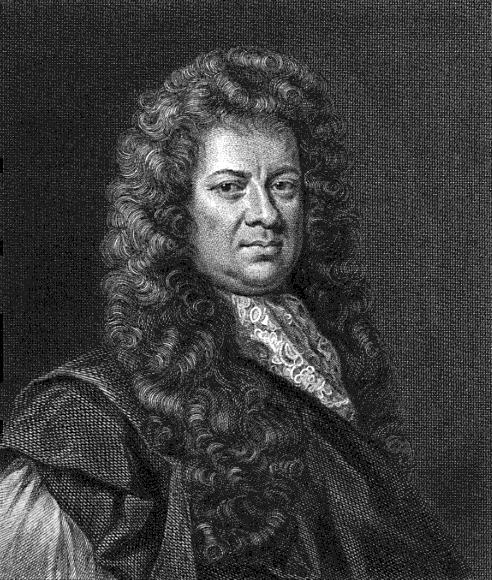

Constant Lambert as a Christ’s Hospital Schoolboy

George Washington Lambert, 1916

oil on canvas 50 x 37 in

Christ’s Hospital Foundation

photo copyright Christ’s Hospital Foundation from BBC Your Paintings

In TKBR Powell gives more evidence of the similarities between his friend Constant Lambert and Hugh Moreland. Powell writes that the painter George Washington Lambert, Constant’s father, was a great admirer of Bronzino and painting his son at age 11, “managed to impose a distinctly Bronzino type of looks…” [TKBR 144-145]